Sydney’s Covid Outbreak Shouldn’t Be Fought on the Beaches

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- My hometown of Sydney is a divided city. Never more so than now, in the grip of a Covid-19 outbreak that’s overwhelmed its complacent sense of having escaped the pandemic.

In the east, suburbs close to the beach and the cooling breezes of the Pacific are the playgrounds of the affluent. Further from the ocean lies the hotter, more multicultural, lower-income expanse of western Sydney. The median house price in beachside Bondi, where the current outbreak first took hold, is nearly A$3.5 million ($2.5 million). In Oxley Park, 45 kilometers (28 miles) to its west and currently seeing some of the highest rates of infection, it’s around A$650,000.

That divide is making the challenges of stamping out the current pandemic worse. Across the whole of Sydney, masks are mandatory, non-essential retail is closed, and home visits and schools are off-limits except in unusual circumstances. However, in places the government has defined as “areas of concern” to the west and southwest, there are also curfews from 9 p.m. to 5 a.m., while children are only allowed outside for one hour of exercise a day.

“It’s really a fairness thing, that we’re not being treated the same as the rest of Sydney,” Khal Asfour, mayor of Canterbury-Bankstown, one of the areas of concern, told Australian Broadcasting Corp. radio Monday. “I’m not saying these restrictions shouldn’t be brought in. I’m saying they should be applied equally to everybody.”

In a city that’s also split by vaccination status, aggravating both sides of the social divide isn’t a good way to get people to pull together. The 41% of the adult population who’ve not had even a first dose are dependent on others’ compliance with lockdown measures to protect them. That group — younger, lower-income and often more socially disadvantaged — has predominated in the west, although the rapid rise of vaccine penetration in recent weeks has evened out the picture somewhat. Meanwhile, the 31.5% who are fully inoculated and make up a larger share in the east need the unvaccinated to get their shots if they want to escape the same constraints.

The fate of each group is in the hands of the other. If there's no sense of solidarity across the city, the temptation to flout the rules will keep growing as lockdown drags on.

The geographical divide has cemented an invidious caricature in the public imagination. In eastern Sydney, it’s often assumed that people in the west are ignoring lockdown measures altogether, after stories early in the current outbreak of extended families meeting up in spite of the restrictions — hence the willingness to deploy coercive measures such as curfews and troops to the streets to enforce the rules.

In the west, similarly, images of crowded beaches as the mercury climbed above 25 degrees Celsius (77 degrees Fahrenheit) on one of the last weekends of winter have led to a perception that more well-to-do suburbs are basking in a “mockdown,” while other areas suffer.

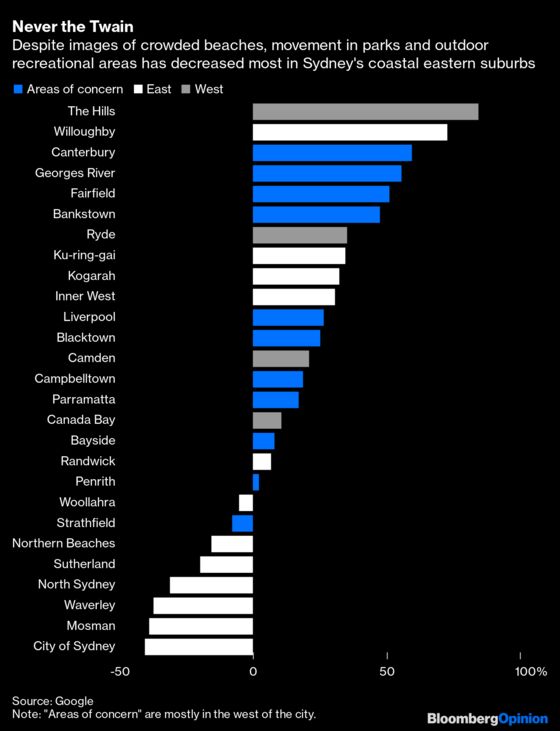

The truth is more nuanced. Just because someone is doing their socially distanced exercise at a beach, it doesn’t mean they’re flouting restrictions. Indeed, the numbers visiting parks and beaches are well down from typical levels, according to location data from Google.

In Waverley council area, home to Bondi, the numbers over the most recent seven-day period averaged 37% below the baseline, the biggest drop in the metropolitan area outside the office-dense central business district. The picture is similar in Mosman, Sutherland, Northern Beaches, and Woollahra, home to most of the rest of the Sydney’s coastline, with only Randwick council showing a small uptick in outdoor recreation.

Instead, it’s largely the west of the city where people have taken to the parks. Areas of concern regions such as Canterbury-Bankstown, Fairfield, and Georges River are seeing increases in outdoor activity of 50% or more. That’s hardly surprising. With abundant parks scattered through lower-density neighborhoods, people are doing much the same thing as they are in the east — getting out of their homes for a limited and cautious mental health break. If photographs of the Western Sydney Parklands aren’t causing consternation the way that images of Bondi have, that’s probably because fewer press photographers live nearby, and the landscape is less conducive to misleading long-lens “crowd” photography.

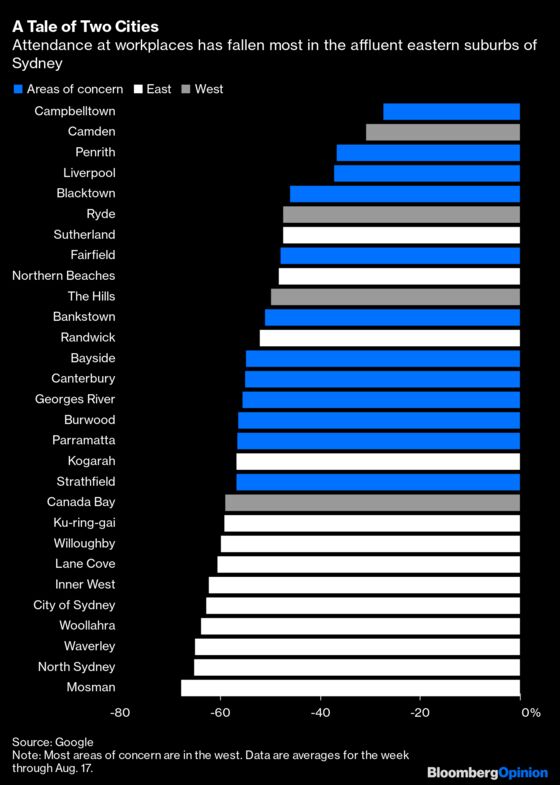

The true divide in the city isn’t really one of behavior. Most people east and west are doing their best to comply with a grinding lockdown for the sake of the common good. Instead, it’s one of economics. In the wealthy eastern suburbs, the number of people turning up at workplaces has fallen by 60% or more. Further west, the drop is often 40% or less. That’s because the sort of lower-paid, insecure retail, logistics or factory work that can’t be easily done from home is far more prevalent as you head west.

Despite the fact that a priority list of occupations at the front of the queue for vaccinations was drawn up last year, there’s still a drastic shortage of uptake that’s left many crucial workers exposed. Barely more than half of employees at aged-care facilities have had even a single vaccine dose in several regions on the fringes of Greater Sydney, according to federal government data. As recently as last week, the government was running a vaccination drive to get doses to key workers in hotspot council areas. That’s welcome, but it should have been completed months ago.

There’s danger in this moment. Compared to the complexity of ensuring the right people are at the front of the vaccine queue, it’s relatively cost-free to enforce curfews and outdoor movement restrictions. Such actions do little to contain the spread of the virus, though, and do much to degrade people’s mental health and willingness to comply with the rules. This lockdown could well stretch into November or beyond, and the government will need to draw on a deep pool of public goodwill to make it to the finish line. Each day that the outbreak plays on the insecurities of this divided city, that pool dwindles a little bit more.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.