Thomas Cook's Death Is Pure Ernest Hemingway

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In May 2018 Thomas Cook Group Plc’s shares traded as high as 146p, its 2023 bonds yielded a modest 3.5% and analysts were mostly very positive about its prospects. So how did the company go bust barely 16 months later and who’s to blame? To borrow a phrase from Ernest Hemingway, Thomas Cook went bankrupt gradually, then suddenly.

The demise was caused by rapidly changing consumer habits, combined with a capital structure and financial reporting that were less than optimal. A sharp drop in demand during Europe’s summer heatwaves in 2018 put the company on a downward trajectory that it was unable to pull out of.

The past year’s troubles weren’t the first to engulf the 178-year-old group. Six years ago it came close to collapse, and its rescue saddled it with a large debt that was hard to shift.

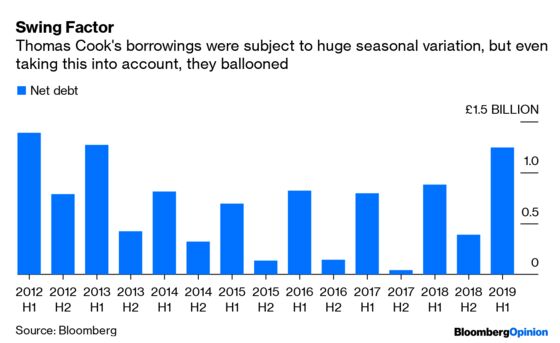

Yet over the subsequent five years the company was able to better manage its working capital. In 2016 it reinstated its dividend. A year later net debt was just 40 million pounds ($50 million).

In hindsight, this rehabilitation was as superficial as a snapshot from a sunny beach. Thomas Cook’s finances were still too fragile for a company that was struggling with the shift of holiday booking to the internet; and one that was also subject to the cyclical swings of consumer confidence.

The shortcomings were laid bare after holiday bookings fell in 2018. Unlike its German rival Tui AG, Thomas Cook didn’t have strong hotel and cruise brands to help it cope. The British company parted ways with its then finance director after just nine months in the job.

By March this year net debt had ballooned to 1.25 billion pounds — that’s too much for a company that generates little cash flow and has huge seasonal variations in the amount of money going in and out of the business. Stuart Gordon of Berenberg, one of the few financial analysts to get it right on Thomas Cook, estimates that there’s a 1 billion pound swing in working capital requirements between the end of September and the end of December.

Unlike some recent British corporate failures such as Carillion, BHS and Patisserie Valerie, Thomas Cook’s auditors Ernst & Young seem to have been on the ball (at least toward the end). In the last annual report they called attention to the company’s worrying habit of classifying costs as exceptional whenever possible.

Even after this, like so many companies in trouble, it had a troubling lack of hard assets (the kind of stuff you can sell in a crisis), with the biggest element of its balance sheet made up of intangibles including goodwill. In hindsight, the management’s biggest mistake was not strengthening that balance sheet by raising fresh capital when they had the chance.

As recently as February management was still blind to the dangers, though, telling analysts it was wrong to compare Thomas Cook’s predicament to its 2012 troubles. As conditions worsened and the share price collapsed, raising equity became impossible. The slump in the bonds made issuing fresh debt expensive too.

Thomas Cook did put its airline up for sale. Yet it acknowledged a few months later that its ability to continue as a “going concern” would be in “significant doubt” if the disposal didn’t happen. Statements like these are a killer for consumer-facing businesses. Customers naturally won’t book holidays with an operator that can’t guarantee it can keep going. Credit card companies respond by holding a bigger reserve of the cash from ticket sales in case the company goes bust (because customers will then claim a refund). And suppliers tighten credit terms. All of this makes an already bad cash situation even worse.

That probably contributed to Thomas Cook’s financing needs ballooning from 300 million pounds in May to 900 million pounds in August, which was meant to be addressed by a hefty debt-for-equity swap in the coming weeks. Instead, lenders such as Royal Bank of Scotland Group Plc demanded another 200 million pound backup facility. A slow death became a rapid one.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andrea Felsted is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the consumer and retail industries. She previously worked at the Financial Times.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies. He previously worked for the Financial Times.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.