(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Jasmin Bedria, a personal trainer and nutritionist from Ormond Beach, Florida, visited her first Trader Joe’s in Maryland eight years ago.

“I walked in and it was just everything, from the atmosphere to the prices,” she recalls. “I could not believe we did not have one.”

The next day she started a Facebook page calling for the company to open a branch in the area around Ormond and nearby Daytona Beach. Today, her campaign has more than 4,000 supporters.

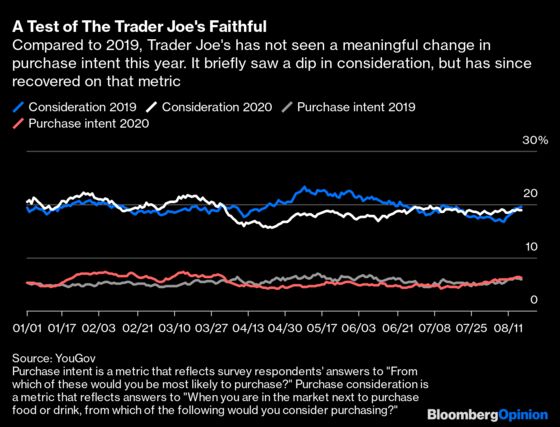

Bedria’s experience underlines the fanatical following that Trader Joe’s inspires. Even recent criticism — over the company’s initial handling of the Covid-19 crisis and product names consumers said evoked racial stereotypes — hasn’t done much to damage the brand.

But that doesn’t mean the 53-year-old retailer is in the clear. In fact, its future is more uncertain than ever, as it contends with changing shopping habits precipitated by the pandemic.

Trader Joe’s began life in 1967, when Joseph Coulombe (who died earlier this year) opened the first store in Pasadena, California, offering affordable wine and specialty foods.

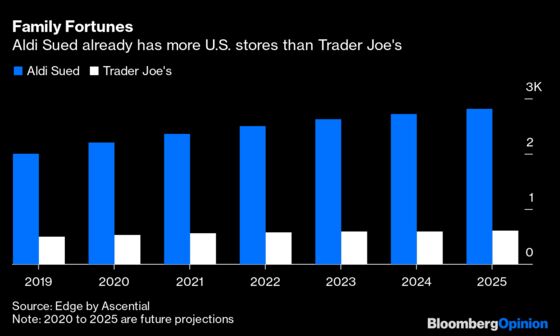

In 1979, Theo Albrecht — one of the two German brothers behind the Aldi empire — acquired the chain. In the early 1960s, after disagreeing on strategy, the brothers split Aldi. Theo took north of what has been dubbed the “Aldi equator” through the center of Germany, in the form of Aldi Nord, while Karl took the south through Aldi Sued.

Trader Joe’s continues to be owned by one of the three family trusts that control Aldi Nord, although it’s run as a separate company. The Aldi Sued branch trades as Aldi in the U.S.

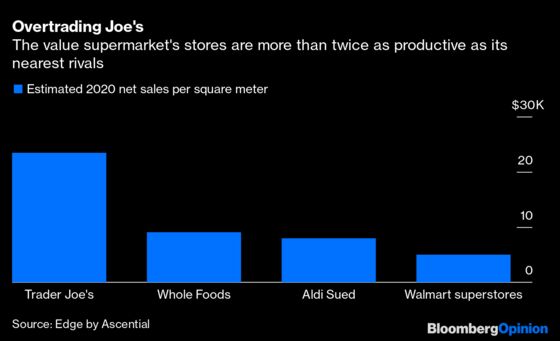

With its epicurean products, hand-written price labels and friendly staff sporting Hawaiian shirts, Trader Joe’s is a world away from its more austere cousin. Yet it shares many characteristics with the German discounters, and these have helped make it, on one measure, the most profitable supermarket in America.

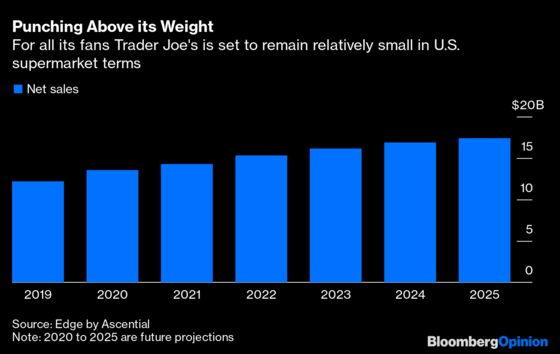

Trader Joe’s stocks less than 4,500 products. That’s more than would be found in a German discounter, but only about 10% of what’s carried by the grocery retailer Kroger Co. This limited product range, along with lower prices, generates high sales volumes. What’s more, about 85% of its products are private label — another discount trait — which have higher profit margins. All of this adds up to sales per square meter — a proxy for profitability — more than twice the industry average.

But Trader Joe’s currently faces two big challenges.

The first is that Covid-19 has driven a surge in online grocery shopping, and the company doesn’t sell via the internet. In its weekly podcast, “Inside Trader Joe’s,” the company said it would rather invest in its staff than in digital infrastructure.

Yes, going online would be tricky. Having employees fulfill online orders would swell the number of people inside stores, and translating the company’s high-quality service to home delivery would be costly.

But Trader Joe’s should experiment. Aldi Sued is taking its first steps in this direction, teaming up with grocery-delivery company Instacart in the U.S. and also offering curbside pickup. Using an intermediary would be a good way for Trader Joe’s to dip its toe in the water too.

If the company won’t be adding any sales via online orders, it will have to figure out how to maintain its industry-leading productivity.

However, fear of infection has pushed many consumers to embrace one-stop shopping, where they consolidate spending into fewer trips out. This trend favors big-box stores, such as Walmart Inc. and Target Corp., that carry far more household essential items. It’s bad news for any limited-service grocer.

The chain’s small floor plan — each location is typically 10,000 to 15,000 square feet — is also a pandemic-era challenge. In order to adhere to social distancing guidelines, the stores are limiting the number of shoppers allowed inside at a given time. This is a problem for all value retailers, which rely on a high number of relatively low-value transactions.

As the economic consequences of the pandemic grow heavier, consumers may be prepared to give up some of the comfort of shopping in a big store in exchange for lower prices. That would bode well for Trader Joe’s, as its products are estimated to be about 10-15% cheaper than comparable ones at traditional supermarkets. (Its bananas, sold individually, are famously low-priced at 19 cents each.)

In the meantime, the company could focus on getting shoppers to buy and spend more by finessing its product range. It could start selling diapers, for example. Merchandising and marketing efforts could also help. The company could show you how to make a whole week’s worth of lunches from its frozen foods.

But perhaps the best defense is to double down on what makes many consumers love the brand: In other words, just be more Trader Joe’s.

Mark Gardiner, who wrote the book, “Build a Brand like Trader Joe’s,” points to the “fun factor” of shopping there, including its quirky vibe, convivial staff and seasonal products. Enhancing these elements should encourage consumers to keep coming back, even when they’re faced with more choice elsewhere.

Jasmin Bedria believes a store in her Florida neighborhood would do “wonderfully,” despite the changes in shopping habits wrought by the pandemic. It looks like her wish may soon be granted. She was told earlier this year that the area around Ormond and Daytona Beach is on the company’s radar at last.

The company has since responded that it put in place measures to protect staff and customers, and it has denied that product names are racist.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andrea Felsted is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the consumer and retail industries. She previously worked at the Financial Times.

Sarah Halzack is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the consumer and retail industries. She was previously a national retail reporter for the Washington Post.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.