The Truth About Trump's Covid-19 Cocktail ‘Cure’

These drugs are promising, however, the U.S. president is exaggerating their benefit and likely availability.

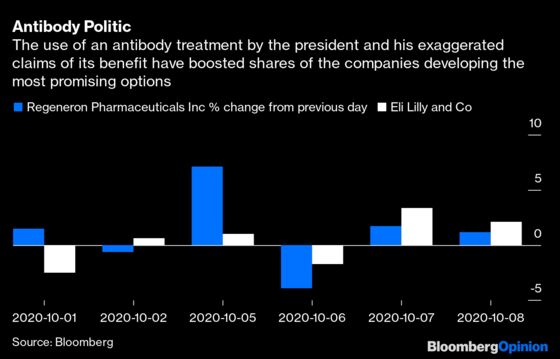

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- President Donald Trump is all-in on antibody treatments — medicines that can mimic the body’s response to infection, including Covid-19. After receiving an experimental dual-antibody cocktail from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. last week to treat the case of coronavirus he contracted, he is claiming that the drug and a similar medicine from Eli Lilly & Co. cure the disease and will soon be widely available to Americans for free. “I want to get for you what I got. And I’m going to make it free,” Trump told viewers in a video he tweeted. “It’s a cure.” The reality is more complicated.

These drugs are promising and may serve as a valuable bridge to vaccines. Both Regeneron and Lilly have requested emergency use authorizations of their medications based on small studies, and the Food and Drug Administration will face pressure to say yes. However, the president is exaggerating their benefit and likely availability. What’s more, his hype and rush to push antibodies out will make it harder to get the most out of them.

Antibodies aren’t a miracle cure responsible for the president’s recovery. As my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Faye Flam wrote earlier this week, Trump received so many other medicines, including the antiviral remdesivir and the powerful steroid dexamethasone, it’s impossible to tell which did what. Drawing conclusions from just the president’s experience is irresponsible.

We do know that medicines developed by Regeneron and Lilly reduce viral load early in a patient’s illness. There’s some evidence that this translates to reduced symptoms and fewer hospitalizations. But these preliminary conclusions are based on a limited number of patients who received different dose levels.

There are enough open questions that it's unclear whether the FDA should allow broad use of these drugs at all. The data we have so far comes only from patients with relatively mild disease treated outside of the hospital. Researchers are now testing the medicine on sicker hospitalized people, as well as for use as a short-term vaccine in those at high risk of infection. Prophylactic use is particularly promising because it may require a lower antibody dose. The lower the dose, the more people doctors can treat.

Releasing the drug early may derail or delay these crucial trials. Fewer people will be willing to enroll in studies that may give them a non-working placebo when the medicine is available, and limited supplies will be used quickly on what may be the wrong patients.

There are currently 50,000 treatment-level doses of Regeneron’s therapy available; the company hopes to have doses available for 300,000 patients within the next few months. Lilly expects to have 100,000 doses of its treatment this month and as many as a million by year’s end. But it will have only 50,000 doses of a more promising combination. (As a point of context, the U.S. is reporting nearly 40,000 new Covid-19 cases a day; at that rate, we can expect 1.2 million people infected in the coming month alone.)

The president’s promise of an imminent wide rollout will be hard to keep. The same goes for his pledge that the antibodies will be entirely free. Initial doses of Regeneron's treatment will be free to patients because taxpayers already shelled out $450 million through an “Operation Warp Speed” contract. There's no assurance on pricing after that initial batch. Lilly has signed no such agreement, and it remains unclear how it will price its therapy; it won't be free unless the government takes action.

With new stricter FDA guidelines seemingly ruling out a vaccine by Election Day, Trump appears to be trying to fill the void with these therapies instead. The rush means some may get treated sooner, but more may lose out in the long run.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Max Nisen is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering biotech, pharma and health care. He previously wrote about management and corporate strategy for Quartz and Business Insider.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.