The Big Question: Will the Taliban Rule Afghanistan Again?

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- This is one of a series of interviews by Bloomberg Opinion columnists on how to solve the world’s most pressing policy challenges. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Nisid Hajari: President Joe Biden has announced that U.S. troops will leave Afghanistan at the end of next month, ending NATO’s 20-year involvement in the country. The U.S. intelligence community has reportedly predicted that once the U.S. withdraws, the Afghan government may collapse within six months, with the Taliban potentially returning to power. You’ve covered and written about Afghanistan for decades. Your 2000 book, “Taliban: Militant Islam, Oil and Fundamentalism in Central Asia,” chronicled the rise of the Taliban and became a bestseller in the West after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks. You have a unique viewpoint on what the Taliban’s resurgence means for the country’s future. Are you surprised by how rapidly the Taliban have been making gains since Biden’s announcement?

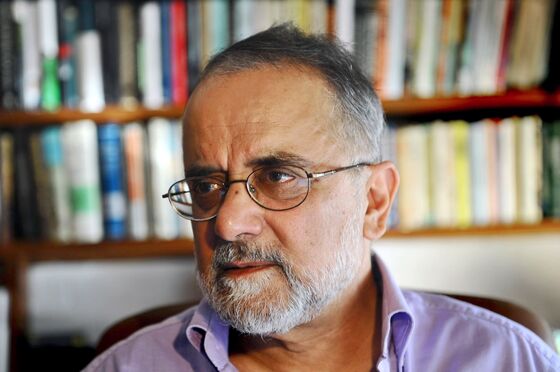

Ahmed Rashid, author, “Taliban: Militant Islam, Oil and Fundamentalism in Central Asia”: Yes, definitely. It’s been a big surprise to the Afghans, to the Americans and to outside observers. I think all parties in this conflict have made horrendous mistakes. I think the Americans gave away too much to the Taliban. Afghan President Ashraf Ghani has not been able to unite his politicians and warlords around him. There’s a very divisive situation in Kabul. The country’s neighbors have all claimed that they want to see peace, but have not been really helpful.

And the Taliban still, after a year and a half of negotiations, have not told the Afghan people what they want. They don’t believe in democracy, or do they? We have no idea. There is a younger generation of Taliban who may be more desirous of some kind of representative government. But there’s an old guard of commanders and people influenced by al-Qaeda. Some of them have been in Guantanamo. They are very hardline. And they don’t believe in what they consider to be Western political ideas.

NH: Are you surprised by how resilient the movement has been? After 20 years, they’ve been beaten down, mutated and are now reborn.

AR: The essence of the Taliban’s longevity is that they had a very secure sanctuary in Pakistan. That was the crux of America’s problem, that the Taliban were able to replenish themselves. Right now, for example, wounded Taliban are in hospitals in Pakistani cities. The Afghan government is not able to provide that kind of facility for its own troops, many of whom who are stuck in faraway areas of Afghanistan. The second problem has been, I think, the lack of a real American strategy [since 2009], when President Obama sent thousands of troops into Afghanistan — or even earlier than that after 9/11, when there was an opportunity for the Americans to negotiate with the Taliban. That is what many Taliban wanted, but the Americans rejected the idea.

NH: How different is this Taliban from the one that you wrote about in your first book?

AR: Well, the Taliban I met with initially in 1993, who then swept through Afghanistan, were very innocent, in a sense, very naive. They had very little concept of basically anything except fighting. They had no ideas on rebuilding Afghanistan or how to govern. It was not seen as a particularly practical movement, but they promised an end to the warlordism and the civil war. And that encouraged a lot of people to join them and accept them. After they captured Kabul in 1995-96, then they became one more warlord party, and started trying to invade northern Afghanistan and put down all the other ethnic groups. Their ability to preside over a new kind of government in Afghanistan was absolutely lost because they took several years to capture the rest of the country. And once they did that and started ruling the country, they had no idea how to do it.

As for how they’re different now, I think they’ve experienced a great deal. For example, they never allowed media in the ’90s. Now they are media-savvy, something they learned from al-Qaeda. But there are still enormous concerns about how they will govern. They don’t have an educated elite. A lot of the second- and third-generation Taliban have grown up in Pakistan in refugee camps and are better educated. But whether they’ll be allowed to come to the forefront in a Taliban regime is doubtful.

NH: The original movement was very tightly controlled from the top, very centralized and hierarchical. Is it still that way?

AR: It’s highly centralized. But the most extraordinary thing, I think, which has surprised many people, is that it’s very disciplined. There were divisions within the Taliban in the mid-’90s and after 9/11. But over the last year or two, the negotiations with the Americans have prompted a rallying around the flag for the Taliban. They have been far more disciplined and united, both in military terms and in political terms, than the government in Kabul. And, of course, their military forces are inspired by the fact that now they are close to conquering Afghanistan once again.

They’re also very keen to be recognized by the international community. They love traveling around the region, visiting Moscow and Central Asia and Iran. And they consider themselves now as the legitimate rulers of Afghanistan, who should be acknowledged by the international community. This is something that the Americans and international community can hold over the Taliban; it could be used as part of the negotiating strategy.

NH: All these neighboring countries are now reaching out to the Taliban, in part because they’re worried about the spillover of violence or drugs or refugees and so on. Are the neighbors playing a useful role here?

AR: I think the Americans lost a real opportunity earlier. If they had brought in the United Nations to put together an alliance of neighboring states and then exerted a common pressure on the Taliban, we might have seen a different outcome than what we’re seeing right now. Instead, what has happened is that, first of all, all the neighboring countries — China, Russia, Iran, the Central Asian republics and, of course, Pakistan — all started buttering up the Taliban, as it were, as they became more successful. During the peace negotiations, America gave in to many of the Taliban demands, without really taking into account the Afghan government. So what we’ve seen is a desperate failure of the international community to come together and use their presence as one trigger in order to put pressure on the Taliban. What we need is much greater unity in the international community.

NH: You don’t think it’s too late for that?

AR: I really am a firm believer that it’s never too late. The reality of the geopolitics in the region, however, is very much against any kind of major effort by the international community. Many of these countries, countries like Iran and Russia, carry out policies which are to their advantage, not to the advantage of bringing peace to Afghanistan.

China is going to become the major beneficiary of whatever happens in Afghanistan, because Afghanistan is full of minerals. The idea of mineral exploration and exploitation is certainly uppermost in China’s mind. And it’s quite logical because Afghanistan can’t export important minerals to anywhere else in the world except through the Chinese, who can build a land route through northern Afghanistan into China.

NH: Can the Chinese expect that a Taliban regime would create enough stability that they could profit from development and from mining?

AR: Well, the Taliban have gone out of their way to reassure the Chinese. I think the Taliban would be more than willing to facilitate Chinese exploration and exploitation of Afghanistan’s minerals.

NH: How much influence does Pakistan still have over this version of the Taliban compared to 20 years ago?

AR: It’s a different kind of influence. Twenty years ago, Pakistan was giving money, arms, weapons or ammunition or food — it was fully backing and supplying the Taliban in its offensives across Afghanistan. I don’t think that’s the case now, but there is enormous influence because, simply, the Taliban are situated in Pakistan. Their families, the leadership committees, their incomes are all focused on the leadership sitting in Pakistan. One of the very big mistakes made was the failure of international community to persuade Pakistan to send the Taliban back to Afghanistan, or at least threaten to do so, because the Taliban are very comfortable here. They’re not threatened in any way by any Pakistani pressure. And, of course, this has become a very big issue for the millions of Afghans in Afghanistan, who are asking, “Well, what the hell do you think you’re doing? Sorry, you claim to be Afghan, yet you’re launching wars against Afghanistan?” For many Afghans this is a sellout of Afghan nationalism — you’re using your foreign base in order to attack your own country and kill your own countrymen.

NH: If the Taliban do gain power in Kabul, what do you think their rule would be like? First of all, would they keep their promises to cut off ties to al-Qaeda?

AR: Well, I can’t see how they can do that. Al-Qaeda is both a military and a political force in Afghanistan. The leaders of al-Qaeda, many of them are married into Afghan society, especially the Pashtun population. And there’s a very close proximity between the Taliban in the field and some of the al-Qaeda people, who have been helping them develop new weapons, training, etc. The Taliban would have to be extremely ruthless and literally kill off al-Qaeda fighters. I don’t see them doing that. There’s a lot of wishful thinking here. Maybe some Taliban in the past would like to have seen al-Qaeda leave Afghanistan, but to do that in a peaceful manner is not going to be easy at all.

NH: And how do you think they will treat women and minorities again, compared to 20 years ago?

AR: They have promised that they will allow limited girls education. That means girls will be able to go to school up to perhaps fifth or sixth grade, but no more than that. It still has to be seen what policies they will use for human rights groups, civil society, women, teachers. Women form 40-45% of teachers in schools. Women are nurses and doctors. And if the Taliban come in and pull out all these women from the workforce, it will lead to even more catastrophic results for them. I think [Taliban leaders] will attempt to bring some of the younger cadres who are better educated into making policy, but they also have to watch the hardliners, the commanders who’ve been fighting and dying on the front lines. They will say, “We want the old Taliban government back.”

It’s a very tricky thing to manage and manipulate. How many concessions will they give on the social front, especially regarding women? How serious is the western threat to refuse to recognize the Taliban government if it comes into power and does not give women equal rights? There are a lot of unanswered questions at the moment.

NH: Of the various possible outcomes — the government holds on, or the Taliban take over or there’s a messy civil war — where do you see things most likely heading?

AR: It is very difficult to say, but I would predict that there will be continued fighting. The Taliban will try and take more and more territory [but] they won’t attack the major cities. They’ll expect some kind of surrender, or something like that. I think the international community will become less and less relevant. [We’ll see] the Afghan government resisting but losing ground. I certainly wouldn’t give a dire prediction, as some American commanders have done, by saying the government will collapse in three months or six months. Remember that the CIA predicted that after the Soviets withdrew, the Afghan communist government would collapse in six months; actually, they lasted three years in power. So, I would be very careful about making such predictions.

NH: You’ve been covering the story for decades now. What’s your personal feeling about what’s transpired in Afghanistan, the tragedy of it?

AR: I’ve been incredibly depressed, to tell you the truth. I was there covering the Soviet invasion and the withdrawal, the breakdown of the government, followed by the civil war. And so yeah, this is a repeat of a repeat of a repeat. And in the middle of this, of course, are the Afghan people, the majority of whom do not want the Taliban back and do not want any kind of extreme political system which will restrict their basic freedoms of education and jobs and things like that. It has been very depressing to see Afghanistan fall back like this — and the international community making so many mistakes once again.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nisid Hajari writes editorials on Asia for Bloomberg Opinion. He was an editor at Newsweek magazine, as well as an editor and writer at Time Asia in Hong Kong. He is the author of “Midnight’s Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India’s Partition.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.