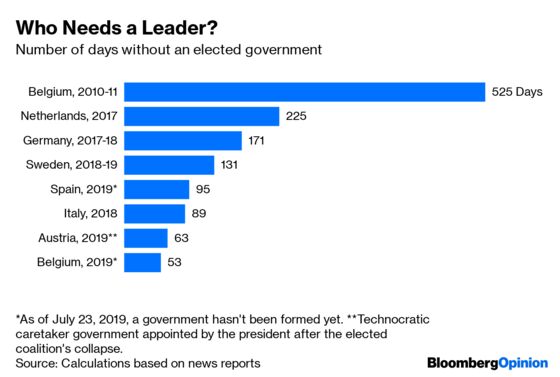

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- This week, Spain may finally get a government based on the results of its April parliamentary election. If it doesn’t, there’s likely to be a fourth election in as many years. Spain joins the growing ranks of countries run for extended periods by technocrats rather than politicians, and it appears to be doing fine – like most of the others in this group.

Spain has been without an elected government since April 28; Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez’s Socialist Party, which won a plurality, has been holding coalition talks, primarily with the leftist party Podemos, which supports a nonbinding independence vote in Catalonia. Now that Podemos leader Pablo Iglesias has dropped his demands for a top cabinet post, an alliance looks likely, but the coalition still won’t have a majority in parliament. This will make it difficult for Sanchez to govern without the support of Catalan separatist parties, which caused his previous cabinet to collapse. In other words, even if Sanchez succeeds in forming a cabinet, it won’t have a mandate for any kind of sweeping policy changes, but mostly just for the day-to-day running of the country.

That’s actually fine. Throughout the recent politically turbulent period, which started with the 2015 general election, Spain has had weak minority and caretaker governments. Meanwhile, unemployment dropped from 21% to less than 15%, the economy grew by more than 2.5% a year, pretty fast by euro-area standards, and the 10-year government bond yield dropped from 1.8% to about 0.4%. If Sanchez fails at forming the government, no economic cataclysm is likely to ensue; none occurred in a number of other countries that recently have gone for months without an elected government. In fact, it’s impossible to detect any change in economic trends during the protracted periods without a political cabinet.

In most cases, it takes a long time to form a government after an inconclusive election – an outcome that has become especially frequent in recent years because of growing political fragmentation and the decline of traditional centrist party machines. But there are other scenarios, too – for example, the Austrian one this year. After the elected coalition government collapsed because of a scandal over a clandestine recording, the country's president appointed a technocratic, nonpolitical caretaker candidate.

Or consider the cases of the U.S. and the U.K. Technically, they have elected governments, but the high churn rate among top officials essentially leaves the countries without functioning political cabinets.

In Theresa May’s government in the U.K., according to Jessica Adolino from James Madison University, there were 45 resignations between June 12, 2017, and April 3, 2019; many more have occurred since, making an exact count rather pointless. The Trump cabinet, according to the Brookings Institution, has seen 48 out of 65 “A Team” positions turn over.

The U.S. economy, meanwhile, hasn’t skipped a beat; the U.K. one has experienced a little turbulence, but largely because of the risks of Brexit rather than the lack of a stable government.

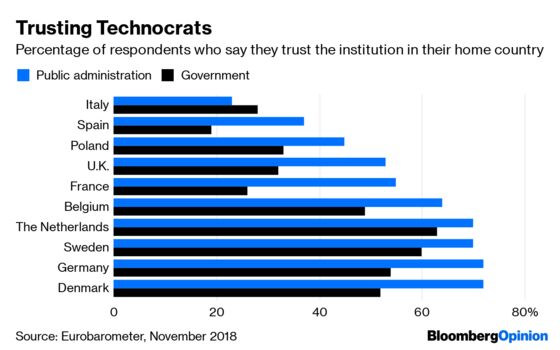

The politically unstable Western nations owe this ability to exist without elected governments, or with dysfunctional ones, to the strength of their institutions. While politicians squabble and voters can’t decide whom they want to run the country, the government is run by civil service professionals, and even when the political authorities show little respect for them – as in Trump’s case – they are competent enough to keep the wheels turning.

Citizens appear to appreciate this: In most European countries, they have more trust for the public administration (or, put differently, the civil service) than for the government.

Some political scientists argue that the professional civil servants depend on political appointees for career advancement and have therefore become more politicized in recent years. But the degree of civil service politicization doesn’t appear to affect how well they run their countries during long periods of political turmoil. For example, in Germany relatively many civil servants are replaced when political power changes; in the Netherlands, relatively few. Both countries, however, avoided economic trouble during their recent protracted coalition talks because competence remains the highest virtue in their civil services.

Political governments’ job is to make bold decisions and effect policy change. But one could argue that in the case of generally well-run Western nations, such change simply isn’t necessary as often as elections, especially snap ones, are held. Bold political leadership isn’t just overrated – in many cases election winners are no better at providing it than the cautious civil servants who have their back.

The problem, of course, is that the increasing political fragmentation and reliance on technocratic government create a vicious circle. As nations are increasingly run by unelected bureaucracies backing up weak and caretaker governments, there’s increasing demand for political renewal, which causes more fragmentation, and so on. On the one hand, strong civil services are a barrier against populist excess. On the other hand, powerful technocracies irritate voters who doubt whether their voices are heard.

Spain’s economy may be improving despite the string of weak governments, but the unusually strong showing of the pro-direct democracy, far-right Vox party in the last election – more than 10% support and the first parliamentary seats for such a force since Spain has been a democracy – could be a signal that some voters are getting fed up with management instead of political government.

There are only two paths out of the vicious circle, and both require an improved performance from centrist forces. One is for them to get better at forming strong, well-functioning coalitions. For example, Sanchez would have a majority in parliament if he made a deal with center-right Ciudadanos – but policy differences and individual ambitions have made such an alliance impossible, even though it was the preferred outcome for many Spanish businesses and investors.

The other option is even more difficult. It’s for centrist parties to get their act together, win back voters’ trust and start winning elections outright.

In any other scenario, strong institutions someday may not be able to protect even prosperous nations from bad governance: They could be dismantled by winning populist forces that dislike and distrust the “deep state.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Tobin Harshaw at tharshaw@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.