The So-Called ‘Techlash’ Is Mostly in the Minds of the Media

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Remember how, in late 2018, the Financial Times declared “techlash” — the backlash against the giant U.S. technology companies and all they represent — word of the year? It also made Oxford Languages’ word-of-the-year shortlist then, but lost to “toxic.” To judge by the amount of negative publicity the companies continue to generate, techlash is still with us — but as far as both markets and users are concerned, it’s an empty word.

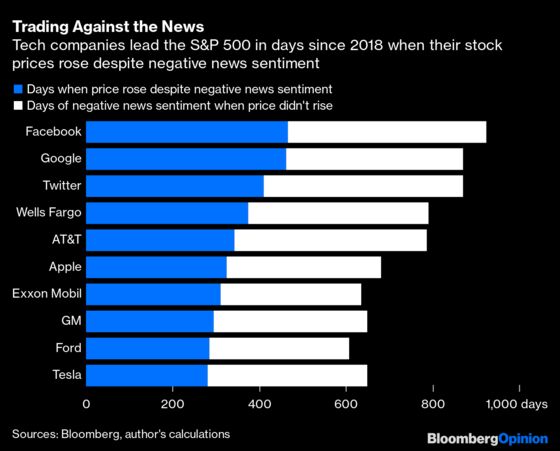

Every year since at least 2018, Facebook Inc. has led the S&P 500 companies in the number of days it faced negative news sentiment , and Alphabet Inc.’s Google and Twitter Inc. have been in the top 10. Facebook averaged 255 negative news days in 2018 through 2020 and has had 157 such days so far this year; Google and Twitter haven’t been far behind. But the ceaseless beating the companies have been taking in the news contrasts with the relentless rise in their stock prices. In 2018 and 2019, Facebook was the S&P 500 company with the most days when its stock price rose despite negative news sentiment. In 2020 and 2021, Google took over the top spot, with Facebook directly behind.

You could seemingly publish anything about these companies, their privacy-invading data-gathering practices, their promotion of pernicious political views and anti-vaccine propaganda, their monopoly power; you could even report on enormous fines imposed on the firms by regulators in Europe and the U.S., on lawsuits and antitrust proceedings — yet nothing would deter investors from buying. Since the start of 2018, Twitter’s market capitalization has increased by a factor of 2.8, Google’s by 2.6, and Facebook’s has doubled; the market cap of the S&P 500 has, meanwhile, increased a mere 69% — and these years have been when news sentiment has been consistently worse for the three tech firms than for any of their S&P 500 peers.

Arguably, the market has been reacting to the companies’ stellar financials — Google’s net income, for example, has grown by more than 30% a year during this time, and Facebook’s profit growth has averaged more than 40% — rather than to all the negative coverage. Ordinary users, meanwhile, have grown to regard the tech whales as evil. This year’s Edelman Trust Barometer showed the lowest-ever public confidence in technology companies, at 68% compared with 76% in 2017; in the U.S., trust in tech is even lower at 57%. Trust in social media as an information source is also at the lowest level ever.

You can’t easily reconcile these trust levels with the user numbers that the tech companies report to investors. Facebook says it has 1.9 billion daily active users, up 460 million since the first quarter of 2018; Twitter has 206 million, up 86 million. And even if the companies exaggerate these hard-to-check numbers by, for instance, not adequately counting users with multiple accounts, the steadily growing profits aren’t, after all, the result of price gouging — that’s not an accusation the Googles and Facebooks of this world have faced, yet. Instead, they reflect advertisers’ continued reliance on them, a reliance that would not be there if the ads didn’t convert to sales.

If users really considered the tech leaders evil, they’d abandon them in droves. Sure, network effects are hard to overcome, as my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Parmy Olson recently wrote, using the example of Facebook’s WhatsApp messenger, which appeared to bleed users after a change in privacy standards but ended up showing exemplary resilience. The power of these effects can be frightening: A U.S. government ban on Huawei’s use of Google software has all but killed the Chinese company’s then-market leading Android phone business, driving a high-quality hardware producer into a ditch because most users couldn’t imagine a Google-free life. And yet viable alternatives do exist, even in heavily monopolized areas such as internet search, not to mention mobile messaging; it’s just that the household names aren’t really any less attractive for most people than these alternatives. They aren’t evil enough for the daily user to go to any trouble at all.

When regulators take action against Big Tech, they understandably react to media reports — that barrage of negative news sentiment. The media, however, are Big Tech’s direct competitors in battles for audience attention and advertising dollars; I’d argue that we journalists are naturally motivated to consider Google, Facebook, even Twitter evil, no matter how objective we try to appear. I’ll be the first to admit that I’m biased in my thinking about them: These companies have all but ruined the professional world and the industry in which I started out and which I came to understand and love. Most officials and politicians grew up in my world, too; to them, reacting to sustained media sentiment like the kind that has developed around Big Tech is a matter of long practice.

Yet when it comes to ordinary users, the professional media are yet another increasingly unreliable source. We may gloat about the falling trust in the social media, but the same Edelman Trust Barometer shows the lowest confidence in traditional media since at least 2012 — 53% globally, down from 63% in 2018, at the beginning of “techlash”; 59% of respondents say that journalists intentionally mislead them and that they are more interested in pushing ideologies than in reporting facts. With majorities feeling that way, no wonder people don’t attach much importance to media attacks on tech.

To give a recent example, ProPublica, the nonprofit organization that promotes investigative journalism, has revealed the little-known fact that contract workers check not just the messages reported by users as pernicious but also those that came immediately before them; rather than deny this practice, Facebook has said it’s normal to examine the context when complaints are made, and that doing so doesn’t undermine the privacy protections accorded by end-to-end encryption. As a journalist, I’m inclined to side with ProPublica — but to an everyday user, even if she takes notice of the controversy at all, it pits one relatively untrustworthy source against another.

Given the news climate and regulators’ behavior, tech companies are, of course, among the biggest lobbying spenders. According to OpenSecrets, Facebook spent $19.7 million last year and $9.6 million so far this year on lobbying. But these amounts are tiny given the scale of its operations. If techlash were real, they would be woefully insufficient to defend the social networking giant from popular anger. As it is, the media will keep chipping away at tech power, and regulators will bite, sometimes painfully. But they will not undo the highly questionable business models that sustain digital advertising leaders; users just don’t care enough for a tech counterrevolution to break out.

I’m in constant search of alternatives to the tech giants’ services. I’ve replaced them everywhere I could, and I’ll replace the services I’m still using as soon as comparable alternatives become available. Yet I have no illusions about people like me undermining Big Tech’s market power in any meaningful way. There are enough of us to keep its smaller competitors alive, but that’s the extent of it. Techlash, let’s face it, is a niche phenomenon.

Bloomberg uses supervised machine learning to determine the sentiment in news stories from the point of view of an investor who holds a long position in a stock. The indicator used here is the daily average news sentiment.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is a member of the Bloomberg News Automation team based in Berlin. He was previously Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He recently authored a Russian translation of George Orwell's "1984."

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.