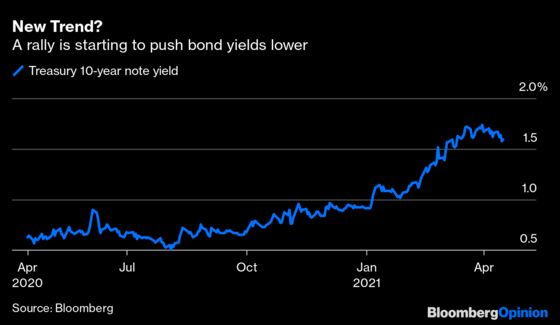

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In a week when the inflation rate jumped by the most since 2009 and retail sales posted one of their biggest monthly gains on record by surging 9.8% for March, the bond market predictably … posted on of its biggest rallies of the past year? Anyone with a passing knowledge of financial markets knows this isn’t supposed to happen. Bonds, specifically U.S. Treasuries, are what you sell when the economic outlook weakens. So with the economy booming by all measures, what gives? The answer may lie in the concept of perverse incentives.

The nature of markets is that it’s almost impossible to boil moves down to one explanation. The one that seemed to gain the most traction this week was that the rebound was simply a function of those who were bearish and called the big first-quarter selloff correctly deciding it was time to cash in their bets. This is the old “profit taking” explanation. But that’s not very satisfying. After all, why would an investor abandon a winning bet if all signs pointed to the wager continuing to work? Isn’t the consensus outlook for economic growth and inflation this year detrimental for safe, stodgy fixed-income assets?

To understand what happened this week — and what it means going forward — one needs to go beneath the headlines trumpeting broad economic strength. My Bloomberg Opinion colleague Brian Chappatta explained how the move in bonds makes perfect sense when you consider that it may prod the Federal Reserve to cut back on its massive bond purchase program sooner than forecast. He points out that bonds rallied every time that happened over the past decade or so because the economy invariably faltered without this extra stimulus.

The logical question is whether the trillions of dollars of fiscal stimulus deployed by the government has shored up the economy enough to prevent it from faltering again if and when the Fed decides to cut back on its quantitative easing measures. How much money are we talking about? One measure of the U.S. money supply has increased $2.62 trillion over the past 12 months to $19.7 trillion. The strategists at Deutsche Bank AG figure the amount of stimulus is bigger than even President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal on a per capita basis in today’s dollars.

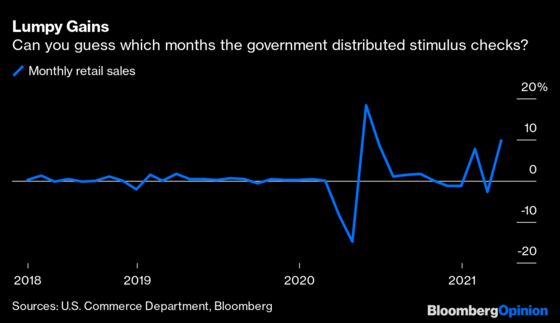

At first glance, the retail sales report issued by the Commerce Department can’t be described as anything but exceedingly strong. The 9.8% jump in the value of overall sales compares with the monthly average of 0.5% in the five years before the pandemic started in early 2020. The problem is that spending has become “lumpy,” showing big gains when the government hands out stimulus checks before falling back again.

So while Americans have been taken care of by the government, with Bloomberg Economics calculating $1.8 trillion in extra savings relative to pre-pandemic levels after three rounds of stimulus payments totaling about $880 billion, they are being selective on their spending. That’s hardly a sign of the “animal spirits” that are supposed to underpin what is forecast to be the strongest annual economic growth since the early 1980s.

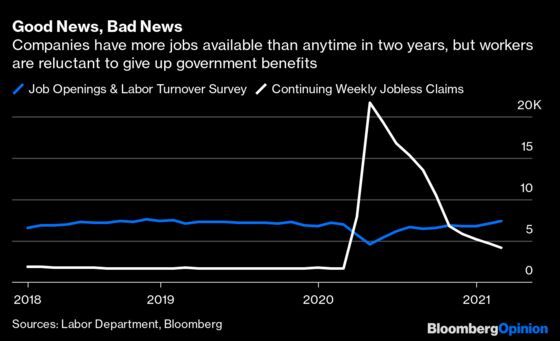

Clues as to why can be found in the Fed’s latest Beige Book, released on Wednesday. Even though the report, gleaned from the 12 regional Fed banks through April 5, upgraded the view of the economy by saying “national economic activity accelerated to a moderate pace from late February to early April,” there were numerous anecdotes of businesses that were unable to find workers, even by offering signing bonuses for hotel housekeepers and restaurant employees. Here is a sampling:

- Atlanta: “Employers noted that unemployment insurance benefits have made it hard to attract workers for temporary and low-wage positions.”

- Chicago: “Employers, temp agencies, and workforce development organizations pointed to a number of factors limiting labor supply,” including “financial support from the government.”

- Minneapolis: “Numerous contacts reported concern over the potential labor dampening effects of renewed enhanced unemployment insurance benefits.”

- St. Louis: “Hiring firms continued to compete for workers, who remain scarce; one employer reported the response rate among applicants offered an interview was as low as 50%.”

Bleakley Financial Group Chief Investment Officer Peter Boockvar summed it up nicely in a research note to clients this week, writing that “I keep coming back to the challenge of competing with the added government jobless benefits as a main factor. With the extra $300 per week, many are making the equivalent of $17.50 an hour assuming a 40-hour workweek.”

The problem for the economy may be that there’s too much fiscal support if it means Americans have a perverse incentive to collect money from the government rather than seeking gainful employment. How else can you reconcile the fact that the Labor Department said on April 6 that job openings rose to a two-year high of 7.37 million in February but continuing weekly unemployment claims stand at 3.73 million, more than double their pre-pandemic levels.

The risk all along for the bond market has been that employment recovers close to pre-pandemic levels, resulting in big wage gains that spark faster inflation. That may still happen, but the latest data seem to have tempered those concerns as evidenced by inflation-adjusted yields turning negative again for longer-term bonds. That’s not what you would expect to see if traders anticipated a secular turn higher in inflation anytime soon.

There’s no question the economy is on firm footing and will show heady growth this year thanks to unprecedented fiscal and monetary stimulus. Just don’t dismiss the idea that such growth may prove fleeting if a large percentage of Americans continue to decide that it makes more sense to collect a government check than enter the workforce.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Robert Burgess is the Executive Editor for Bloomberg Opinion. He is the former global Executive Editor in charge of financial markets for Bloomberg News. As managing editor, he led the company’s news coverage of credit markets during the global financial crisis.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.