(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Cities in the Sun Belt South have been needing a more modern development model for a while. That's created tensions, both economically and politically, that have only accelerated during the past year's pandemic. My colleague Noah Smith wrote a column about this specific to Texas, but it's broader than any one state and it's useful to think about how we got to this point and why these issues are relevant in 2021 in a way they weren't a generation ago.

There's an institutional reluctance to pivot away from the Sun Belt model defined by low taxes and cheap land because of how successful it was for key constituencies for decades. Coming out of World War II, there was a scramble nationwide to build more housing in response to soldiers coming home from war and pent-up demand for family formation.

The combination of the automobile as the nation's now-dominant form of transportation and the passage of the Federal Highway Act of 1956 made building out the suburbs of less-populated southern states an irresistible growth model for politicians and economic development interests alike. If it required tax breaks and fewer regulations to lure jobs and people from northern states to accelerate the process, so be it.

A useful analogy for this dynamic might be the growth of manufacturing in China. When China began to trade with the West, it couldn't offer much in the way of skilled labor or technological know-how. What it could offer was cheap labor and low costs to lure foreign companies to build their factories in China, and that became its starting point.

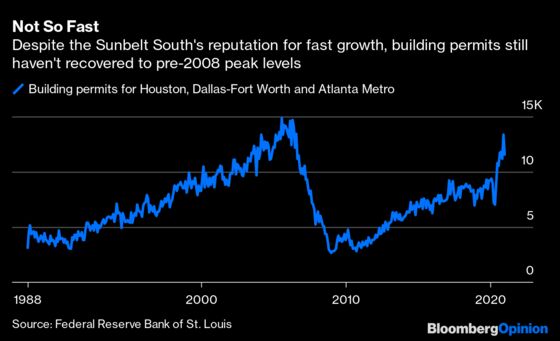

Over time, growth has reduced those advantages. Jobs and people moving to states like Texas and Georgia slowly bid up the price of land and labor. Ample spare capacity for land and transportation infrastructure — think six-lane highways — let sprawl be a growth outlet for decades, but over time congestion and distance from airports and job centers raised the cost of sprawl as well. The 2008 financial crisis arguably busted the sprawl model in the largest Sun Belt metros of Houston, Dallas and Atlanta, where until the onset of the pandemic single-family building permits had lapsed to 35% below the 2006 highs, despite those metros still having reputations for sprawl and fast growth.

Instead, what's defined the growth of these metros over the past decade has been a land-use equivalent of moving up the value chain in manufacturing — urban and suburban gentrification and the development of pockets of affluence. Following the housing bust, the depression in land prices combined with a rise in the cost of living for white-collar professionals in coastal metros. That created an opportunity to develop Sun Belt neighborhoods attractive to the upper-middle class looking for a lower cost of living — people like me, who moved to Atlanta a decade ago.

In cities, that's meant building luxury apartments catering to young, well-paid college-educated workers. For close-in suburbs with short commutes and good school districts, that's often meant tearing down or significantly rehabbing older homes to make them more desirable to families with six-figure incomes. And in both cities and suburbs it's meant bringing in many of the consumer and lifestyle amenities people in high-cost coastal cities are accustomed to — fancy coffee shops and restaurants, yoga studios, craft breweries and the like.

But readers in the Northeast and on the West Coast might not appreciate the extent to which these gentrifying suburban neighborhoods are no longer so affordable.

Here's a picture of a home in my neighborhood (see left) that's set to be torn down to make way for new construction. It's 1,000 square feet, built in 1945, and sits on a plot of land that's 0.3 acres. It sold in January for $400,000, and if recent neighborhood development patterns are any indication, it will likely make way for a new home that's at least 3,500 square feet and will price at over $1.1 million. Compared to Palo Alto, California, that might be affordable, but it's probably not the sort of thing people think about when they're talking about cheap Sun Belt housing.

Therein lies the tension. Well-educated people and their employers being drawn in by luxury apartments, fancy coffee shops and increasingly expensive suburban homes have expectations about infrastructure and public services that are incompatible with a late-20th century low-tax, low-service governance model. These are the types of people swinging the political makeup of these communities and states from Republicans to Democrats.

What's needed to maintain past growth momentum and meet the expectations of these new populations is a continued push up the value chain towards local economies based on knowledge work, with higher-paying jobs and college-educated workers. The specific services or investments needed to lure these types of jobs and workers will shift with the political winds — it might be a greater investment in schools and universal pre-K programs today, and transportation infrastructure tomorrow. It’s the same kind of policy arms race these communities have been accustomed to for decades, only with more services replacing low taxes as the policy lever.

For now, the most likely tweaks to the governance model will probably be incremental — stormwater improvements, sidewalk construction and other "complete streets" projects, modest increases to educational funding — simply because the votes aren't there to raise taxes enough for the kind of revenue needed for bigger changes.

But these tensions aren't going away. It's eventually going to require larger investments than current leaders and older voters are willing to make. Ultimately, the choice for these communities is to spend the money needed to stay competitive in the new arms race, or lose out to places that will.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.