There’s a Shade of Evergrande in the U.K. Energy Crisis

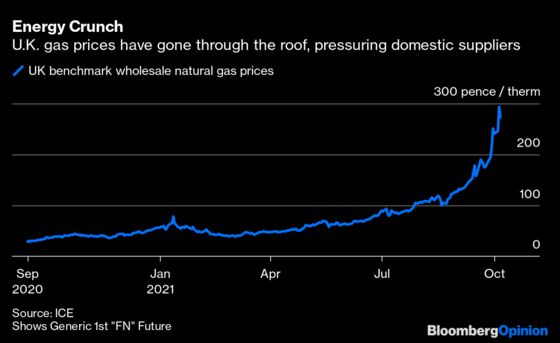

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Barely a week goes by without a U.K. electricity and gas supplier being toppled by soaring commodity prices. Millions of British customers face an unsettling wait to learn if their power provider will survive, who’ll take over their contract, and whether their energy bills will increase. Britain’s energy regulator Ofgem — the Office of Gas and Electricity Management — has written to those companies still standing demanding urgent information on their finances.

Alas, after studying some of their recent published accounts, I doubt the responses to Ofgem are reassuring. Even before energy prices skyrocketed, many suppliers were loss-making and had liabilities far in excess of their few assets.

To be sure, government-mandated price caps make life tough for energy retailers as they can’t easily adjust tariffs to reflect their costs. For small suppliers that want to fully protect themselves against commodity price swings, such hedging can be prohibitively expensive.

Yet the foundations of this extraordinary crisis were a lack of financial resiliency, light-touch regulation and unsustainable pricing practices that left the industry unprepared for its Black Swan moment. “Rising electricity and gas prices pushed suppliers over the edge but weren’t the root cause,” says Investec utilities analyst Martin Young.

This tale of inadequate capital buffers and “moral hazard” will be familiar to students of previous crises. And its resolution will be similar too: a bonfire of the energy suppliers, in which the small fry are consumed by better capitalized entities. Big suppliers will get even bigger.

Injecting more competition into a market once dominated by the “Big 6” energy companies like British Gas (owned by Centrica Plc) and EDF Energy (Electricite de France SA) was well intended and achieved some success. The market share of legacy suppliers has dropped to around 70% and new entrants helped spur innovations in clean-power tariffs, online services and smart-meters, aiding energy efficiency and the decarbonization drive. Providers were forced to become more efficient and, at least in some cases, customer service improved.

Well-funded entrants like Ovo Energy Ltd and Octopus Energy Ltd, which received a $600 million investment from Al Gore’s Generation Investment Management LLP last month, have achieved scale economies, in part by absorbing rivals. Ovo took over SSE Plc’s retail arm in 2019 while Octopus has taken on more than half a million customers from the failure of Avro Energy.

But because licenses and software were cheap to come by, there’s been a proliferation of less resilient players. At the peak in 2018, there were 70 companies supplying energy to British consumers. That number has since fallen to fewer than 40 and many more exits and failures are expected before winter’s end.

Perhaps there’s such a thing as too much competition.

The new entrants expanded rapidly because it was their best hope of generating cash. As we’ve seen in the airline industry and now with Chinese property developer Evergrande, getting customers to pay in advance is a cheap source of funding. The energy suppliers held up to 1.4 billion pounds ($1.9 billion) of excess customer cash, or around 65 pounds per household, Ofgem estimated in March, and they weren’t required to ringfence that money.

Another popular way to generate cash was to delay paying regulatory charges, in particular clean power subsidies called Renewables Obligations, which cost about 6 billion pounds annually. At a push, power suppliers were able to hold off settling 19 months worth of RO charges, delivering another cheap source of unsecured working capital.

Customers aren’t blameless here. Assisted by price comparison websites, they opted for the cheapest tariff, rather than prioritize the supplier’s financial resiliency. Under Britain’s “Supplier of Last resort” system, customer credit balances are protected if the provider collapses. So consumers couldn’t really lose. The cost of unhonored customer balances or Renewables Obligations is shared across the remaining energy suppliers, and ultimately all consumers’ bills.

“Responsible suppliers must either lose money to retain customers (and write loss-making business), or lose customers to retain margin,” Shell Energy complained last year. Indeed it’s easy to see how suppliers might decide to throw caution to the wind, knowing if they overreached, the costs would be “mutualized” (to use the industry jargon).

If power prices rocket or demand is higher than anticipated as happened during the last cold winter, things can quickly unravel. Documents from recent insolvency proceedings show how suppliers defaulted on credit facilities with power providers or other counter-parties.

Though it moved too slowly, Ofgem has already introduced measures to promote greater financial resiliency, increase financial monitoring and ensure those running energy suppliers are qualified. It’s considering forcing suppliers to make RO payments more frequently and to insist excess customer balances are refunded. But tightening the ratchet now could push even more companies over the edge.

“A race to the bottom ultimately hasn’t served consumers well. We need innovative, cost-efficient and financially stable suppliers,” says Investec’s Young. The survivors will be those who do more than just “sell cheap electrons and molecules,” he says.

Hopefully these diversified players will shoulder most of the burden of cleaning up this mess. However, the era of freewheeling competition is over and customer bills will go up.

As well as paying bills a month or more in advance, credit balances build up during the summer months when customer energy needs are lowest(yet they pay the same monthly amount). In theory these credit balances should fall back to zero during the winter heating period, but in reality they don’t always.

Around 189 million pounds of RO charges have been mutualized since 2018, Ofgem said in March,and 48 million pounds from credit balances. Suppliers often agree to cover at least part of the credit balance liabilitywhen they take over a failed supplier.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies. He previously worked for the Financial Times.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.