The Forgotten History of America’s Black Beach Resorts

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The first time I visited Bethune Beach, a short, narrow stretch of prime Florida coastline wedged between the Atlantic Ocean and the Indian River east of Orlando, I stood near the historical marker honoring the beach’s founding by Mary McLeod Bethune and took a long look around. It was a warm day in late December — beach weather — and people were enjoying the white-sand shoreline, fewer than 50 yards away, as the ocean glistened in the sun. Yet something seemed amiss. I rotated slowly to take in the view from every direction, to be sure I hadn’t overlooked anything.

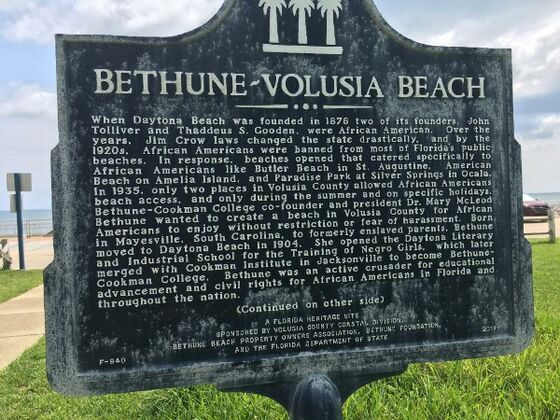

Bethune had started a school for Black girls in nearby Daytona in 1904. Armed with an unyielding will and an investment of $1.50, she built what is known today as Bethune-Cookman University.

Bethune was every bit as relentless in her efforts to create a local beach for Black people, who in Jim Crow Florida were excluded from public beaches except on the rarest occasions. If Black people could actually own a beach, she reasoned, they could enjoy a respite from the ritual humiliations and persistent threat of violence that shadowed their days. Bethune convinced a wealthy Florida developer in 1943 to sell her a two-and-a-half-mile strand in Volusia County, south of Daytona; it totaled 189.4 acres, with a mortgage of $132,000. Then she cajoled and browbeat a stable of wealthy Black men into becoming the first investors in the Bethune-Volusia Beach Corporation, founded in December 1945.

“For a long time the progressive citizens of America have recognized the strategic value of a beach resort on the Atlantic Coast owned and controlled by Negroes,” Bethune wrote. “Those of us who sincerely believe that recreation is essential to the good life should be encouraged to know that in the deep South great strides are being made.”

Despite Bethune’s efforts, development of Bethune Beach was slow and troubled. The postwar real-estate boom, like so many aspects of American life, was shaped by race. The G.I. bill subsidized housing, education and even business creation for qualified veterans. The most important qualification, however, seemed to be a veteran’s skin color. By 1950, the Federal Housing Administration and the Veterans Administration together insured half of all new home mortgages in the U.S. Each used race as a criterion not only for individual mortgages but also in the financing of entire subdivisions.

With the federal government undermining home ownership for Black citizens even as it subsidized it for millions of White citizens, the Bethune-Volusia Corporation began marketing lots on Bethune Beach not just in Florida and the Southeast but across the country. The pitch was two-fold: buying a lot was a good personal investment, and good for collective Black advancement, too.

Most of the tiny lots were sold on installment contracts. Buyers lacked the funds to purchase lots outright, let alone to attempt construction. For years, there was only one house completed in all of Bethune Beach. Yet Black visitors came nonetheless, piling in cars and buses to spend a day at the beach, then returning home by carefully plotted routes marked by Black restaurants and motels. On major holidays, hundreds, occasionally thousands, descended for cookouts, beauty contests, races and fun. As a few more homeowners built on their lots, they grew accustomed to taking in holiday guests. A granddaughter of original Bethune homesteaders told a researcher that her parents sometimes housed as many as 40 people overnight.

By the early 1950s, Mary McLeod Bethune, then in her late 70s, was pushing forward with the planned construction of a cinder-block motel, the Welricha, which was slated to feature 28 rooms along with a restaurant and lounge. (A 16-room beachfront motel was eventually completed.) But the nascent resort’s finances remained shaky. Distant investors who struggled to keep up $5 payments on a Black Shangri-La they’d never seen cut their losses when hard times arrived. Despite Bethune exploiting her connections to Black newspapers and other useful mediators, new investors were hard to come by. Black capital was scarce. Lots remained unsold.

In the summer of 1952 Bethune issued a public “S.O.S. Call — To the Negro Citizens of America,” published in various newspapers, pleading for financial investment in Bethune Beach. “We have struggled valiantly to hold to this property, because of the difficulty that Negroes have in purchasing Beach sites,” she wrote. “We need cooperation and reinforcement from Negroes who have faith in the working and investing strength of our own people. We want Negroes to own and control this Beach subdivision.”

It’s that vision of empowerment, buttressed by faith, which the historical marker at Bethune Beach is meant to honor. It was placed there in a small park overlooking the beach that Bethune had fought so hard to secure. It was no small matter fashioning a Black resort out of such unforgiving terrain. Yet Bethune’s investment advice could not have been more prescient. Lots that she sold for hundreds of dollars are now worth hundreds of thousands. Today, wealth abounds in Bethune Beach, where million-dollar homes prevail.

But as I stood by the marker, taking in the views, I was fixated on what I couldn’t see: Black people. I had driven the length of the town before arriving at this point. I hadn’t seen one yet.

***

In the annals of American racial pathologies, water holds a special place. Bodies of water were feared to be conductive of racial depravity or, worse, equality. One of the worst race riots of 1919 began in Chicago when a raft used by Black youths drifted into waters associated with a White beach. A local Florida ordinance from 1924 made it “unlawful for any white person or persons to bathe together with any negro person or persons ... in the waters of the Atlantic Ocean.” White America drained public swimming pools across the country in the 1950s and ’60s rather than integrate them, as Heather McGhee notes in her book “The Sum of Us.”

A classic photograph of late-era civil rights resistance was taken in St. Augustine, Florida, just up Interstate 95 from Bethune Beach, on the day before the Senate filibuster against the Civil Rights Act was finally broken in 1964. It shows a motel manager pouring acid in a swimming pool to drive off interracial swimmers who were protesting the Whites-only pool policy.

Water is also associated with wealth. Homes with swimming pools, beach access or even views of water are typically more valuable than homes without. And those valuable homes are mostly owned by White people.

The history of racial discrimination in housing has been getting increased attention, commensurate with greater recognition that the White-Black wealth gap is in significant degree a product of a socially engineered White-Black gap in housing equity. The dispossession of Black farmers and other landowners who shunned racist courts and exploitative lawyers only to find themselves untitled to their own land is likewise a story that’s become more familiar to many Americans. The racial battles waged on American beaches and in resort communities are bound to become better known as well.

University of Virginia professor Andrew Kahrl has spent years uncovering the national history of economic restriction and dispossession. Along with a cohort of Black journalists — Jamelle Bouie, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Nikole Hannah-Jones, Adam Serwer — who focus on the legal, structural and historical gears powering the inequality machine, Kahrl has been instrumental in documenting the efforts of White communities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to prevent Black people from profiting financially or even emotionally from national resources.

Kahrl’s research on racially disparate impacts of property assessments “paved the way for the attention it is getting now,” says Richard Rothstein, author “The Color of Law,” a landmark history of government-mandated housing discrimination. Kahrl’s research on beach property is especially vivid history. His 2012 book, “The Land Was Ours: How Black Beaches Became White Wealth in the Coastal South,” is a page-turner, and horror story, about coastal property values and race.

The drive of early Black entrepreneurs to create safe spaces for Black recreation and respite, in the face of overwhelming opposition, is a testament to how powerful the need was. Obstacles abounded. Black people had limited ability to raise capital — banks wouldn’t lend to them. Black patrons were harassed by local police. Black property owners had their taxes raised by hostile local governments. Rules, regulations and laws were suddenly changed to disadvantage Black enterprises. And when all else failed, uninsurable Black resorts burned not-so-mysteriously in the dead of night.

“As urban waterfronts and nearby seashores connected by rail grew in popularity and profitability in the first decades of the twentieth century,” Kahrl writes, “African American corporate investments in pleasure resorts increasingly fell victim to arson and other forms of racial terrorism by those who saw in such visible symbols of Black economic initiative an affront to relations of power being inscribed onto these new land and waterscapes.”

Over and over, Black entrepreneurs sought to develop scenic property where Black people could briefly escape the bedevilment that pursued them elsewhere. The imperatives of mental health were reinforced by those of physical health. For most of American history, safety was a strictly White prerogative. Black swimmers were routinely relegated to polluted streams, toxic shores and dangerous currents while cleaner, safer recreation was reserved for White people.

The quest for relief resulted in Black enclaves, however short-lived, up and down the East Coast, across the Gulf of Mexico and on to California. Florida, which had a longstanding Black population and has even more coastline than California, produced numerous Black beaches. Among these, American Beach was unique.

***

American Beach, located on Florida’s Amelia Island, about a two-and-a-half-hour drive north of Bethune Beach, was founded as “a place for recreation and relaxation without humiliation.” For a time, it seemed to beat the American system. The beach’s founder did as well.

Abraham Lincoln Lewis was a Black millionaire in Depression-era Florida. Lewis had been an uneducated but notably shrewd laborer when he joined a burial society — essentially a co-op that pays for members’ funerals — for Black people in Jacksonville in 1901. Lewis eventually took leadership of the organization and transformed the Afro-American Industrial & Benefit Association into the multi-faceted foundation of the city’s Black commercial life.

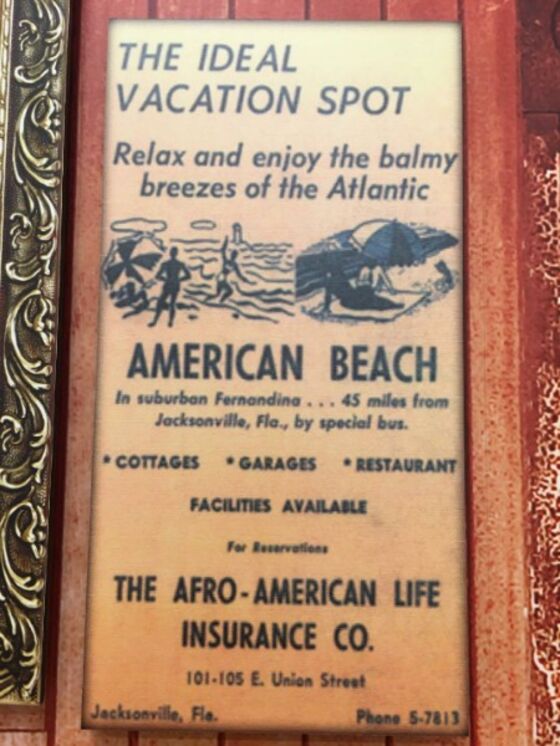

As the company’s capital grew, it changed its name to the Afro-American Life Insurance Company, investing in real estate and venturing beyond insurance to provide mortgages and other forms of financing routinely denied to Black people. (As one White insurance analyst noted, in justifying the exclusion of Blacks from industry policies, they had an unfortunate tendency toward “premature death” compared with “higher races.”)

Lewis moved into a stately home in Jacksonville and rode in a chauffeur-driven Lincoln. By 1941, the company boasted that “the highest salaried men and women of our race in our state are found on the semi-monthly payroll of the Afro-American Life Insurance Company, a company who for forty years has never missed a payday or for any cause delayed salary payment.”

Lewis had a knack for manufacturing what Mary McLeod Bethune could never fully grasp: Black capital. In 1935, in the maw of the Great Depression, the insurance company’s pension department bought 33 acres on Amelia Island with 1,000 feet of beach fronting the Atlantic Ocean. Two other parcels were acquired later — the final one in the form of a grant from the U.S. government under President Harry Truman.

After the initial purchase, trees were cleared, a compact grid of streets was built and homes were constructed, including one for Lewis. The beach became a destination for Black people from Jacksonville and surrounding areas, and Black merchants arrived to cater to them. When the company sponsored annual picnics on the beach for employees and their families, Lewis obtained a highway escort by Florida state troopers to protect the travelers from harassment by local authorities.

“For us,” writes Marsha Dean Phelts in “An American Beach for African Americans,” her memoir and history of the beach, “going to American Beach was the equivalent of going to Disney World today, in terms of its popularity and prestige. It was a place where dreams came true just by being there, the place for family gatherings or community get-togethers, the place to see and gape at the prominent personalities of the community.”

In Jacksonville, as in other American cities, supply and demand in the housing market restricted Black mobility both geographically and economically. With fewer housing options, Black residents were charged higher rents to live in lower-quality housing. With more expenses, lower incomes and restricted access to better jobs, saving money was, for many, little more than a fantasy.

One consequence of strictly enforced segregation was that affluent and poor Black residents shared the same neighborhoods. On Amelia Island, they proceeded to share the same beach. “The social integration of Black downtown Jacksonville was exactly what Black Jacksonville preserved when it built an escape from the city,” writes Russ Rymer in “American Beach: A Saga of Race, Wealth and Memory.”

With few Black vacationers able to afford second homes, American Beach was democratic by necessity. “Across Gregg Street from the row of beachfront houses built by the company’s elders, the Pension Bureau built cottages for Afro employees. The A.L. Lewis Motel was owned by the company but open to anyone with eight bucks a night,” Rymer writes.

Ultimately, American Beach was a company town. Its existence depended on the wealth created, cultivated and preserved by the Afro-American Life Insurance Company. When Lewis died in 1947, the business, and town, were thriving. By the early 1960s, both were in decline.

On July 2, 1964, when President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act, opening new vistas to the nation’s Black citizens, American Beach was poised for disaster. It arrived weeks later, on Sept. 10, in the form of Hurricane Dora. The storm thrashed the beach, ravaged homes and destroyed businesses. The beach never recovered from the powerful combination of 1964: the arrival of Dora and the departure of legally enforced segregation.

After 1964, Phelts writes, “All along the shores of the East Coast, blacks explored areas that had once been off limits. The three-day weekends at American Beach shrank to one day; the Sunday visitors and day-trippers no longer stayed overnight. Loaded buses no longer caused a bottleneck at the crossroads. With so little business most of the restaurants and resort establishments closed.”

Once a paragon of perseverance and ingenuity, American Beach devolved into eccentricity. It remains a curiosity today. The town exists outside the familiar grid of race and class that defines American geography and shapes perceptions of market value. The view from American Beach’s rutted streets is not just unusual, it’s disorienting. Within the same few square blocks are million-dollar homes and rotting hulks still teetering decades after their demise. History hovers everywhere, partly due to the pervasive structural wreckage and partly due to an abundance of historical markers noting where So-and-So’s house once stood, or still does.

The crumbling remains of Evans’ Rendezvous, a once-boisterous 200-seat club featuring live music and dancing, sit abandoned on the beachfront. Next door is another long-vacant hulk with million-dollar views. Right across the narrow street, steps from the beach, is a forlorn, empty lot.

Carlton Jones, a Black Jacksonville developer and pastor with a second home on American Beach, estimates the racial composition of the beach’s roughly 165 households at about 60/40 Black/White. He notes that the tiny community has largely succeeded in fending off the giant developments that encircle it, including the Ritz-Carlton and the Omni Amelia Island Resort, where rooms with views similar to those from Evans’ Rendezvous go for more than $1,000 a night. But the Omni acquired a portion of American Beach years ago, placing maintenance facilities there. And everywhere surrounding American Beach, overwhelmingly White retirees indulge in branded experiences of golf and luxury.

American Beach seems to have defied the old real-estate maxim defining property value — “location, location, location.” Yet it’s hard to believe such defiance can last forever. Johnetta Cole, the former president of Spelman College and the great-granddaughter of Abraham Lincoln Lewis, is building a house there. (Her sister, MaVynee Betsch, was a celebrated opera singer in Europe who returned home and became a local eccentric, giving away her money and living for decades in — and more or less on — the beach.)

It’s not hard to imagine a future in which American Beach resembles Oak Bluffs on Martha’s Vineyard, or Sag Harbor on Long Island, where multiracial elites mingle. But today, the beach appears stalled between glorious past and uncertain future. Or perhaps it’s trapped there.

***

At 89, Hester Bland is property rich. She and her family — she has three middle-age children — own two adjacent homes in Bethune Beach, both of which abut the Indian River. From her rear porch she has unobstructed views of the sun setting behind the marsh, and she can watch the trajectory of rockets that launch from nearby Cape Canaveral. The family’s two homes are among the last structures before the south end of Bethune Beach gives way to the pristine Cape Canaveral National Seashore.

Bland is a slight, bespectacled woman who speaks softly and surely. She’s also one of the only Black property owners left in Bethune Beach. In late July I sat with her at her dining room table, accompanied by her daughter Jacqui Colyer, to try to understand why.

Bland’s journey to Bethune Beach was painstaking. As a young nurse married to a Port of Miami longshoreman, Bland, who came from a farming family, did not like renting. With tutoring assistance from a Jewish women’s group on Miami Beach, Bland took courses on weekends to become a registered nurse and earn more.

“When summertime came,” she recalled, “and the kids got out of school, I went to school, picked them up and took them directly to the train station. I had their bags already packed, their lunches packed. I put them on the train and sent them to grandma for three months. So for three months I was able to work two jobs. I’d work at the hospital, give them eight-and-a-half hours. Then I’d leave and go to a nursing home and work for another eight-and-a half hours, until 11.”

Bland and her husband saved enough for a down payment on a home. But real estate was treacherous for Black buyers, who rarely had access to conventional mortgages. The developer who sold them their home gave them a five-year interest-only mortgage. It was a common ruse. After five years the mortgage would balloon, the payments would become unaffordable and the developer would reclaim the house and begin the lucrative con all over again with another buyer.

The Blands’ lawyer — members of Miami’s Jewish community played a supporting role in the family’s success — warned them about the financial trap. To escape it, each month Bland went to the post office and bought a $35 money order. (The Blands had no bank account.) “Mom had a shoe box that she put all the little money orders in,” said Colyer. “At the end of the five years, the shoe box was literally full of money.”

When Bland showed up to pay off the mortgage, the developer initially refused to accept her money. But the Blands and their lawyer, Irwin Block, insisted that he must. With the equity they acquired, the Blands later purchased a bigger house in Miami, though not their preferred home in Miami Shores, where a covenant prohibited a sale to Black buyers.

Eventually, when the children were grown and departed, the Blands purchased a lot, and then another, in Bethune Beach. In 1977, they built their own home and ran water lines from their friends’ house to their own until they managed to get service from the county.

Good fortune, grueling work schedules, disciplined saving and stubborn perseverance landed the family in a prime location at Bethune Beach. But by the time they arrived, most other Black property owners were gone, having cashed out for a small profit or simply abandoned the dream of a Black-owned beach in favor of something less exotic and closer to home. Even the neighbors whom they had followed from Miami — one of the original Bethune families — are now gone. Today, fewer than a handful of Black homeowners remain.

Sonny Ellison got a bargain as a result. During Bethune Beach’s transition from Black to White, there was a period when land was available but many White people were hesitant to buy. Others bought, but waited for a racial sifting before building. Ellison, a 74-year-old White Christian Southerner who voted for Bernie Sanders, demonstrated for Black Lives Matter and chose Willie Mays over Mickey Mantle in boyhood playground debates, profited nicely on the racial arbitrage.

“When I built my house in ’76, the roads were still all dirt and there was no mail delivery and no garbage pickup,” Ellison said in a telephone interview. “It was a rural beach area, you know, not frequented that often except mostly on holidays by the Black people.”

Ellison says he grew up around Ku Klux Klan members and surfed at Bethune Beach in the early ’60s, when he and his White friends from a neighboring town referred to it by replacing “Bethune” with the n-word. By the time he moved in, however, White investors were already staking claims.

“It started in the sixties,” said Joe Stevens, a Black Bethune Beach resident whose beachfront property has been in his family for decades. “However, in the early seventies, a number of folks from over in the Orlando area — it was as if they all of a sudden discovered Bethune Beach as a wonderful real estate opportunity.”

White investors from Orlando weren’t the only ones to take note. “At the same time,” Stevens said, “the county is recognizing more and more that this Bethune Beach property is valuable beachfront and riverfront property, just like Daytona Beach and every other place in the county. So they start taxing it that way. And now these folks who bought this property with all the best of intentions are discovering that they really can't afford to hold onto the property, that it’s beginning to cost them as opposed to helping them.”

Ellison purchased his two lots, on the Indian River side of the main road, from two different White owners. Since then, property values have soared in Bethune Beach, as they have up and down the coast. The land started out in the hands of Black people. But the large investment gains have gone almost exclusively to White people. To hang onto the land, and realize its full potential, would have required capital. Too few Black investors had it.

Ellison has reaped a windfall. “It’s one of the few things in my life that I actually made a good decision on, even though I went against other people’s advice,” said Ellison, a former president of the Bethune property owners association.

***

In 2015, long after the racial transition was completed and Black faces had become rare, Ellison proposed a memorial to the beach’s founder, Mary McLeod Bethune. Stevens, who had a family connection to Bethune, was excited by the proposal and offered to help.

But not everyone living at Bethune Beach wanted to make a big deal about the founder. A large display might attract unwanted attention, they said. “There was the fear that by erecting a memorial, you would be drawing more Black people to the area,” said Stevens. “And they didn't want more Black people coming to the beach.”

In the end, Bethune Beach erected a few discreet historical markers. In size and style, the lone marker on the beach side of the road is nearly identical to the marker in front of Evans’ Rendezvous in American Beach, which commemorates a “Florida Heritage Site,” and honors its ruins.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Francis Wilkinson writes about U.S. politics and domestic policy for Bloomberg Opinion. He was previously executive editor of the Week, a writer for Rolling Stone, a communications consultant and a political media strategist.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.