The U.K. Bank Tax Cut That Won’t Make Anyone Happy

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Britain is getting a bit desperate about banking. U.K. Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak will slash a special tax charged on bank profits in this month’s budget. He hopes it will ease tensions with grumpy industry executives. But Sunak should expect to take political heat from the change because the cut is being announced at the same time as he’s reduced benefit payments for the poorest and lifted the welfare-funding National Insurance tax on income for everyone.

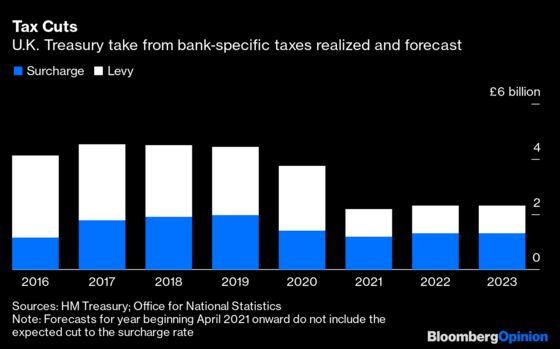

On top of that, banks won’t really benefit. The planned 5 percentage point cut to the surcharge rate — as reported by the Financial Times — will be more than netted off by a 6 percentage point rise in headline corporate tax rates that was announced in March. From 2023, when both changes take effect, banks will still face a higher headline tax rate than they do today — and hardly any advantage compared with taxes they’d pay in the U.S. or parts of Europe.

So why attract extra headlines to this tax cut now?

The Conservatives needs to patch up relations with the City of London — and this is one of the only tools Sunak has.

Tory governments since the Brexit vote in 2016 have treated Britain’s finance industry with disdain, leaving it to find its own way around the trade barriers for services raised by the U.K.’s departure from Europe’s single market. Prime Minister Boris Johnson has been more interested in fighting the French over fishing rights.

There’s been a long-held and arrogant belief in the permanence of London’s gilded position in the financial world. So much so that politicians were more than willing to give bankers — emblems of metropolitan privilege — a good kick as they tried to win votes in parts of the the U.K. far from London.

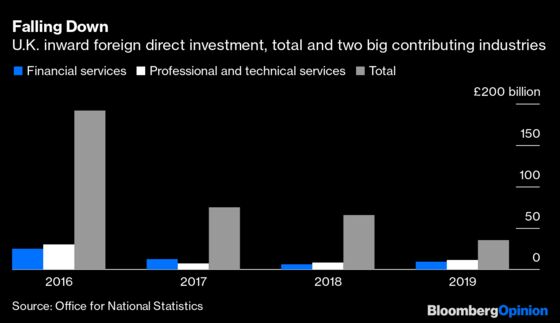

But that faith in London’s role is now giving way to fear. Foreign direct investment into the U.K. has fallen off a cliff since 2016, with finance and other professional services leading the decline. The government is also getting antsy about bankers moving to Paris and Frankfurt, where they are better positioned to serve clients they can no longer satisfy from London. According to research firm New Financial, about 550 billion euros (about $640 billion) of bank assets have already been moved out of the U.K. into the EU to comply with regulators’ wishes there.

Indeed, regulation is far more important than lowered taxes when it comes to the operation of banking and markets. If financiers want to deal with Europe, they have to meet Europe’s rules – and only Brussels can judge whether institutions operating out of London are following those rules.

Sunak and Johnson have limited power to make any of that easier for bankers. And turning London into “Singapore-on-Thames” — the dream of many Tories — isn’t going to happen while there is still a chance that Britain could be granted regulatory equivalence by Brussels as part of post-Brexit negotiations. Even ditching the EU’s cap on banker bonuses can’t be done while there remains any hope that London could win eased conditions for the trade in financial services in Europe.

The biggest benefit that banks are getting from the U.K. right now isn’t even a gift from Sunak. It’s part of a schedule set up by then-Chancellor George Osborne in the wake of the global financial crisis. This year, the post-2008 tax on the size of bank balance sheets will shrink in scope to cover only assets held in Britain. It used to cover global assets of U.K.-headquartered banks, as well as some non-U.K. banks that operated in Britain.

Barclays Plc results Thursday illustrate the size of the potential savings: Last year its international business paid 240 million pounds ($331.4 million) on the levy, which should disappear due to the scheduled cut. In the meantime, total income from the levy to Britain’s Treasury is set to drop to 1 billion pounds for 2021-2022, from 2.34 billion pounds the previous year.

So what’s the best thing Sunak and Johnson might do for the City and for the Treasury? Go back to Brussels and work on a deal for financial services.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Paul J. Davies is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering banking and finance. He previously worked for the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.