Should Computer Science Be Required in High Schools?

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- This is one of a series of interviews by Bloomberg Opinion columnists on how to solve the world’s most pressing policy challenges. It has been edited for length and clarity.

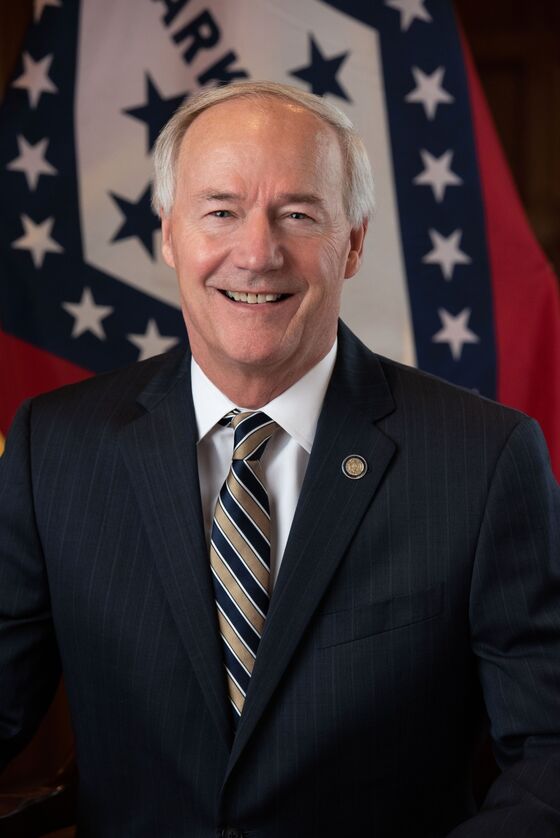

Romesh Ratnesar: You’re in your second term as governor of Arkansas and recently became chairman of the National Governors Association. In that role, you’ve announced an initiative to expand computer-science education in public schools across the U.S., building on Arkansas’ leadership in this area. Every public high school in Arkansas now offers courses in computer science, compared to just 47% nationally. What sparked your commitment to making computer science education a priority for your state?

Asa Hutchinson, governor of Arkansas and chairman, National Governors Association: There are two parts to it. As undersecretary of Homeland Security after 9/11, I had responsibility for overseeing the agencies that were designed to prevent a terrorist attack on our soil. You had to do that through technology — data analytics and software that took massive amounts of information to determine what posed a risk, what was safe for commerce and what needed to be targeted for inspection, whether a container or individuals or passengers on a plane. That experience with the importance of technology for security brought me to run for governor.

My granddaughter is the other part of the story. She was 11 years old when I ran for governor. With her dad, she built an app so that people could volunteer for my campaign and donate to it. I thought, if my 11-year-old granddaughter could do this, then this is something that’s really important for all of Arkansas — and you can learn it at a very young age.

RR: When you first introduced this idea of requiring every public and charter high school in Arkansas to offer classes in computer science, what sort of resistance did you encounter?

AH: Well first, there was a lot of rolling of eyes: you’re going to run for governor talking about computer coding? Once we passed the law requiring it in every high school, we had to overcome some resistance from educators, superintendents and the educational establishment. And then you had to sell it to students, particularly in rural areas, where maybe their dad works in the factory or the farm and they just could not visualize a future in which they were involved with technology. That’s why I went to over 80 high schools marketing computer science to the students. Once the demand started increasing and the students understood it, teachers embraced it very quickly, because they wanted to be able to satisfy their students’ needs and provide the courses that they wanted.

RR: How did you find enough teachers qualified to teach computer science? Did you retrain the existing work force or did you have to go outside and recruit new teachers?

AH: All of the above. When we started, we had fewer than 20 certified teachers across the state of Arkansas in computer science. Now we have close to 600. We provided the professional development and gave teachers confidence that even if they didn’t have a background in technology, they could learn it and could guide students and prepare them, because so much of this is self-learned. And we incentivized them. Our legislature gave $5 million every two years for the computer science initiative. We used a portion of that to provide $10,000 over five years to teachers who became certified in computer science and taught in the classroom. So that was $2,000 a year as an extra bonus for teaching it. All of that helped us to recruit and retain critical teachers.

RR: In a state like Arkansas, there’s a wide range of schools with different levels of infrastructure. How do you ensure that students in schools that have very few computers and might not have reliable broadband are getting the same quality of instruction as the kids in the more affluent parts of Arkansas?

AH: Equity is a challenge in every sphere of education. The gap might be even wider in computer science, but in some ways it’s also easier to close with concentrated effort. The first thing we did was to provide to every school access to high-speed broadband. But there’s still a gap because when the students go to their homes in a rural area, they don’t have the same network capability. This was magnified as a problem during Covid when we depended, in some instances, on virtual education. We’re investing hundreds of millions of dollars right now to expand broadband into homes in rural communities. It’s also harder to recruit teachers in the rural areas, and so we’ve had to devote special funds for our rural areas to make sure they have what they need to recruit and retain the teachers.

What Covid taught everybody was that you literally can run the world from your hometown in rural Arkansas if you have access to high-speed broadband and you know coding. Because people have been working remotely, they can visualize themselves working for a company in Houston or San Jose or Charlotte, or globally, while still living in a rural area. The pandemic showed the scale of the challenge but gave us some tools to overcome it as well.

RR: As a result of these investments, you’ve seen a tenfold increase in the number of students in your state who are taking computer science during high school. What impact has that had on the state’s economy? Are those students finding new job opportunities in Arkansas? Are more tech jobs coming to Arkansas because businesses know there’s a pool of people who have these skills?

AH: First, even though we’re a rural state in many ways and agriculture remains very important to us, but we do have the global campus of Wal-Mart, we have Tyson Foods, we have trucking companies that are engaged in logistics — and all of these older, established companies are now technology companies. It helps us to keep them here versus their moving their businesses out of the state. Second, my goal has been to create Arkansas as a micro hub of technology companies. We’re having some success there. We’ve had technology companies that started here and others that have moved in from the west coast to Arkansas, because we have a talent pool and a pathway for them to know that they can have the work force if they need it. So it has really exceeded my expectations in terms of the economic benefits.

RR: Public schools are asked to do a lot of things these days — some are just struggling to keep the lights on, keep students enrolled, make sure kids have basic proficiency in core subjects. As you try to build this out nationally and hold up Arkansas as a model, I imagine you are still going to face some questions from some educators who say computer science is really a luxury they can’t afford when they’ve got more pressing needs to deal with. How would you respond to that?

AH: They have to understand that this is a national security issue. Computer science really breaks down to cybersecurity, which we all know is a national-security issue. It’s also about the future in terms of blockchain, in terms of data analytics. Every industry globally needs more software engineers. Where are they going to get those resources? For America, we’re either going to produce the talent right here, or we’re not going to keep up with the technology, or we’re going to have to import all of our talent. The only option that’s acceptable to me and from a national-security standpoint is that we create that talent right here.

Students are going to continue to showcase the demand. I think educators will prioritize it when they understand the necessity of it for students. Computer science isn’t just an extra course, it is a core course. That’s why we now require it in Arkansas as a high-school graduation credit. The challenge nationally is to make sure everybody understands it can really fit in well with other subjects.

We don’t want to diminish arts education, or history, math and the other sciences. All of these are incredibly important for us. But in every field you go into — whether it’s agriculture and utilizing GPS in your farming operations, or using software in medicine, or electronic music or game design — you are going to be a more attractive talent in the work force when you have that background in computer science. In every sphere it has to be a basic and it should be required for graduation.

RR: What role should technology companies, in particular, play in helping to develop the curriculum?

AH: It’s in the best interests of businesses to have a talent pool coming in their direction. Getting businesses connected to schools is a greater challenge. That’s one aspect we want to do better in. Apprenticeships are important. And whenever somebody from industry comes in and talks to a class about technology, all of a sudden the students see it in reality, versus hearing the theory from the teacher.

One of the important parts of our computer science initiative in Arkansas is that we put money behind it. When you put money behind something, that shows the seriousness of the effort. It also allows us to fund competitions among the students so that they can showcase their skills and get cash awards, and teachers can be incentivized and rewarded. Industry can help advocate in those areas. And they can help to advocate nationally as we try to move this to a national platform. We don’t want a federal government mandate coming down. That doesn’t work. Education is always the role of the states, but industry can really help shape it.

RR: We seem to focus a lot on various divisive political debates playing out in schools and not enough on the more fundamental question of how to give students have the skills they need to compete going forward. What will it take to make computer science and STEM education in general a bigger national priority?

AH: It’s a challenge for our nation. We have local candidates and state candidates all running on national issues. They’re not talking about the bread and butter issues of education and crime and what we need to do to make our streets safe. We need to get back to the basics of education and economic development. That’s the role of leaders such as myself.

We do have a lot of divides. But computer science and technology education actually brings people together. One of the greatest areas of growth in our computer science program has been among girls taking coding. [Enrollment among] minorities has increased. Software will help develop the future [but] if we don’t have a diverse population involved in creating that future through technology, then we’re going to have gaps. It’s not going to be a complete future and it’s not going to be the America we want.

Romesh Ratnesar writes editorials on education, economic opportunity and work for Bloomberg Opinion. He was deputy editor of Bloomberg Businessweek and an editor and foreign correspondent for Time. He has served in the State Department, and is author of “Tear Down This Wall.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.