The Market Needs to Be More Skeptical About T-Mobile-Sprint

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The U.S. Federal Communications Commission looks set to approve T-Mobile US Inc.’s long-sought merger with Sprint Corp., a major win for the companies. But if the FCC is playing good cop, there’s still a small chance that the Department of Justice takes on the role of bad cop. For that reason, T-Mobile should wait to hang its magenta party streamers until it gets a clearer signal that this really is a done deal.

T-Mobile announced on Monday that it will divest Sprint’s Boost Mobile pay-as-you-go business as part of a series of commitments it’s making to the FCC. The company also promised to offer 5G wireless network coverage to 97% of the U.S. population – and 85% of rural America – three years after the transaction closes, and that it won’t raise plan prices at least until then. In light of these assurances, “I believe that this transaction is in the public interest and intend to recommend to my colleagues that the FCC approve it,” Ajit Pai, the agency’s chairman, said in a statement.

From his lips to Makan Delrahim’s ears? Perhaps. Delrahim, the DOJ’s head of antitrust, hasn’t yet signaled where he stands on the $59 billion merger, though one might think that Pai wouldn’t give the nod unless he felt his DOJ counterpart was comfortable with the deal under the revised terms. The FCC would be taking on the duty of enforcing behavioral remedies, such as the price freeze, while the sale of Boost Mobile provides the kind of structural remedy that’s more palatable to Delrahim. That said, clearing the DOJ is still the bigger hurdle.

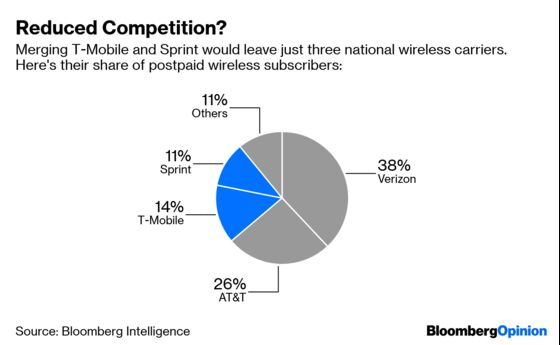

The DOJ’s decision may come down to the question that was at the center of this process from the onset: Will reducing the U.S. wireless market from four to three national carriers hurt competition? T-Mobile’s latest commitments don’t quite address this, unless antitrust regulators are predominantly concerned with the prepaid market. T-Mobile owns MetroPCS, while Sprint owns Boost Mobile and Virgin Mobile, all of which offer pay-as-you-go plans without contracts to lower-income consumers, those with bad credit and senior citizens. Without divestitures, T-Mobile and Sprint would have about a 40% combined share of that market, which I anticipated would be a problem. Selling Boost may at least appease state attorneys general and members of Congress who were worried about the impact on lower-income Americans.

But T-Mobile’s vow to not raise prices for three years is a fleeting protection for consumers in the context of a transaction that will fundamentally alter the wireless industry for years to come. If you don’t believe me, just look at the stock prices of T-Mobile and Sprint’s larger rivals: Verizon Communications Inc. jumped 2.7% on Monday morning, and AT&T Inc. rose 2%, as investors anticipate consolidation will restore pricing power. As I wrote in March, if regulators want proof that the merger will be beneficial to the wireless industry and not customers, there’s the fact that the companies’ shares have tended to rise when the deal’s prospects looked strong and fall when it appeared doomed.

It could be that T-Mobile’s argument that it can build a nationwide 5G network faster with help from Sprint’s spectrum is enough to ease concerns about competition, given the race the U.S. is perceived to be in against China to get to ultra-fast 5G service. However, rarely do antitrust cases work that way. The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index measurement of market concentration shows that the merger would far exceed the threshold that signals a problematic level of market power.

The most compelling argument for letting T-Mobile buy Sprint – even if it ranks lowest on regulators’ list of factors – is that Sprint’s business is in rough shape and getting worse. I outlined all the ways that’s true here, and Sprint’s results two weeks ago showed that it burned through nearly $2 billion of free cash flow in the 12 months through March. “Absent fresh capital, Sprint liquidity may wilt in the face of its obligations,” Stephen Flynn, a credit analyst for Bloomberg Intelligence, wrote in a note last week, adding that without the T-Mobile deal, Sprint may need to seek a cash injection from its controlling shareholder, Masayoshi Son’s SoftBank Group Corp.

After the FCC, it’s one down, and one to go. T-Mobile and Sprint’s shareholders have reason to be optimistic, but not overly confident. The same could be said for consumers.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Tara Lachapelle is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering deals, Berkshire Hathaway Inc., media and telecommunications. She previously wrote an M&A column for Bloomberg News.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.