Russia Tried ‘Energy Dominance,’ and Markets Bit Back

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Russia and Ukraine, locked in a decades-long bad marriage when it comes to natural gas, just agreed to extend the misery a little longer. The arrangement by which Moscow had the gas and Kyiv had the pipes worked fine when both flew the hammer and sickle; not so much since their nominal divorce, with Ukraine moving out and Russia ultimately trying to move back in.

Geopolitical intrigue persuades even the most disinterested to take notice of energy markets. Yet, as a new history of the intertwined Russian and European gas industries shows, destiny is often shaped by the prosaic. There is plenty of drama in “The Bridge” by Thane Gustafson, an IHS Markit expert on Russian energy, from secret Cold War-era meetings in an Austrian castle to the tale of Ukraine’s former prime minister, revolutionary and one-time “gas princess,” Yulia Tymoshenko.

The bigger story concerns a lower-key kind of revolution, chiefly in technology and economics. And it is one reshaping not just gas in Russia and Europe, but energy markets worldwide.

The beginnings of the Russia-Europe gas “bridge” in the 1960s were complicated by the Iron Curtain, of course, but were, in commercial terms, pure vanilla. Russia needed money and technology (especially steel pipe and compressors) to develop its vast Siberian gas reserves, and the one market that could supply those things and also needed the gas was Western Europe. Early deals with Austria and, especially, the two Germanies had a barter-like quality. Which was just as well; in the absence of liquid energy markets, no one had a clue what the real “price” of gas was.

Gas is different from oil because it’s much harder to transport or store. By and large, you need a physical link, usually a pipeline. Building these costs a lot, and bankers are more amenable if you show them a signed long-term contract. Typically, these were structured to price the gas as a function of oil — a liquid market — meaning the seller was exposed to some risk if oil prices fell. On the other side, the buyer committed to take or at least pay for a minimum quantity of gas, meaning they were exposed if demand fell. Everyone’s happy, more or less.

Until they’re not. Besides the Berlin Wall, Ronald Reagan’s and Margaret Thatcher’s neoliberal tendencies took a pick-axe to the old gas bridge. By the early 1990s, just as Russia’s gas revenue was becoming “the mainstay of a failed state,” as Gustafson writes, ideas about shifting Europe’s energy markets away from vertical integration and opaque contracts toward choice and transparency began spreading eastward from the U.K., with Brussels just across the Channel. Gustafson chronicles the long battle undertaken by the European Commission — and especially competition heads Neelie Kroes and Margrethe Vestager — to break up the chummy club that was the Continental gas market and ultimately take on Gazprom PJSC’s long-term contracts.

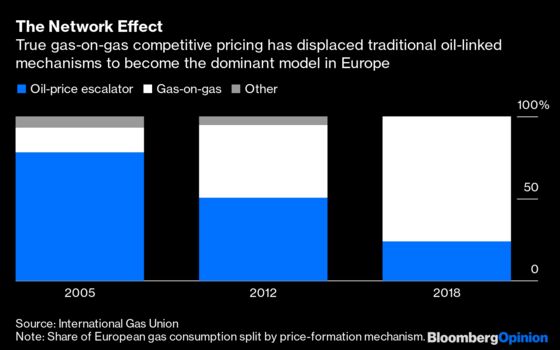

Ideology will only get you so far, though. What allowed the European Commission to assert its program was a mixture of time and technology. Since the 1960s, Europe’s isolated municipal gas networks had spread across the map like ivy, creating a continent-wide network. Networks — especially incorporating liquefied natural gas terminals — mean you aren’t beholden to one supplier and their steel umbilical cord. Add in the ability to trade gas in real time due to ever more powerful computing, and the building blocks are in place to create a liquid, competitive market with transparent pricing.

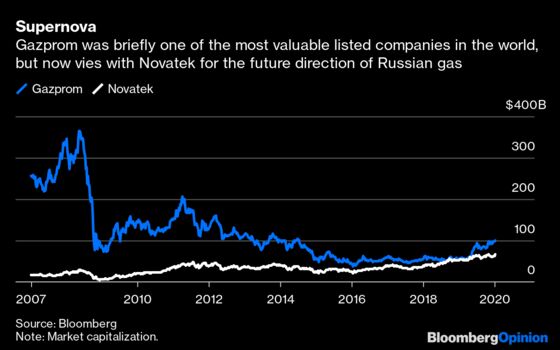

Gazprom was understandably resistant to this sort of thing, preferring the certainties, relationships and, of course, leverage of the old bridge. It’s tougher to browbeat an anonymous hedge fund in London than a functionary in some eastern European gas ministry (just ask Belarus). That said, Gazprom adapted well in certain respects, such as building an international trading operation. Yet institutional resistance to change also left it flat-footed, particularly when it comes to LNG. President Vladimir Putin, whom Gustafson describes as “an energy geek,” saw reasonably early that LNG was the future, and he ultimately bypassed Gazprom in lending tacit support to the rise of independent operator Novatek PJSC.

Geek Putin may be; mastermind would be a stretch. His strong-arm tactics via gas-supply cutoffs in 2006 and 2009 served mostly to push Ukraine further away, damage Gazprom’s reputation and, above all, demonstrate the energy weapon worked better back when customers were isolated, gas-hungry dependents rather than networked counterparts with options. Even Ukraine has loosened Russia’s grip, in part via dramatic declines in the country’s energy intensity.

Putin is a fast learner, though. His championing of LNG, along with that recent tactical Ukraine deal and new pipelines to Germany, Turkey and China, demonstrate an understanding that one way to deal with the diversification of Russia’s biggest gas customer, Europe, is to diversify its own options. Even here, though, it is worth pointing out that efforts to build alternative export routes, such as the Blue Stream pipeline to Turkey, began before Putin’s ascent to power.

For me, the most important line in “The Bridge” is where Gustafson notes that, despite Western Europe’s dwindling domestic gas production, its strengthened network provides greater security: “It matters less today who supplies the gas than that market forces create checks and balances.” This is a defining aspect of the transition away from the 20th century’s largely oligopolistic energy models. Rapid demand growth and the geographical inequities inherent to fossil-fuel resources favor suppliers. The rise of sophisticated networks, along with fuel-on-fuel competition and sheer conservation of energy, are changing that.

There is a lesson in “The Bridge” for Washington, which, having spent decades successfully countering energy potentates by fostering liquid markets and efficiency, now seeks to exert raw power via its “molecules of U.S. freedom.” This is an anachronism in an age of networks, albeit one that reflects America’s seeming disenchantment with those networks.

As for Russia, it’s adapting to the new commercial realities (and their impact on old geopolitical norms). Still, with hydrocarbons accounting for almost half the federal budget and the energy sector generating the lion’s share of export revenue, the country remains chronically under-diversified at an important level.

And the world continues to move on, most importantly with respect to climate change. In a recently published critique of Moscow’s energy strategy to 2035 — sub-titled, tellingly, “Struggling to Remain Relevant” — the authors observe that “the climate agenda is last and least in the order of priorities.” Yet it is this that presents an existential challenge to Russia’s energy income, regardless of this or that pipeline, with timing being the big variable. How Russia remakes itself for the energy transition is, thankfully, the subject of Gustafson’s next book project.

Tatiana Mitrova, director of the energy center at the Moscow School of Management-Skolkovo, and Vitaly Yermakov of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Mark Gongloff at mgongloff1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.