(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Wise old market heads often remark that the bond market rarely lies and it often leads the stock market. This is particularly apposite at the moment, with too much cash kicking about and forcing bond, house and equity prices ever higher — infinite money chasing finite assets. It is putting the Federal Reserve in something of a dilemma: It has to try and avoid the policy mistake of withdrawing stimulus just as the rising economy might be on the verge of hitting an air pocket.

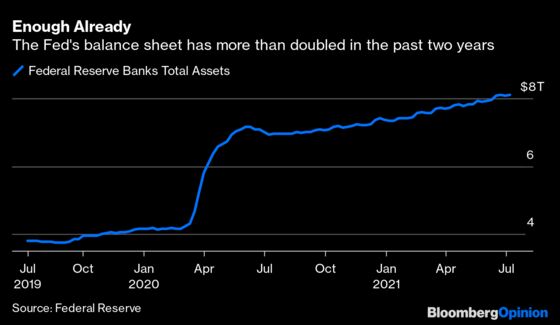

The late August central bank symposium at Jackson Hole was looking like the perfect venue for Fed Chair Jay Powell to signal another attempt at trying to taper quantitative easing. In fact, the Fed might have missed its window to ease off its monthly $120 billion QE bond buying spree.

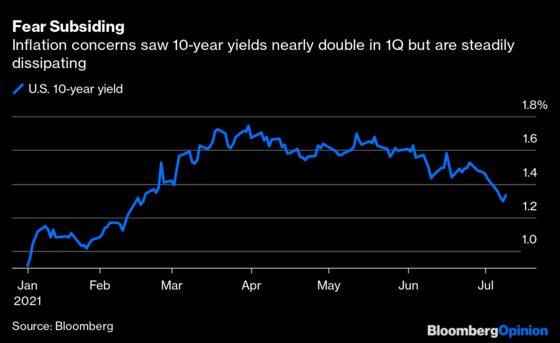

There is a real need to stop sucking out all the available float from the U.S. Treasury and mortgage bond markets. The Fed’s balance sheet is now over $8 trillion. On a net basis it is buying all supply this year, leaving banks, pension funds and foreign investors scrabbling around not to miss out on what has become quite the squeeze. Why the Fed is still buying $40 billion per month of mortgage-backed bonds when U.S. house price gains are at their highest for over 30 years is head-scratching stuff. Since the start of the second quarter, 10-year Treasury yields have fallen 40 basis points as the inflation fear trade that drove yields higher in 1Q unwinds.

The baffling bond price surge comes a time when it is too early to tell whether the uptick in inflation is transitory. It is creating an impression that the sugar rush of all that fiscal stimulus may soon wear off. On Thursday, Deutsche Bank AG’s macro-strategist Jim Reid released an investor survey he conducted to try to figure out what’s behind the most sustained fall in bond yields in nearly two years. The factors that respondents placed most weight on were supply/demand technicals followed by concerns over secular stagnation. In other words, they foresaw low inflation but also lower growth.

It’s not as simple as shutting off stimulus now. We may not be able to handle the truth of having to be weaned off QE forever, especially if the economy or stock market falters. A repeat of the 2013 taper tantrum is a risk the Federal Open Market Committee will have to weigh up very carefully, but not from a fear of sharply rising bond yields so much as the other moving parts of the economy. One of the best lodestars for economic momentum, the ISM manufacturing purchasing managers survey, peaked at 64.7 in March, with the June reading at 60.6. It is the direction of travel that is key for forward-looking equity markets, not just the overall level of growth.

Unfortunately, the shine is starting to come off the global pandemic reflation trade, and it’s not helped by the worrying global spread of the delta variant. This was highlighted by San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly in an FT interview on Thursday. She urged caution on reining back stimulus. The equity market is realizing the mood music might be changing, even though the major U.S. indexes are still hovering near all-time highs. European stocks on Thursday put in their worst performance this year and Japanese stocks are barely positive. Chinese stocks have turned negative. This would not be a good time for the Fed to taper if the U.S. stock market fell off its precarious perch.

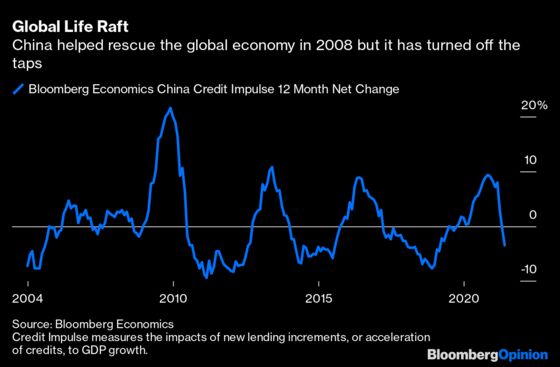

The Fed needs to look to China. As growth falters, the Asian behemoth has just made a volte face on its own version of tapering. China’s credit impulse (new credit as a percentage of gross domestic product) has plunged this year. On Friday, this prompted the central bank to cut by 0.5% the reserve ratio requirement that commercial banks need to hold with it, thereby pushing more money back into the banking sector. China realizes it has overdone clamping down on credit growth.

It’s far from a precise science but if this leads to a weaker yuan (which would be a key stimulus for the export-led Chinese economy) the knock-on effect on a stronger dollar could have ramifications for much of the rest of the world — particularly developing countries that benefit from a weaker greenback. Dollar strength has gone hand-in-hand since late May with the fall in Treasury yields. That has yet to impact U.S. equity valuations but luck may not hold out.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Marcus Ashworth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European markets. He spent three decades in the banking industry, most recently as chief markets strategist at Haitong Securities in London.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.