The Great Resignation Is Great for Low-Paid Workers

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- An estimated 3% of American workers quit their jobs in September, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported last week. That’s the highest percentage since the BLS started keeping track two decades ago.

This elevated quit rate has been given a name, the Great Resignation, and those who advise businesses have been offering bucketloads of advice on what to do about it. If my inbox is any indication, most of this advice is focused on how to retain knowledge workers or professionals or white-collar workers or whatever it is you want to call them/us. “Unresponsive managers and a failure to develop relationships with remote workers are primarily behind the exodus,” declares one consulting firm. Another’s survey reveals that 52% of knowledge workers “are likely to quit their job if company values do not align with their own.” More than half of technology workers say they suffer from job burnout, “and those who suffer from burnout are twice more likely to quit their job than those who don’t,” finds yet another survey. And so on and on.

But the sharp rise in quits over the past year has not been driven by knowledge workers upset about burnout or unresponsive managers or values mismatch. Consulting firm Mercer reports, based on employee surveys it has conducted, that “front-line and low-wage workers are leaving at rates higher than historical norms” while higher-paid office workers aren’t. My fellow Bloomberg Opinion columnist Allison Schrager’s analysis of Current Population Survey data found that college-educated workers haven’t been quitting or dropping out of the workforce at higher rates than before the pandemic, but less-educated workers have.

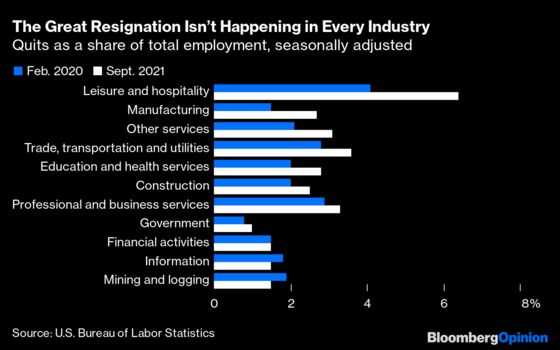

The BLS quits data isn’t broken down by pay or education but is sorted by industry, and industries heavy on knowledge workers aren’t seeing big increases in quit rates. The quits rate in professional and business services was just 0.4 percentage points higher in September than before the pandemic in February 2020. In financial activities it was unchanged. In the information sector, made up of telecommunications, publishing, broadcasting, motion pictures, software and most internet companies, the quits rate was down 0.3 percentage points. (It was also down in mining and logging, which is mostly the oil and gas business, but that’s another story.)

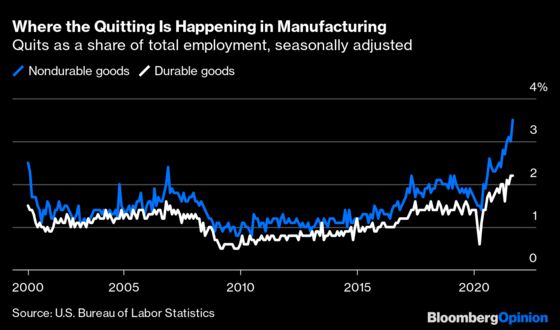

The biggest increases in quit rates were in sectors such as leisure and hospitality where office workers are few, working remotely seldom an option and wages low. Within manufacturing, the quits-rate increase has been much bigger in lower-paying nondurable goods (of which food manufacturing is the biggest part) than in higher-paying durable goods.

Earlier in the pandemic many of these low-paid frontline workers may have quit because of Covid-19 fears, child-care issues or other struggles with work-life balance. But in recent months most appear to have been quitting because they’re finding better jobs somewhere else — sometimes in the same sector, sometimes not. In nondurable goods manufacturing there were 222,000 hires in September versus 166,000 quits, while in transportation, warehousing and utilities (think Amazon.com Inc. distribution centers) it was 301,000 hires to 171,000 quits. Economy-wide, there were 6.5 million hires to 4.4 million quits.

Nick Bunker of Indeed Hiring Lab, who made me aware of the tilt away from white-collar industries in the quits data, sums it up like this: “The ‘Great Resignation’ is more a story about strong demand for workers, rather than a rethink of work among higher-income workers.” In other words, it’s not really about resignation at all, at least not as I think the term is generally understood. It’s about low-paid workers switching to higher-paying jobs.

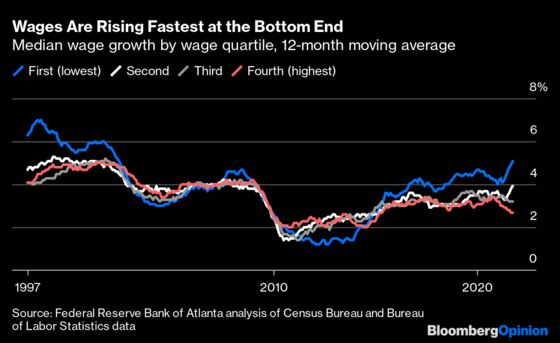

Such opportunities were few during a terrible stretch after the Great Recession. Pay started rising fastest at the bottom of the wage distribution in 2015, and the differential has grown since — although it’s still not back to where it was in the late 1990s.

Quitting is sometimes the only way to realize these pay gains. The Washington Post’s Greg Jaffe had a lovely story earlier this month about a walkout at the McDonald’s in Bradford, Pennsylvania, where the franchisee refused to raise wages. Asked the walkout ringleader: “Why would you want to work for a company that doesn’t value you?” He was able to entertain such deep thoughts because he already had a better-paying position lined up at a lumber mill in town and could be confident that his colleagues would land on their feet as well. That they did, with Jaffe reporting that the “McRejects” found new jobs for higher pay at McDonald’s In competitors Burger King, Dunkin’ Donuts and Tim Hortons, as well as the Save-A-Lot grocery and Crosby’s convenience store.

That doesn’t really seem like a Great Resignation. It is, however, pretty great.

Technically, 3% of nonfarm payroll jobs in the U.S. were quit in September. It's possible that some workers quit more than one job, and it's certain that I'm not counting workers who are self-employed or otherwise not reflected in the payroll jobs data.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.