The Bond Market Is Dismissing a U.S. Default. Should You?

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It can be hard — and often outright painful — to follow the debt-ceiling drama in Washington. Republicans want Democrats to pass an increase to the debt limit on their own but are filibustering to prevent a simple-majority vote? House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer won’t raise it through a reconciliation bill? Can anything get done before Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s Oct. 18 deadline?

Fortunately, there’s a simple way to gauge how panicked bond traders are about an unthinkable U.S. default. It involves looking at the rates on Treasury bills that mature around when the government will run out of resources to meet the nation’s commitments. If there’s cause for concern, then the T-bill curve will “kink” around the drop-dead date, with investors demanding a greater premium to own obligations that could be in jeopardy if lawmakers can’t get their act together.

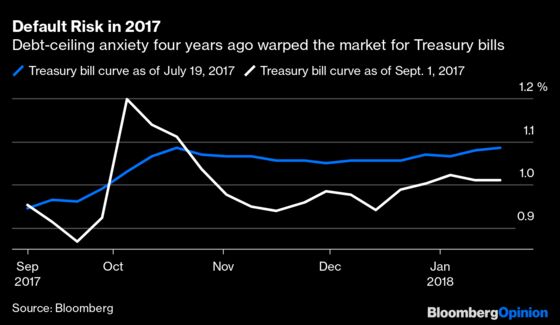

Here was an extreme case from September 2017, just days before a debt-ceiling deal was reached, in which certain T-bills offered rates that were more than 30 basis points higher (in hindsight, practically free money):

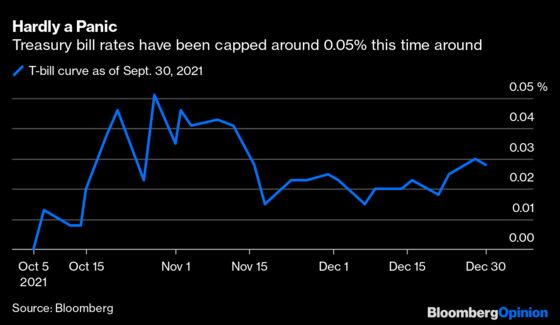

Fast-forward to the present, and the T-bill curve looks considerably more tame. It requires zooming in near the zero lower bound. The rate on debt maturing Oct. 19 briefly breached 0.05% after Yellen specified the date she expects the U.S. to hit the debt ceiling, and bills due Oct. 21 almost reached that level when she hinted there are a “few days” of room after the deadline:

Jim Vogel at FHN Financial referred to the spike as the T-bill market’s “max distress point in this cycle.” If that’s all the panic that bond traders can muster, is that a sign that a U.S. default is out of the question?

I’m hardly a political expert and don’t care to handicap the brinksmanship of Democratic and Republican leaders in the House and Senate. But it does seem as if there’s reason to suspect the T-bill market is underpricing the risk that the U.S. runs through the debt-ceiling deadline.

The Federal Reserve’s reverse repo facility is likely playing a part in the tranquility thus far. I wrote in May about how the central bank was absorbing a record amount of cash — almost half a trillion dollars at the time. Use has only surged further since then, reaching an unprecedented $1.6 trillion on Thursday. This is by design: As part of its policy decision last week, the Federal Open Market Committee increased how much each counterparty could place with the facility to $160 billion from $80 billion.

It’s also noteworthy that the reverse repo facility offers a 0.05% rate on cash parked at the central bank. That has functioned as a way to prevent the shortest-dated T-bill rates from going negative, but it might also serve to keep the maturities at risk from the debt-limit standoff from veering too high.

“Repo markets remain calm and there have been little money fund outflows thus far unlike in 2011 and 2013 when there were significant outflows ahead of the debt ceiling X-date,” TD Securities rates strategists Priya Misra and Gennadiy Goldberg wrote in a report Wednesday. “Outflows may be avoided this time given the availability and heavy usage of the Fed’s RRP facility (as an alternative to bills).”

The unprecedented actions taken by the Fed during the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic are a reminder that it has sweeping powers to avoid disaster. TD Securities noted that in previous go-arounds, the central bank discussed actions it could take to support market functioning. For instance, it could simply buy any T-bills that were at risk of default or swap them with other Treasury bonds. When compared with purchasing high-yield exchange-traded funds, such maneuvers look like normal parts of the Fed’s toolkit.

Other bond-market observers see a growing likelihood of the same pattern emerging as during previous showdowns. “Bills with mid- to late-October maturities will become increasingly difficult to trade,” Thomas Simons and Aneta Markowska of Jefferies LLC wrote in a report on Tuesday. “Yields on these bills will continue to rise relative to surrounding maturities. They will then rally instantly when the debt ceiling is raised. This type of market reaction has become the established playbook.”

They also cautioned that “at this point, we have no opinion on exactly how the debt ceiling will be raised.” And yet, like just about everyone, the analysts expect that “somehow, some way, the debt ceiling will be raised before Treasury runs out of cash and/or misses an interest payment.” Even Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell said the debt limit would be lifted, “because we always do.”

- Increase the debt limit as part of a broad reconciliation bill. (It’s unclear if that can be ready within weeks.)

- Increase the debt limit through a separate, stand-alone reconciliation bill. (It would be the second of the budget year, and the norm has been just one each year. It would also take up a lot of time.)

- Make it so debt-limit increases can’t be filibustered. (It’s unclear whether Democratic Senators Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona will support this.)

- Eliminate the filibuster altogether. (Manchin and Sinema almost certainly won’t agree to this.)

My Bloomberg Opinion colleague Karl Smith likes the reconciliation bill route and would use the opportunity to raise the debt limit so high that it’s effectively never a constraint again. Pelosi and Schumer have said they’ve ruled out reconciliation as an option, which another colleague, Jonathan Bernstein, suspects is setting up a scenario that leaves wavering Democrats with little choice but to put another dent in the filibuster (option No. 3 above) or else risk a default.

Either way, the setup for the coming weeks looks potentially more harrowing than the T-bill curve would seem to suggest. Maybe after 18 months of dealing with a global pandemic, bond traders are unperturbed by the typical antics in Washington. Maybe they have confidence that Yellen and Fed Chair Jerome Powell will be the adults in the room while Congress bickers. Regardless of why Treasury bills have remained so placid, watch the usual indicator for signs that investors are starting to brace for the worst.

Some unorthodox options include the grass-roots effort to "Mint the Coin," as championed by Bloomberg's Joe Weisenthal, andinvoking the 14th amendment to nullify the debt ceiling entirely.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.