(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Back in 2009, in the darkest days of the global financial crisis, the U.S. government embarked on a high-stakes effort to restore confidence. Its primary tool: stress tests of the country’s largest banks. The Federal Reserve estimated how much the institutions stood to lose, and the Treasury promised to provide whatever resources they needed. The exercise worked surprisingly well, and proved to be the turning point for the recovery.

Since then, stress tests have become standard procedure around the world, but with a different mission. Instead of shoring up the system, they seek to ensure that banks can weather a future crisis. It’s a role for which they are less well suited, and that threatens to create a false sense of security.

Stress tests help determine one of the most important numbers in the financial system: What percentage of banks’ funding must come in the form of capital. Also known as equity, capital has the advantage of absorbing losses automatically, making the whole system more resilient. Bank executives prefer to use less of it and more debt, for two reasons: The added leverage boosts profitability in good times, and debt comes with an array of government subsidies — including tax breaks, deposit insurance and access to emergency loans from central banks. To counteract the incentive to lever up, regulators establish and enforce capital requirements.

But how much capital is enough? Before the 2008 crisis, regulators had surprisingly little clue. They set a minimum — in the U.S., as low as $3 for each $100 in assets — and left banks to maintain a reasonable buffer above it. They assumed that a sense of self-preservation would get banks to the right level, and as late as 2008 insisted that it had. It hadn’t. Losses on subprime-mortgage and other investments overwhelmed banks, transforming the U.S. housing bust into a global disaster and undermining confidence in the entire financial establishment.

This is where the 2009 stress tests worked their magic. The Fed borrowed a tool that banks had been using internally and took it to a whole new level. Officials made a projection of how bad the crisis could get, and then used the Fed’s own models to estimate the capital injections each of the country’s 19 largest banks would require to get through. This independent assessment drew a line under losses, dispelling the uncertainty that was paralyzing markets. Meanwhile, the government backstop restored the confidence banks needed to raise capital from private investors.

Elsewhere, things went less well. In the European Union, national leaders couldn’t agree on a common government guarantee to recapitalize banks. The lack of a backstop left supervisors hesitant to subject banks to harsh scenarios, fearing that an honest reckoning would only deepen the crisis. As a result, Europe’s stress tests were much less effective. Some banks — such as the Franco-Belgian Dexia — required bailouts not long after passing. To this day, uncertainty about the extent of losses on non-performing loans weighs on the region’s financial sector.

Nonetheless, stress tests became a favored tool of regulators around the world — including in the U.S., the U.K., the euro area, Japan and Switzerland. Yet the peacetime exercise differs significantly from its crisis-fighting counterpart. Instead of projecting the outcome of an existing crisis, officials must come up with credible and adequately severe hypothetical scenarios — deep recessions, high unemployment, market routs. And instead of recapitalizing the whole system, regulators must single out poorly performing banks, restricting their ability to pay dividends or even requiring them to raise fresh equity.

The tests have struggled in their new role. One big issue is technical: Imitating a real crisis is really hard. To estimate losses, central-bank models must look to a history in which the government has almost always stepped in to rescue big banks, so they struggle to guess what would happen in the absence of such support. Also, the scenarios start with an economic and market shock that then affects banks, which is too simple: In a crisis, unexpected losses destabilize the financial system, which in turn hits the economy and rebounds back to banks in a vicious cycle, amplified by institutions’ simultaneous efforts to sell assets and cut losses. Attempts to model these complex interactions are still in their infancy.

Such shortcomings mean that it takes extremely harsh-looking scenarios to generate losses anywhere near what’s needed to challenge banks. Consider the 2018 U.S. stress test. It included a nearly 6-percentage-point increase in unemployment and a 65% drop in the stock market — both more severe than in the 2008 crisis. Yet estimated pre-tax losses for the four largest U.S. banks didn’t exceed 4% of assets. During the actual crisis, losses were as high as 6% of assets — and that’s with the benefit of government support.

Another problem is human nature. In 2009, the worst-case scenario was clear and present: No leap of imagination or feat of political will was required to recognize how bad things could get. But as the memory of the crisis fades, harsh scenarios start to look vanishingly improbable, and officials become more receptive to banks’ complaints that the tests are too tough or burdensome. This undermines what should be one of the tests’ main advantages: Their ability to lean against the financial cycle, becoming more stringent in good times to ensure banks build up more equity to survive the worst times.

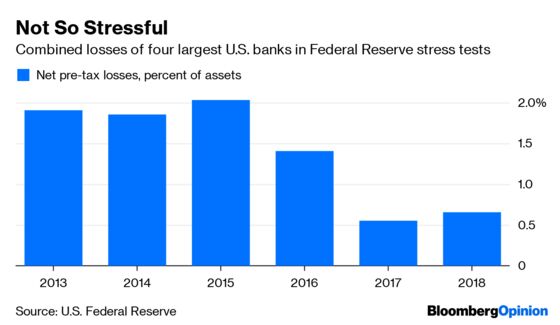

Again, the U.S. exercise offers an illustration. On the surface, the scenarios appear to be getting tougher over the years. But they keep generating smaller pre-tax losses: Net of income, losses amounted to a weighted average of just 0.7% of assets for the four largest banks in the 2018 tests, down from 1.9% in the 2013 tests.

Granted, the tests do have benefits. They push banks to improve their risk management, making executives think harder about worst-case scenarios and get a better grip on exposures across their far-flung units. They can ensure that capital requirements keep pace with changing markets, by challenging banks’ internal models and focusing attention on new kinds of threats. They provide at least some constraint, preventing capital from falling too far.

Now the Fed is moving to undermine even those advantages. It has largely eliminated the “qualitative objection,” which allowed officials to flunk institutions that couldn’t demonstrate an adequate grasp of the risks they faced. It has released details of the model it uses to estimate losses, similar to showing banks the exam before they take it. And it intends to share the test results before banks decide on their plans for dividends and stock buybacks, allowing them to avoid the embarrassment of having their plans publicly rejected.

Taken together, the Fed’s changes sharply reduce banks’ incentives to think for themselves. Instead of seeking the best way to make their own projections, they can wait for officials to tell them how much money they can pay out to shareholders, and how much they must keep in the business as capital. As a result, the whole assessment of the financial system’s resilience will depend more on the Fed’s stress-testing model, rather than on the interaction of many models. This lack of diversity increases the chances of missing important risks.

Worse, the Fed’s new head of bank supervision, Randal Quarles, wants to remove a crucial constraint: The requirement that banks survive the stress tests without falling below a simple ratio of equity to assets. Known as the leverage ratio, it was designed to act as a check on the usual regulatory capital ratios, which place minimal or even zero weight on assets believed to be safe. Without it, banks could theoretically pass the tests with almost no equity at all.

Ultimately, the best test of the stress tests is whether they require a level of capital that, by other measures, seems prudent. They don’t. On average, the six largest U.S. banks have less than $7 in capital for each $100 in assets — a leverage ratio of less than 7%. The top five euro area banks average less than 5%. The experience of the crisis and research by economists at the Minneapolis Fed suggest that’s not even half what would be needed to avert future bailouts.

In principle, a future administration could make the tests tougher. But the experience of the past decade suggests that fundamental flaws will persist. Statistical modeling might never be able to capture the full impact of a real crisis. And the process is perennially vulnerable to subtle degradation. As Dan Tarullo, who oversaw bank regulation at the Fed until April 2017, put it in a recent speech, stress testing is a “complicated way to set capital requirements — that’s one reason why it is peculiarly susceptible to being weakened without much fanfare.”

A better and much simpler approach would be to set capital requirements a lot higher in the first place. This would render regular stress tests unnecessary: Well-capitalized institutions wouldn’t come anywhere near failing. Authorities could free banks of the recurring cost and burden, and use the tests only where they have proven most useful — to restore confidence in actual crises.

As things stand, passing a stress test shouldn’t be seen as certifying that a bank is safe. And it’s dangerous if investors and officials think it does, because they’ll stop demanding more equity and allow standards to erode even further. As a result, one of the past decade’s biggest innovations in financial supervision could help bring about the crisis it was supposed to prevent.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Clive Crook at ccrook5@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Mark Whitehouse writes editorials on global economics and finance for Bloomberg Opinion. He covered economics for the Wall Street Journal and served as deputy bureau chief in London. He was founding managing editor of Vedomosti, a Russian-language business daily.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.