Shein's $100 Billion Valuation Is a Win for Fast Fashion

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Asked about upstart Chinese fast fashion brand Shein at annual results three years ago, the management team of British retailer Boohoo Group Plc burst into laughter.

“We could say we’ve never heard of them, but we won’t,” Executive Chairman Mahmud Kamani joked.

“We hadn’t until a few years ago, in all honesty,” his co-founder Carol Kane added.

“We are aware of them, but it doesn’t worry us in the slightest,” Kamani concluded.

Anyone older than Generation Z likely would have had the same response until recently. But make no mistake. Like Boohoo — whose shares are down by more than 60% since that call, in the face of Shein’s eye-watering competition — we’re all likely to feel the impact of its $5 dresses and $10 jeans very soon.

The retail juggernaut is weighing a funding round at a valuation of $100 billion, and is in talks with investors including General Atlantic about raising roughly $1 billion, people familiar with the matter told Bloomberg News this week.

Those numbers aren’t particularly outlandish. Shein may post $20 billion in revenue in 2022, according to Morgan Stanley, enough to overtake Fast Retailing Co. to make it the world’s fourth-biggest apparel retailer. Valuations of at least five times sales are more or less a rite of passage for fast fashion brands in their pomp (Boohoo was valued at as much as 10 times its sales at one point) and would seem more than merited by Shein’s double-digit growth rate.

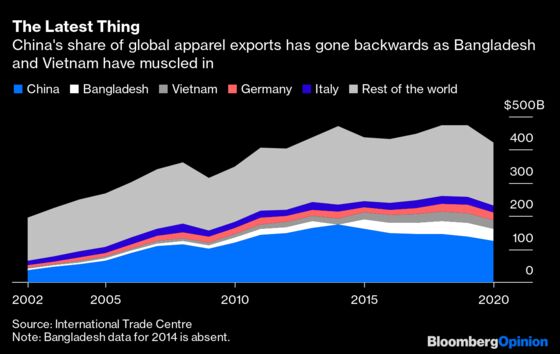

It’s a sign that China’s apparel trade, long thought to have been losing ground to rivals in Bangladesh, Vietnam and even Europe, still has ample life left. It’s evidence, too, that fast fashion, far from slowing down, is only accelerating. The cutting edge is moving from the speed with which clothes can be produced, to predicting consumer tastes before consumers even know them.

In some ways, Shein’s business is thoroughly conventional. Rather than counting on a global network of factories or high-tech automation, the core of its supply chain wouldn’t look out of place in the 19th century. Based on a report last year in Jiemian, a local business news website, the company runs as a tight-knit group of more than 300 suppliers sweating under ceiling fans and turning out hundreds of pieces a day on tabletop sewing machines.

Inditex SA’s Zara managed to revolutionize fashion in the 2000s by narrowing the lead time to get new clothes from concept designs to retail stores from months to weeks. Shein takes things a step further, with the product cycle taking just a few days at best. That’s mostly a result of old-fashioned efficiencies, too, such as putting in small orders and using local garment shops. Most are within a five-hour drive of its headquarters in Guangzhou, Bloomberg reported last year. The majority are in a single suburb.

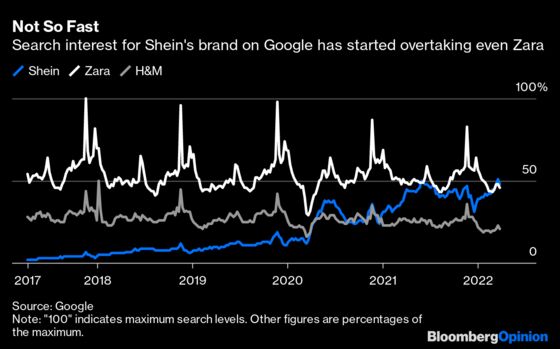

What’s unique about Shein isn’t its supply chain, but how it’s married that traditional style of business to a blistering pace of market research and customer acquisition. Founder Chris Xu has a background in search engine optimization — the dark arts of getting your results to the top of Google’s rankings — and those talents are evident in Shein’s vast social media presence. It’s the most-visited fashion website globally, and Google searches for the brand recently overtook those for both Hennes & Mauritz AB’s H&M and Inditex SA’s Zara:

In its meteoric rise, Shein has attracted its fair share of criticism, accused of everything from selling racist phone cases, ripping off designers, and contributing to overconsumption. It’s also benefited from some quirks of Trump-era tax policies in both China and its end markets that have allowed the company to undercut the competition.

Still, the biggest threat to Shein at this point isn’t a backlash from any of those angles. Inditex and H&M were once the poster children for unethical, disposable fashion. But as their core demographic has aged they’ve cleaned up their image and moved upmarket — something Shein is already doing with its MOTF brand. While those tax benefits certainly give the business an unfair advantage, that edge may prove surprisingly resilient, too, given China’s desire to support future-facing export industries and Western governments’ reluctance to slap costs on one of the few product categories where prices are going down these days.

The larger risk to Shein, in fact, is the same one it’s now posing to conventional fashion brands: that the barriers to entry for world-bestriding apparel retailers keep getting lower. Once upon a time, Zara and H&M laid waste to the conventional rag trade. Then Asos Plc and Zalando SE put those store-based retailers on the defensive with faster, cheaper, online-only models. Shein’s overnight arrival as the new giant-killer suggests that pattern is far from played out. In a business that’s always moved in seasons, winter will one day come for Shein, too.

Related at Bloomberg Opinion:

-

Anxious Shoppers Hurt Asos and the Online Boom: Andrea Felsted

-

What Did Your Favorite Brand Do in the War, Daddy?: Ben Schott

-

From Gucci to De Rucci, Innovation Always Grew From Imitation: David Fickling

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.