(Bloomberg Opinion) -- U.S. stocks led the way on Tuesday in the biggest rally for global equities since the depths of the financial crisis in October 2008, with the MSCI All-Country World Index surging 8.39% in late trading. No one is ready to say the rebound is the start a sustained rally; history shows that in times of crisis, markets experience multiple false starts. So rather than the beginning of the end, it may be more like the end of the beginning.

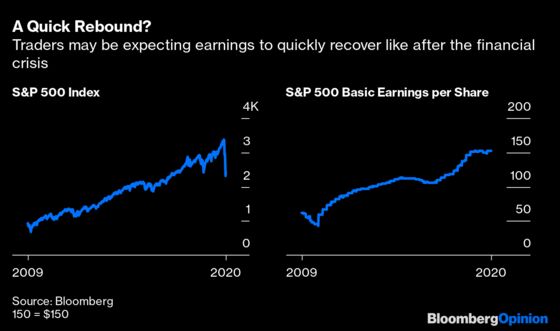

And yet, although stocks have experienced unprecedented volatility in recent weeks, plummeting into the fastest bear market in history, one thing is becoming clear: Investors are optimistic that the earnings power of U.S. companies has only been temporarily impaired. At Monday’s close of 2,237, the S&P 500 Index was trading at 19 times the benchmark’s average earnings per share of $122 over the past decade, according to DataTrek Research. It’s a safe bet that earnings won’t meet that average in 2020 given the steep contractions in the economy being projected, “but markets think we’ll get there in the next year or the year after,” DataTrek co-founder Nicholas Colas wrote in a research note. That’s a tremendous vote of confidence in America, but is it realistic? After the financial crisis, Colas notes that it took just 12 months, or until the first quarter of 2010, for earnings to return to their pre-crisis normalized levels. It took another 18 months for earnings to reach a new highs.

The economic data that will trickle out in coming months will surely show a lot of pain and questions of how quickly corporate America can rebound. Some Wall Street firms are predicting the economy will likely contract by 30% or more in the second quarter. But the recent sell-off in markets has happened at double the speed of what we saw during the financial crisis. Given that, is it crazy to think the recovery could come faster? Investors don’t seem to think so.

SURVIVAL OF THE FITTEST CORPORATE BONDS

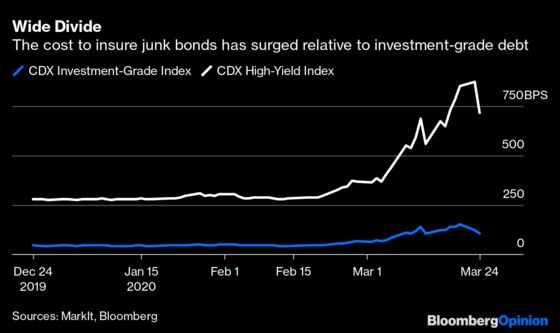

A key part of the Federal Reserve’s latest efforts to keep the financial system afloat is to buy corporate bonds. More specifically, the central bank will only buy investment-grade bonds maturing in five years or less, as well as exchange-traded funds that buy such securities. Bonds rated below investment grade, or junk, are out of luck. This has naturally resulted in a clear bifurcation in the corporate bond market between the “haves” and the “have-nots.” The cost to insure investment-grade corporate bonds against default has fallen to about its lowest level in more than two weeks. The cost to do the same with junk bonds is only back to where it was late last week, which is to say at levels that predict an elevated level of defaults on the order of about 10% or so that we saw in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. In some ways, this isn’t a bad thing, as it should finally prod borrowers to clean up their balance sheets and cut their debt, which has hardly been an incentive in recent years. But the gap in yields between investment-grade and junk bonds has blown out to almost 7 percentage points in recent weeks from less than 3 percentage points.

THE DOLLAR TAKES A NEEDED BREATHER

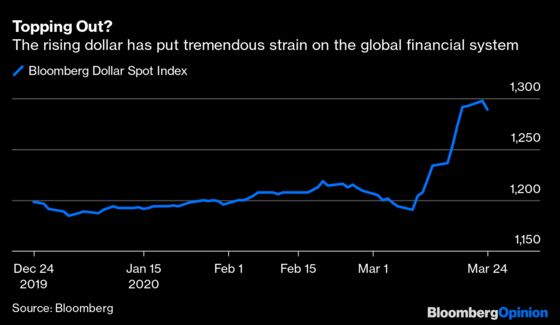

Of all the moves by the Fed over the last week, perhaps the most underappreciated has been efforts to ease a run on the dollar, stemming a rally that further threatened to upend the global financial system. What the Fed did was provide foreign-exchange swap lines with central banks in both developed and emerging markets, offering dollars in exchange for their currencies. Issuers in developing countries have borrowed trillions of dollar-denominated debt, and the greenback’s rise means it’s much more expensive for them to make interest payments or refinance. The Institute of International Finance estimates that emerging-market borrowers have $8.3 trillion of foreign-currency debt, the bulk of it in dollars, up by more than $4 trillion from a decade ago. The Bloomberg Dollar Spot Index surged 8.44% between March 9 and March 19, but has been little changed since, including dropping as much as 1.51% on Tuesday in what was its biggest intraday decline since February 2016. “Markets are going to start feeling the full tsunami of liquidity the Fed is providing now,” Nathan Sheets, head of macroeconomic research at PGIM Fixed Income, told Bloomberg News.

GOLD IS ACTING ODD AGAIN

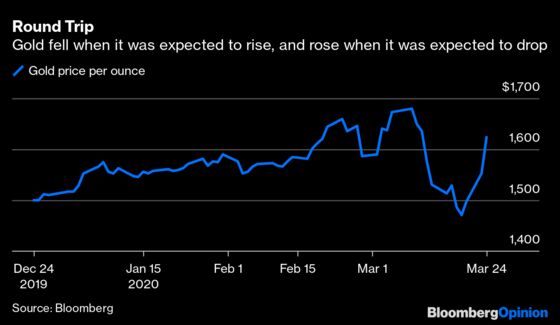

For the most part, markets have behaved as one would expect in times of crisis. Investors fled riskier assets such as equities, commodities and credit, and loaded up on cash, U.S. Treasuries, the dollar, Swiss franc and Japanese yen. The one exception has been gold. The precious metal sold off hard as the coronavirus pandemic spread around the world earlier this month, and in recent days has rebounded even though there have been signs of optimism. This isn’t how gold, known as a haven, is supposed to act. But there are sensible explanations. Gold’s decline from about $1,680 an ounce on March 9 to $1,471 on March 19 was likely the result of selling by finance authorities and central banks, which had loaded up on the precious metal throughout 2019 to raise cash. The rebound over the past three days to $1,623 on Tuesday is harder to explain, but is likely tied to physical trading routes being choked off. At issue is whether there will be enough gold available to deliver against futures contracts, with metals refiners shutting and efforts to contain the virus halting planes, according to Bloomberg News’s Jack Farchy and Justina Vasquez. “This isn’t anything that we’ve seen in a generation because refiners never had to shut down – not in war, not in the great financial crisis, not in natural disasters,” said Tai Wong, the head of metals derivatives trading at BMO Capital Markets.

TEA LEAVES

The Mortgage Bankers Association of America releases data on the volume of loans for home purchases and refinancings every Wednesday. And although it would be logical to think that the collapse in Treasury yields, which help determine mortgage rates, would be a boon for homeowners looking to refinance, that hasn’t exactly been the case. Yes, refinancings are up, but so are mortgage rates. The average rate on a 30-year mortgage has jumped to 3.65%, the highest since January, from 3.29% earlier this month, according to Freddie Mac. One reason for this is the disruptions that we have seen in the market for mortgage bonds, which also help set home-loan rates. Yields on those securities have jumped as investors both sell the most-liquid mortgage bonds in an attempt to raise cash and as those bonds backed by riskier borrowers drop on concern for the potential of a spike in consumer defaults. The government is taking steps to alleviate pressures on consumers, but until that happens, mortgage rates are likely to remain elevated relative to what they would normally be.

DON’T MISS

$25 Trillion of Derivatives Exposure We Can't Cover: Shuli Ren

Matt Levine's Money Stuff: Now There’s a Mortgage Crisis Too

Fallen Angels Are Coming. Fed Can't Save Them: Brian Chappatta

Trump Would Hurt Economy With Restart Effort: Michael R. Strain

How a Risk Manager Thinks About Personal Finance: Aaron Brown

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Robert Burgess is an editor for Bloomberg Opinion. He is the former global executive editor in charge of financial markets for Bloomberg News. As managing editor, he led the company’s news coverage of credit markets during the global financial crisis.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.