(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The outcome of Sunday’s Swiss parliamentary election contains an important message. With the decline of traditional political parties built on comprehensive platforms, politics and government are increasingly at the mercy of the news cycle. If an issue suddenly captures voters’ hearts and minds, it can quickly displace the top worry from a year or a few years ago, and election results will change accordingly.

In Sunday’s vote, the anti-immigrant Swiss People’s Party (SVP) had its worst result since 1999. While it’s still the biggest party in parliament with 25.6% of the vote, the result was 3.8 percentage points less than in the previous election in 2015. By contrast, the Greens and the Green Liberals, two environmentalist parties, coasted to their best results ever, winning 13.2% and 7.8% respectively.

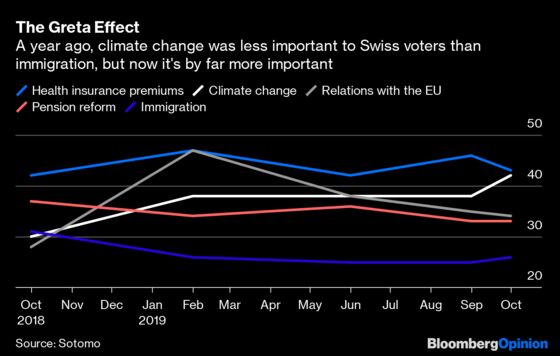

This won’t necessarily change the makeup of the federal government, which traditionally doesn’t exactly reflect election results. But regardless of whether Switzerland’s policies will change, the voting outcome directly reflects a recent change in the Swiss public’s priorities. In 2015, immigration was Swiss people’s top concern. Even as late as a year ago, immigration was more important to the Swiss than climate change.

Of course, this change in priorities didn’t come from any new data on the effects of climate change on Switzerland. The retreat of the alpine glaciers and the melting of snow caps are well-known. Back in 2011, the Swiss government sponsored a major report by the country’s leading scientific centers that laid out the likely scenarios. It’s not that some recent local natural disaster drove home the urgency. What’s changed is the activism of Greta Thunberg, the school strikes and the younger generation’s increasing concern. According to Swiss polls before the election, the green parties were attracting most of the young people who were voting for the first time.

The SVP doesn’t deny that climate change is taking place, but says it’s unclear to what extent human activity plays a role. Throughout the election campaign, the party militated against the “media hype” around climate science and called the 2015 Paris Agreement unrealistic. Clearly, this stance appeals to the national conservative party’s base. The SVP is right, in a sense, about the hype and has benefited from it, too. In 2015, when immigration was at the top of the media agenda because of the refugee crisis, the party won its biggest electoral victory in history. Fast forward to 2019 and it’s all about climate change.

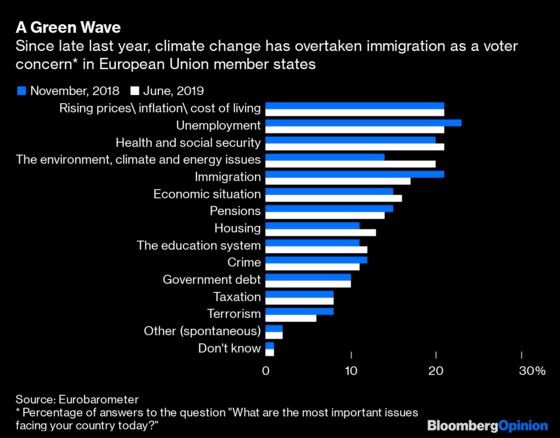

In many of Europe’s wealthy nations, voters’ concerns have evolved in a similar way. According to the latest Eurobarometer survey, climate change is the most important issue for voters in Germany, Denmark, the Netherlands, Austria and Sweden; in France, it’s overshadowed only by unemployment. Across the 28-member European Union climate change and the environment have now overtaken economic and social concerns as top worries. This wasn’t the case last year.

If indeed this change is a function of “media hype” — or, more neutrally, the attention that different issues get in the public discussion going on in the media, on social networks, in schools, on the streets and around the dinner table at home — then traditional center-left and center-right parties’ recent problems have a logical explanation. They are unaccustomed to running single-issue campaigns. They don’t always know how to take ownership of the day’s agenda. They are not specialized enough to benefit from changes in the volatile electorate’s moods.

This is the age of the narrowest possible segmentation in what’s called hyperspecialization. Just as people burrow down increasingly specialized rabbit holes at work, they’re finding comfort in politicians with focused agendas. At the same time, people choose from an ever-growing multitude of music styles and news sources, while listening to advice from individual influencers rather than institutions. In politics, the trend is manifesting itself as increasing fragmentation. Waves of “hype” determine the behavior of swing voters, who are not part of any political force’s base. These voters don’t want balanced portfolios of policies, but rather a mastery of specific issues that appear topical today.

Traditional centrist parties’ future in such a world doesn’t have to be bleak. Single-issue parties need allies to work with them on the rest of the issues that come up in governing nations — and that remain important to voters regardless of the top item on today’s agenda. In Switzerland, and likely in other wealthy nations, the center-left and center-right parties will vie for the opportunity to work with the surging environmental parties, who, unlike the far right, are not perceived as toxic by centrist voters.

The question is whether the green parties can keep climate change as topical as it is today. For Thunberg and other climate activists, that’s a matter of keeping the young actively engaged without slipping into the irrelevance of generic protest that disturbs the peace but offers no true alternative to the status quo. Another wave of refugees sweeping over Europe or a sharp economic downturn may make it hard for environmentalists’ to keep fickle voters’ attention.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Melissa Pozsgay at mpozsgay@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.