(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Bitcoin has a carbon problem. Producing Bitcoins and keeping them secure relies too much on cheap coal power, especially in China. This adds to the world’s actual greenhouse gas emissions in exchange for a virtual thing of debatable benefit. So promoters are touting various ways to give Bitcoin a green sheen.

Funnily enough, the latest one involves coal. Actually, coal refuse, which is as bad as it sounds. Greg Beard, who used to head up Apollo Global Management Inc.’s natural resources business, is now chief executive of a new venture called Stronghold Digital Mining. Stronghold aims to mine coal that was already mined in order to mine Bitcoin and thereby make it green. Got that?

An estimated 220 million tons of coal refuse left over from decades of mining sits in giant piles dotting Pennsylvania. Apart from the awful aesthetics, rainfall percolates through them, leaching metals and other undesirables into rivers and streams. The piles also occasionally spark fires. Some ways to address the problem include removing the waste or covering the piles with hardy vegetation like beach grass to encourage natural reclamation.

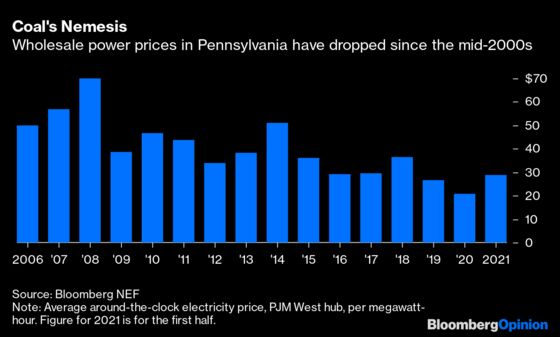

Another way is to burn the waste coal to produce electricity. More than a dozen specialized plants were built in the 1980s and 1990s and are estimated to have burned through roughly half the pile since then. This worked well when (a) coal power was competitive and (b) carbon emissions were not taken seriously. Neither of those things hold today. Coal plants have been squeezed as cheaper natural gas and renewables pull down power prices.

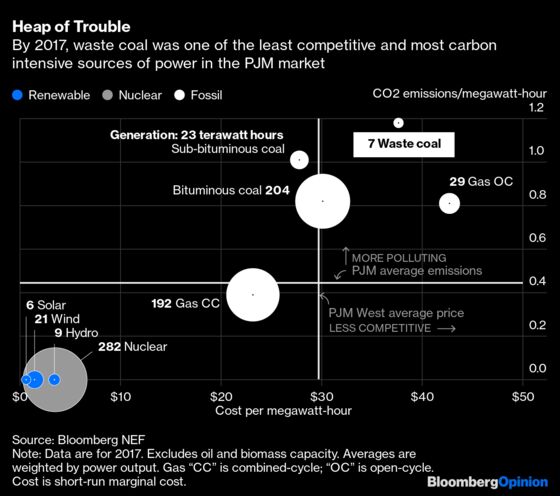

As you might imagine, waste coal is even less competitive than regular coal yet also more carbon intensive. The chart below shows the marginal cost and emissions intensity of the major types of plant operating on the PJM grid in 2017, the last year for which Bloomberg NEF has this data for all the waste-coal facilities.

Waste-coal plants are subsidized by the state, and some even got a special exemption from federal air-quality rules under the Trump administration. But these don’t offset the fall in power prices. Indeed, lobbyists have pushed not merely for higher state subsidies but also a federal program to keep the plants going.

But what if you could find a use for their power tied to an energy-intensive and potentially lucrative thing like, say, Bitcoin?

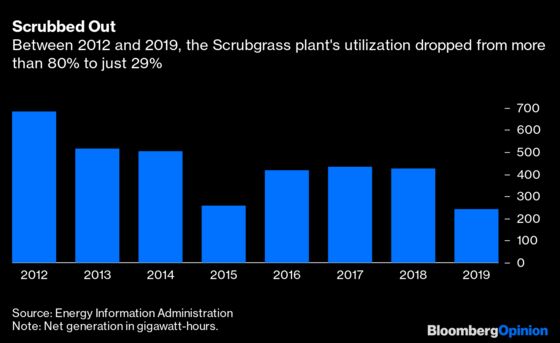

This is what Stronghold aims to do. Its first facility, the Scrubgrass plant, began operating in 1993 and is about a 90-minute drive north of Pittsburgh. Output has dropped by almost two thirds since 2012, according to data from the Energy Information Administration.

Stronghold styles itself as “ESG-friendly” because Scrubgrass helps to clear waste coal and, when burning it, removes much of several types of associated pollutants such as mercury (as coal-fired plants are required to do in general). One pollutant conspicuous by its absence in the marketing: carbon dioxide.

It’s unclear how hard Stronghold will run Scrubgrass; the company didn’t respond to several requests for comment. But the economics of Bitcoin mining demand continuous computation. Say utilization rose back to 80%, roughly 2012 levels. Using average emissions intensity for the five years through 2019, Scrubgrass might emit about 855,000 tons of carbon dioxide a year . By way of comparison, a gas-fired plant of the same size would emit less than a third of that.

Those emissions, even if unpriced, represent a cost to society. At the latest auction price of almost $8 a ton for the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative that Pennsylvania’s governor seeks to join, the implied cost would be almost $7 million a year . Small in absolute terms, it would still add another $10 to the plant’s already uncompetitive marginal cost per megawatt hour, estimated by Bloomberg NEF to be almost $50. That auction price doesn’t reflect the actual cost of abating a ton of carbon dioxide. Priced at, say, $30 a ton, the plant’s implied all-in cost per megawatt-hour would be more like $90, making it utterly uncompetitive.

Scrubgrass is a micro-example of the broader problem with burning waste coal. Pennsylvania’s waste-coal fleet operated at 59% of capacity in 2012. Operating at that level now, it would emit nine million tons a year, adding up to $270 million of cost at $30 per ton. That figure happens to be slightly higher than the cost of removing and disposing of Pennylvania’s waste-coal piles, as estimated by the waste-coal power industry’s own lobbyists .

Pennsylvania is grappling with real trade-offs around water and air pollution, local employment and climate change. On balance, it believes the benefits of burning waste coal outweigh the drawbacks. Yet the message from the wholesale power market is that the old method of dealing with reclamation costs no longer works. Indeed, throw in carbon costs, and it probably never did. The resort to Bitcoin is the tell. At this point, Pennsylvania simply burning its way through the problem is untenable; even at the faster pace of 2012, those plants would be churning out emissions into the 2040s.

As for Stronghold, the idea that burning coal refuse even more carbon-intensive than regular coal power somehow makes it an ESG star is financial spin raised to the level of tragicomedy. The great irony here is that only three months ago, Bitcoin afficionados such as Cathie Wood, Jack Dorsey and Elon Musk were pushing the notion that cryptocurrency could actually encourage more investment in the renewable power of the future. Stronghold’s approach is the exact opposite: capitalizing on the Bitcoin craze by reviving the polluting technologies of the past.

-- With graphics by Elaine He

Scrubgrass' average emissions intensity for 2015-19 was 1.29 tons per megawatt-hour (Source: Energy Information Administration).

This is theoretical because not only is Pennsylvania's participation in the RGGI contested by its legislature, there is a carve out for the waste coal plants to shield them from the cost of their carbon emissions.

"Replicating the annual removal of 8 million tons of refuse and remediation of 240 acres would cost the state $93 million annually under the most favorable conditions, and $267 million annually including typical disposal costs."The Coal Refuse Reclamation to Energy Industry - A Public Benefit In Jeopardy(Anthracite Region Independent Power ProducersAssociation, June 2019).

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.