The World Economy Can Get By Surprisingly Well With $129 Crude

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Markets have a short memory.

It’s hardly surprising that when the price of Brent crude jumps 39% over the course of a month, people take fright. Russia usually sits ahead of Saudi Arabia these days as the world’s biggest oil producer after the U.S. The position of its exports on global markets looks highly uncertain, since sanctions that were designed to exempt energy trade appear to be spooking other parts of the supply chain — from shipping to finance to maintenance — that are essential to keeping the petroleum flowing.

Many players are already putting a precautionary stop to their oil purchases from Russia. Those that haven’t may now think twice, after Shell Plc’s purchase of a cargo of crude was criticized by Ukraine’s foreign minister Dmytro Kuleba as smelling of “Ukrainian blood.”

In a market where West Texas Intermediate crude averaged about $51 a barrel for six solid years from the start of 2015 to the end of 2020 and dipped as low as minus $40 less than two years ago, current trading north of $130 seems like the start of the apocalypse. In truth, it’s very nearly a return to normal. For the previous five years from the start of 2010, the price averaged $92 — or about $119 at the start of that period, after adjusting for inflation using the U.S. consumer price index. War and sanctions the like of which the world has rarely seen in decades are only driving petroleum to levels that would have seemed routine a decade ago.

Those weren’t a bad time for the global economy. Both 2010 and 2011, when crude prices recovered from the slump of the 2008 financial crisis to hit the pace they maintained until midway through 2014, were two of the strongest years for growth since the mid-2000s. To be sure, that was helped by the fact that prices were being driven higher by the strength of demand, rather than a dearth of supply. Still, the link between high oil prices and global recessions in general is weaker than you might think.

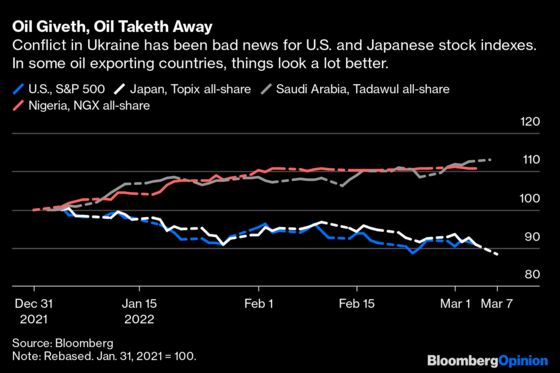

For one thing, one country’s extortionate expense is another country’s lavish profit. Emerging economies tend to perform better than rich ones when oil prices rise, probably because for many of them a large share of exports and GDP has traditionally come from hydrocarbons. All-share stock indexes in Saudi Arabia and Nigeria are both up more than 10% so far this year, roughly the same amount that share markets in wealthier nations like the U.S. and Japan have declined.

Even if you restrict your horizon just to richer nations, the connection is surprisingly weak. It makes intuitive sense, to be sure, that a rise in crude prices should translate directly into a slowdown in economic activity, because energy for most of us is a non-discretionary item. If we’re spending more filling up our gas tank or paying our utility bills, we’ll have to make savings in other parts of our household budgets, such as buying clothes.

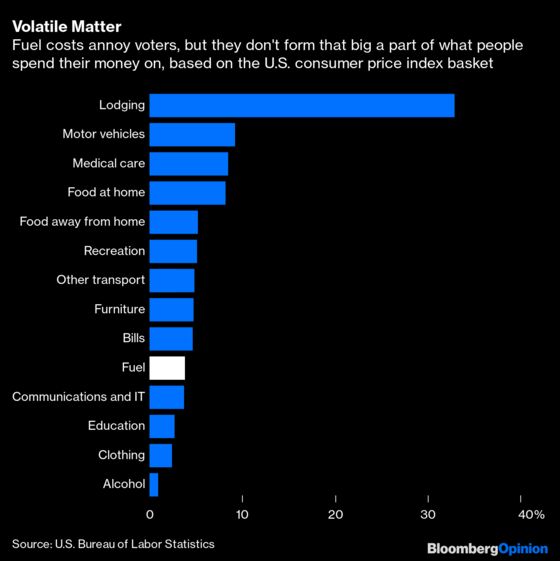

The problem with this theory is that petroleum just doesn’t constitute such a large share of most people’s spending any more. In the basket of goods from which the U.S. consumer price index is constructed, it accounts for just 3.7%, rising to 5% for blue-collar workers. That’s about the same level as restaurant meals, furniture, or utility bills, and far less than medical care, auto sales, or food at home. Voters unquestionably notice a sharp rise in prices at the pump. The economy, however, is often spared.

Why have crude price spikes so often led to economic decline, then? One theory put forward in an influential 1997 paper co-authored by future U.S. Federal Reserve Governor Ben Bernanke is that it’s not the price of crude itself, but the way the central bank responds to those prices. A central bank with a fanatical inflation-fighting focus will take rising energy prices as a cue to raise interest rates, which will squeeze the economy in general as well, including a far more important part of the spending basket: housing costs.

To take the sting out of an oil shock, officials need to just sit back and wait for the crude market to rebalance. That’s in practice what they do when they focus on core inflation so as to strip out the effect of more volatile food and energy prices. Raising interest rates to stamp out high energy prices is like bleeding a patient to calm a fever.

Bernanke had an opportunity to put his ideas into practice a decade later, when crude prices rose to a record while he was in charge of the U.S. central bank. While a recession did indeed follow within months of oil’s spike in July 2008, few economists now argue there was a strong connection between the two.

That’s reason to worry less about the price of oil, and more about all the other things happening in the world economy. Most recessions follow an oil price spike, but it’s much less common for oil price spikes to lead to a recession. The global economy can still ride out this turmoil.

More From Bloomberg Opinion:

- Thirteen Minutes That Showed OPEC+’s Irrelevance: Julian Lee

- We Already Have a Solution for Oil's Price Shock: David Fickling

- The Bond Market Sees a Recession In Oil Shock: Lisa Abramowicz

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.