(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The Labour Party’s Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell recently promised 55 billion pounds ($70.64 billion) of extra spending a year on investment, if elected on Dec. 12, considerably more than the 20 billion in extra annual spending on capital projects that Chancellor of the Exchequer Sajid Javid has pledged. Voters might wonder, if a little more spending is good, why wouldn’t a lot more be even better?

The Tories have come up with a neat way to answer that. After Mark Sedwill, the head of the civil service, blocked a government plan to publish a report on Labour’s fiscal plans (deemed a breach of impartiality rules), Conservative Party number-crunchers put out their own, which found that Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party plan will add up to more than 1.2 trillion pounds of new spending. That’s a whopping number, even spread over a five-year parliament. It’s also probably fictional. The methodology suggests the Conservatives began with a trillion in mind and worked backward until there were enough inputs to reach it.

The Tories hardly needed to exaggerate. Even if Labour’s splurge doesn’t quite reach the trillion-pound mark, McDonnell’s spending plans are still orders of magnitude bigger than those of the Conservatives. They would raise capital spending to levels not seen since the 1970s. The major difference in the Labour plan, though, is less the quantum of spending than the kind of spending envisioned, the new fiscal rules that would govern it and the radical philosophy that underpins the program.

To cross the trillion-pound threshold, the Conservative Party accountants added up all the commitments in Labour’s 2017 manifesto (611 billion pounds, by their measure) and then tallied the various new commitments that were voted on at the Labour Party conference in Brighton this year. This includes nearly 70 separate policies, from nationalizing the Big Six energy suppliers (which the report puts at 124 billion pounds) to abolishing private schools (35 billion pounds) to a car scrappage scheme (800 million) and free TV licenses for people over 75 (2.47 billion).

It’s not known, however, in which form any of these will appear in the actual 2019 party manifesto. Abolishing private schools and confiscating their land and endowments, for example, is a policy the party leadership is clearly uncomfortable with. The Conservatives could have waited a week for Labour’s actual plans and figures to be published (manifestos setting out a party’s legislative intentions are generally released about three weeks before the election). But where’s the fun in that? And by then the Conservatives will need to defend their own manifesto pledges and costs. You can see why they wanted to play the trillion-pound card early.

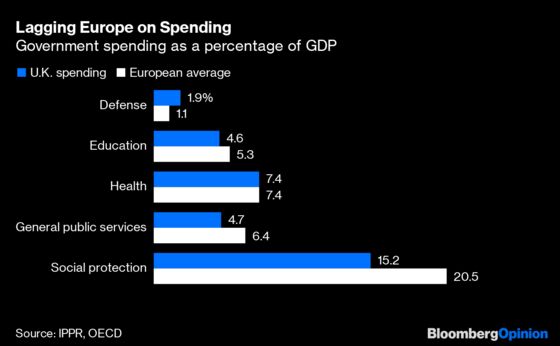

Boris Johnson’s Tories would be better off making the case for more public sector investment, done responsibly. Years of austerity and squeezed public budgets have left chronic underinvestment in many parts of Britain, from social care — long-term non-medical care for the elderly and the disabled — to the education sector and infrastructure. Substantial investment is also needed in commitments to reduce carbon-dioxide emissions. Overall, average public sector spending as a percentage of GDP is about 40% in the U.K., compared with almost 49% among similar European countries, according to the Institute for Public Policy Research; and Britain underspends Europe in these key sectors, as the chart below shows.

But while clearly Britain could do more, a state sector that grows too large and bloated would soon require more taxation and borrowing and could crowd out private sector investment. Tory plans would expand the government’s room for capital expenditure but still require a balanced budget within three years.

The trillion-pound tally was designed to paint a maximally unflattering portrait of Labour. Yet the headline number isn’t the biggest problem with Labour’s approach to fiscal policy. The party’s 2017 manifesto pledged to lower the national debt, giving voters some comfort that a Labour government wouldn’t write checks it couldn’t cover. But now, rather than promise simply to reduce the national debt as a percentage of GDP, McDonnell speaks about the “overall balance sheet” and a broader “public sector net worth” measure.

The big difference in this new scheme is that the value of any asset purchased with borrowed money would be used to balance out the debt, so that “net worth” wouldn’t change. This gives Labour more room to spend. Nationalizing utilities wouldn’t break the bank because the value of the utilities themselves would offset the borrowing needed to purchase them. All of this would depend, however, on the markets being willing to lend the government great amounts of money at low interest rates. That might not be a problem initially, but what about over time, when growth slows, or if the government proves a poor manager and the value of the assets declines? The Labour vision also depends on raising a great deal more from taxation.

These fiscal rules are rooted in governing philosophy. McDonnell speaks of “an irreversible shift in the balance of power and wealth in favor of working people.” Labour puts government at the center of economic life, a paradigmatic shift for Britain. Most people would support policies that genuinely lift the living standards of the poorest, reduce inequality, raise productivity and promote economic growth. To do that, however, Labour would have to be very careful not to discourage investment and innovation. France’s bloated public sector is a living monument to how vast government bureaucracies can depress job creation. And it goes without saying that all this becomes even more challenging under any Brexit scenario.

That said, the trillion-pound figure could also backfire on Conservatives. On the hustings, Labour candidates might find it advantageous to sidle up to voters and say “Hey, all those extra zeros on the spending figures there are a feature, not a bug.” The Tories would do better to focus on quality over quantity. Voters are smart enough to grasp the difference.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Mary Duenwald at mduenwald@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Therese Raphael writes editorials on European politics and economics for Bloomberg Opinion. She was editorial page editor of the Wall Street Journal Europe.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.