(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The announced closure of the International Monetary Fund’s office in Athens feels like a landmark, even though Greece, unlike many other crisis-hit nations in recent decades, was emphatically not bailed out by the IMF. It’s a moment to reflect on whether Greece really has been bailed out by anyone.

Technically, Greece is no longer a country in crisis. It’s more indebted relative to its economic output than any other European Union member state: Its debt-to-GDP ratio stood at 180.2% at the end of the second quarter last year, compared with an EU total of 80.5%, and there is no significant downward trend. But the European Commission sees the debt burden as sustainable and projects that it will drop to 100% of GDP by 2041. A 2018 deal, which smoothed out Greece’s repayments, helped greatly with that.

Other indicators look bad but not catastrophic. Unemployment is down to 16.4% from a 2014 peak of 27.8%. The economic growth rate is finally in positive territory, projected by economists tracked by Bloomberg to reach 1.7% for 2019 and 2% this year.

From the IMF’s point of view especially, there’s little left to do in Greece. Last year, the country made an early repayment of 2.7 billion euros ($3 billion) on its relatively expensive debt to the IMF. Now, it only owes the fund, which made its last disbursement to Greece as long ago as 2014, a mere $6.3 billion out of a total of $340 billion in external debt.

But in effect, the crisis and the rescue efforts have cast Greece, an EU member since 1981, down to the economic level of some of the newest member states. Its per-capita GDP, adjusted for purchasing power parity, has stabilized at a little more than two-thirds of the average EU level, about the same as in Latvia or Romania. The high taxes forced on Greece by creditors have created an informal economy about as big, relative to GDP, as in these and other Eastern European countries.

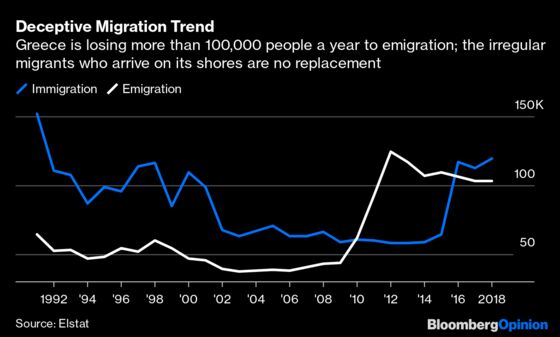

According to Elstat, Greece’s national statistical agency, net migration has been positive in the last few years, but that’s more of a problem than a happy development. Greeks have been leaving the country of about 11 million at a rate of more than 100,000 a year since the crisis started. The outflow only has been offset by the arrival of migrants from the Middle East and Africa during the recent refugee wave — a burden Greece struggles to process.

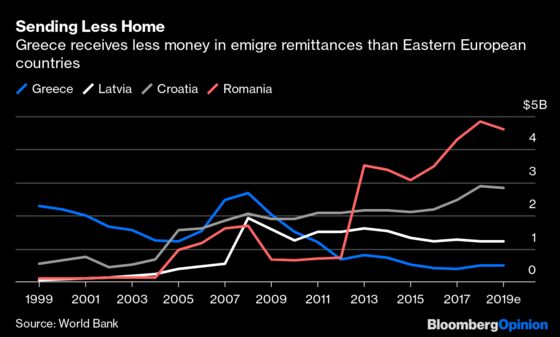

Unlike Eastern European countries, however, Greece has never received much of a remittance inflow from its emigres. In fact, such transfers of funds have even dropped since the crisis-driven mass emigration started.

Greece also has less flexibility to foster economic expansion than the Eastern European nations: Agreements with creditors forced it to run primary budget surpluses, and even despite low interest rates, its financing needs are much higher than the Eastern Europeans’ because of the sheer size of its debt pile. Romania, for example, has a government debt-to-GDP ratio of just 34%.

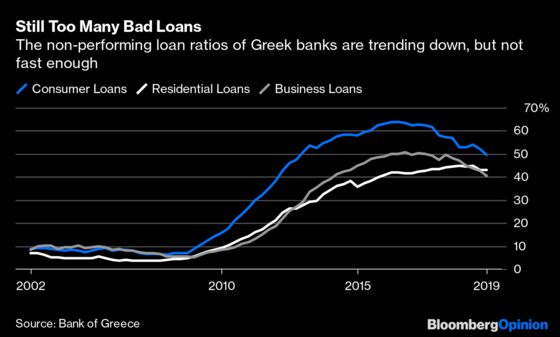

What’s more, unlike their Eastern European counterparts, Greek banks are saddled with enormous amounts of non-performing loans, which aren’t declining fast enough to allow banks to expand credit. The Greek banking system’s bad-loan ratio stood at 42.1% in September, the latest month for which data are available. In Romania, that ratio is below 5%.

Greece, in other words, isn’t just starting from a low base like the Eastern Europeans — it’s doing so while dragging around a ball and chain. The center-right government of Kyriakos Mitsotakis is trying to offload the bad debt from banks’ books and lower taxes, but Greek governments’ flexibility in fixing the economy will be limited long beyond Mitsotakis’s tenure.

In a way, the restrictions are fitting payback for what went wrong in Greece. In a September 2019 speech, Poul Thomsen, director of the IMF’s European Department, said Greece’s crisis was different from the contemporaneous ones in Spain, Ireland and Portugal. In those countries, adoption of the euro drove a private credit expansion that led to an “unsustainable demand boom.” In Greece, by contrast, it was the government that feasted, raising pensions and social transfers by 7% of GDP between the single currency’s adoption and the onset of the crisis. That, in Thomsen’s view, explains Greece’s bad fortune in facing a greater fiscal tightening than Europe’s other crisis victims.

By extension, Greece’s political elite must learn to live with the long-term restrictions. An obsessive spender needs to be separated from his credit cards. Contrary to what’s often assumed, Greece’s private creditors were punished, too, for supporting the government’s appetites — they took a major haircut in 2012.

In other words, a lot has been done to minimize moral hazard on the part of Greek politicians and private investors. But it still exists for the IMF and the EU, which have collectively worked out the punishment that came as part of Greece’s financial rescue. They won’t be responsible for any of the mistakes they made during the bailouts — underestimating the depth of the crisis, demanding the draconian tax increases, insisting on budgetary tightness even as it translated into continuing economic decline.

The IMF is getting paid back ahead of time. Yields on the bonds issued by the European Stability Mechanism to support Greece, are negative, so Europe can well afford to be lenient on Greece’s repayment terms. The Greek crisis has delivered tough lessons to Greece’s elite and to bankers. But the IMF and the European Union are free to handle the next crisis in the same bungling ways, battering the victim but taking on little of the cost.

Of course, the world doesn’t have to be fair, but Greece’s institutional creditors should consider shouldering more of Greece’s burden. If the Mitsotakis government, and perhaps its successor, make substantial progress in getting Greece’s economy to grow again and Greek emigres to come home, nominal debt cuts shouldn’t be ruled out. It’s not wrong to make Greece wear its ball and chain, but making it do so indefinitely is excessive.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Melissa Pozsgay at mpozsgay@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.