There’s an Easter Egg in This Column. Can You Find It?

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Just before Easter, the Bank of England revealed the design of its latest £50 note, the reverse of which features a portrait of the code-breaker and computing pioneer Alan Turing.

In addition to the standard security features (holographic patches, foil ornaments, ultraviolet text, etc.) the note includes a slew of references to Turing’s life and work, including: a ticker tape of his birth date in binary code; sunflower spirals relating to his morphogenetic research; and technical drawings for the British Bombe that helped crack the Nazi’s Enigma code.

Then, to promote the note, the bank enlisted the British intelligence agency GCHQ to incorporate these “geeky Easter Eggs” into a “seven-hour” hunt — “our most difficult puzzle ever.”

What, you may well ask, is going on?

* * *

Easter egg hunts are said to date to sixteenth-century Lutheran custom and — like many “traditions” from tartan to Christmas trees — were popularized by Queen Victoria. However, our modern, secular and technical idea of such hunts dates to the dawn of popular computing and, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, was first codified in 1986:

“Re: Few More Option-keys Tips in net.micro.mac (Usenet newsgroup) 25 Apr. Why not have a periodically updated list of these option, command, and other combination Easter egg type-of-things?”

In this context, Easter eggs are:

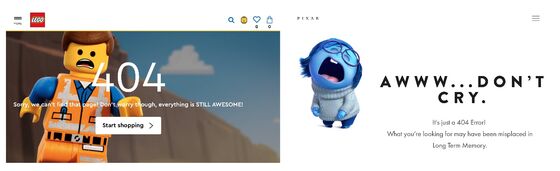

“An unexpected or undocumented message or feature hidden in a piece of software, intended as a joke or bonus. Also: a feature of this kind in film, music, and other forms of information or entertainment.”

In the age of the internet, it’s almost impossible for Easter eggs to remain hidden for long. Indeed a cottage industry is now dedicated to documenting hidden features the moment they are found. Curiously, this mayfly shelf-life has not deterred Easter egg creators: Bonus features now appear across every sphere of endeavor, earthbound and extraterrestrial.

When in February the parachute of NASA’s Perseverance rover unfurled over Mars’s Jezero Crater, it revealed two binary code messages enciphered in the fabric’s multicolored pattern: the GPS coordinates for NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, and a reference to Theodore Roosevelt’s 1899 “Strenuous Life” speech — the exhortation, “DARE MIGHTY THINGS.”

Even landing on the Red Planet, it seems, demands a little secret pizazz.

* * *

The industry most associated with Easter eggs (confectionary aside) is computing — and hidden in games, applications and operating systems is an ever-expanding catalogue of curiosities. Most are relatively picayune jokes, but a few are decidedly non-trivial efforts — from the secret space simulator in Microsoft Office 97 (accessed via the Excel cell “X97:L97”) to the software son et lumière in the Tesla X:

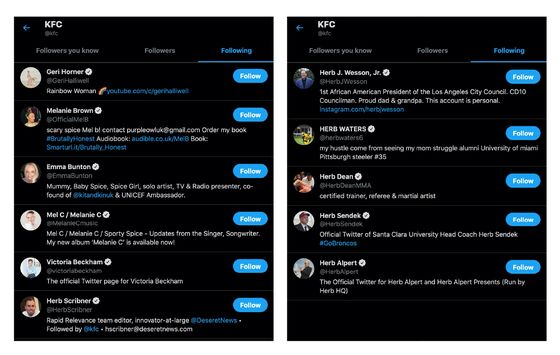

One of the most committed Easter egg concealers is Google, which has incorporated a panoply of search gags both frivolous (“askew,” “loneliest number,” “define anagram”) and technical (“emacs,” “recursion,” “