The Container Shipping Industry Is Raking It In — for Now

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The financial transformation of the container-shipping industry has been astonishing: Almost overnight, operating box ships has become a license to print cash.

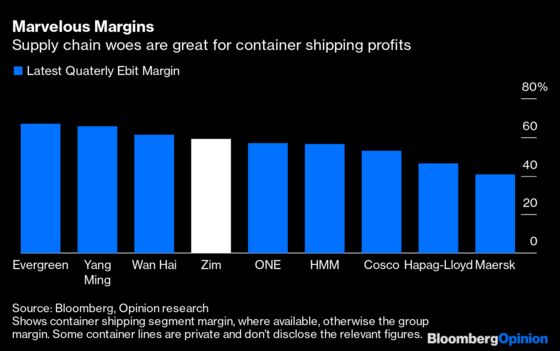

Following an initial public offering last year, one of the top container lines is now listed in the United States: Zim Integrated Integrated Shipping Services Ltd. Like peers, the Israeli carrier is swimming in money, much to the delight of key investor Deutsche Bank AG. Zim had an operating profit margin of 59% in the quarter ended Sept. 30, which is double the same measure at Apple Inc. and not far off vaccine producer Moderna Inc.

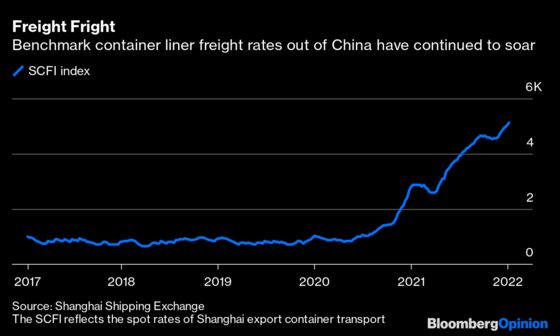

To recap briefly, port congestion wrought by the pandemic has been terrible for most of us, but it’s meant the container lines can charge pretty much whatever they want for cargo space.

The industry will report about $190 billion of operating profit for 2021, according to maritime research firm Drewry, which is more than the operating earnings at Apple and Microsoft Corp. combined. It looks increasingly like 2022 will deliver a similar bounty.

These windfall profits haven’t gone unnoticed by investors — shares of Taiwan’s Yang Ming Marine Transport have gained 1600% in dollar terms since the start of 2020, for example, while shares of Denmark’s AP Moller-Maersk A/S are near a record. There are hopes a more consolidated and digitized industry is at last becoming more disciplined and efficient; with the cash they’re generating container lines are able to pay down debt, fund carbon-cutting investments and make value-creating acquisitions in areas like logistics. And of course they’re increasing shareholder payouts.

But there’s still a lot of skepticism — and no wonder: For much of the past decade, container lines struggled to make money: Competition was brutal and carriers kept splurging on new ships. Between 2008 and 2019, the average operating profit margin was negative 1.5% for the industry, notes JPMorgan Chase & Co. analyst Samuel Bland. Much of this underperformance was self-sabotage.

Hence, like a lottery winner who’ll never enjoy another a big payday, the liners aren’t now fully trusted to make the most of their good fortune. And though the resolution of supply-chain blockages keeps getting delayed, many investors assume the current conditions won’t last beyond this year. What, then, will a “new normal” look like?

Zim is a good example of the debate. The world’s 10th-largest container line by capacity underwent a debt restructuring in 2014, appointed new management and last year joined the New York Stock Exchange – a rare American debut as the large container lines are either private or listed in Europe and Asia.

Talk about a phoenix from the flames. The shares have quadrupled since the IPO. This performance was bested only by the SPAC that’s merging with Donald Trump’s nascent social media venture, according to Bloomberg data on U.S. listings in 2021.

It was well set up to seize advantage of the extraordinary market conditions: Trans-Pacific services, which cater to booming U.S. consumer demand and are currently among the most lucrative, account for around 40% of its container volumes. It also has unusually high exposure to very elevated short-term (spot-market) freight rates, rather than lower value multiyear contracts.

Yet despite upgrading profit forecasts several times last year and increasing payouts to shareholders, Zim’s $7.5 billion market capitalization is less than twice the roughly $4.3 billion of net income it’s expected to report in 2021.

Amid a big rotation from loss-making speculative technology shares into less sexy, but more cash-generative “value stocks,” some investors wonder if that comparatively modest valuation still makes sense. With freight rates still rising and the omicron variant threatening to further prolong port disruption, it might not.

Zim has caught the attention of retail investors and several large hedge funds – Renaissance Technologies, Citadel Advisors and Marshall Wace were big holders as of last September. However, at least one prominent backer isn’t sticking around.

Having acquired a debt and an equity position following Zim’s financial restructuring, Deutsche Bank is in the process of exiting its winning bet – it held a 12% stake when last disclosed in the summer. In total, the bank could net almost $1 billion from the wager, Bloomberg News reported in June when Zim’s share price was lower than it is now.

Expectations of selling by the German bank and other post-restructuring holders may have slowed Zim’s stock market advance but there are probably other factors holding it back too.

Not withstanding a recent purchase of second-hand container ships, the vast majority of Zim’s fleet is leased and hence it’s exposed to soaring charter rates: it’s not just container lines that can charge more; so can shipowners. Zim’s average charter length has increased to two years, creating potential for a profit squeeze if freight rates were to plunge suddenly.

Lease-adjusted net debt will also rise from the current negligible levels when Zim takes delivery of 25 chartered lower-emission vessels starting in 2023. And it’s not the only liner beefing up their fleet: At the end of 2021, new container ship orders had ballooned to almost one quarter of the existing fleet, according to Alphaliner data.

Given the industry’s rotten track record, it’s hard to be confident the sailing will be this serene. The larger the share of the industry’s cash haul that gets hands back to shareholders, the less the temptation there will be to squander it on risky expansion. Perhaps then investors will accept container shipping has really changed its spots.

More From This Writer and Others at Bloomberg Opinion:

- Supply-Chain Crisis? What Supply-Chain Crisis?: Karl W. Smith

- Companies Made Heaps of Money. And Workers?: Chris Bryant

- Greenflation Is Real and It's Not Transitory: Javier Blas

Based on estimated 2021 earnings

In the first three quarters of 2021 Deutsche booked 400 milion euros ($450 million) of Zim-related revenue

Zim's new vessels will start arrivingwhen previous leases expire, giving it more capacity flexibility.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies. He previously worked for the Financial Times.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.