(Bloomberg Opinion) -- When panic strikes financial markets and everyone runs for the exits, someone has to put up the cash — usually it’s governments and central banks. Indeed, the U.S. Federal Reserve has again and again intervened to calm nerves and keep markets moving by buying up Treasury bonds and injecting liquidity.

But as regulators move to fix more problems and reduce systemic risks, it is the massive Treasury market that faces further strains.

After the 2008 crisis, regulators forced banks to cut risk and hold more assets that are easily sold as a way to reduce failures in future panics. While that made banks more stable, other parts of the financial system have become vulnerable: Mainly, investment funds. Now, the regulators are trying to fix the funds, too. On Monday, the Bank for International Settlements, known as the central bankers’ central bank, said it wants funds to build up bigger war chests of liquid assets, too.

The problem is that the first place people run to during panics — and there will always be panics — is the U.S. Treasury market. It’s the biggest in the world. Since the global financial crisis, investors around the world have become increasingly reliant on it for liquidity and that has been causing problems. At the end of 2007, there were just $6 trillion in outstanding Treasury bonds; today, it’s $22 trillion. “The truth is that the Treasury market has grown too large for the existing infrastructure to handle,” says Mark Cabana, head of U.S. rates strategy at Bank of America Corp. Has it become too big to trade?

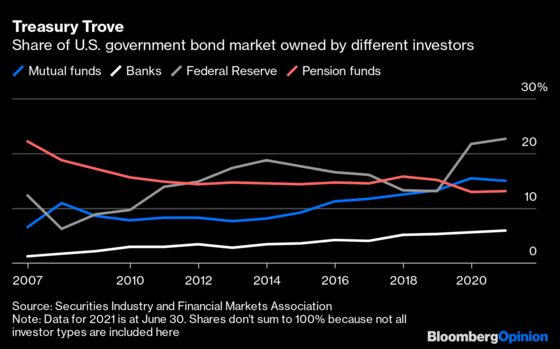

Any strain in trading Treasuries is worrisome because they are connected to every other financial market. They are often the first securities many funds sell when they need to raise cash quickly. As hedge funds and mutual funds have grown to play a more dominant role in financing the economy, they have bought up a greater share of Treasuries to use when they need liquidity. The BIS’s push to get funds to hold more liquid assets will increase everyone’s reliance on Treasuries.

The onset of Covid showed how the Treasury market can suffer stress. Normally when bad things happen in the economy, people sell riskier assets like stocks or corporate bonds and they buy Treasuries as a safe place to keep their money. But when Covid hit, investors sold whatever they could in their dash for cash, including Treasuries. In March 2020, the value of stocks fell, as did corporate bonds fell and Treasuries.

Even worse, parts of the Treasury market stopped trading as the banks and market makers who dealt the securities pulled back from their role of helping investors buy and sell. The prices of Treasuries and closely related derivatives diverged in surprising ways, according to a report last month by staff at the Federal Reserve, Treasury Department and other agencies.

It was far from the only recent spell of dysfunctional trading. The past few months have seen more volatility and failed trades. Even before the pandemic, in September 2019, there was a wild spike in the costs related to borrowing and lending Treasuries. Bankers and investors worry that these problems are going to get worse as the Fed tapers the bond-buying program it’s been using to stimulate the economy and more Treasuries move back into the markets.

The problem isn’t just the ballooning pile of government debt. Dealer banks and market makers lack flexibility to respond to surges in trading demand. These surges have become bigger and more common in the Treasury market because more and more investors use it as their first line of defense against liquidity shocks, according to Harvard economics professor Jeremy Stein, speaking at a recent Treasury market conference.

Banks are less flexible in the role of bond dealers because of regulations imposed since the 2008 crisis. The Supplementary Leverage Ration (SLR), designed to limit the size of bank balance sheets, has left them unwilling to significantly increase their own volume of trading, especially when there are lots of investors wanting to sell. This is because intermediating higher volumes of trades means holding larger inventories of bonds and growing their balance sheets. So either they need more capital, or they have to get rid of other, higher earning assets, like loans.

When banks don’t respond to the demand for higher trading volumes, investors struggle to buy or sell bonds and prices become more volatile. One of the Fed’s moves to ease market problems after the pandemic broke out last year was to temporarily exclude Treasuries from the SLR so that banks could handle more trading. Some banks want the suspension made permanent, but the Fed isn’t likely to agree to that.

Another reason market-making is less flexible is the rise of high-speed electronic trading firms. These run a low-risk business model where they aim to keep very little risk on their balance sheets. That means they only trade when they can be sure of both buying and selling. When markets get wild, they disappear from the scene.

There are reforms in the works that might help. One is to create some kind of platform where investors of all kinds can trade directly with each other rather than relying on market makers to stand between them. That will help the market some of the time — but not when there are a lot more sellers than buyers.

Ultimately, only the Fed is big enough to settle everyone down. And while it has been quick to respond to recent crises, bankers and others want a permanent and reliable route to get cash from the Fed at all times. If the option is always there, the market should never malfunction, they believe. The U.S. central bank is partly on board: This year it is creating a new standing facility where banks will always be able to swap Treasuries for cash.

But that won’t fully solve the underlying problem because investment funds — and everyone else — will only be able to access Fed cash through a bank. And while the SLR remains unchanged, banks won’t be prepared to help very much because it means expanding their balance sheets. The facility needs to be opened up to investors and other trading firms to really work, said Donald Kohn, a former vice-chair of the Fed, speaking at last month’s Treasury market conference.

The BIS and other regulators are right to keep trying to make finance more resilient to shocks and less likely to require taxpayer bailouts like the still-controversial ones for banks in 2008. But sudden demands for liquidity will always arise and they will become more concentrated on the Treasury market. Unless we want to put all the risks and losses back into the hands of ordinary investors, the Fed will have to be ever-ready to turn Treasuries into cash.

More from other writers at Bloomberg:

-

Cracks Emerge in Treasury Bond Market: Liz McCormick and Edward Bolingbroke

-

The Last Charge of the Stimulus Brigade: Marcus Ashworth

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Paul J. Davies is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering banking and finance. He previously worked for the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.