How One Country’s Ban Saved Short Sellers From Themselves

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- During the March selloff, markets sensitive to global business cycles scrambled to ban short selling. When I wrote an article agreeing with South Korea’s six-month ban, I got quite a bit of push-back. “Short-sellers aren’t driving markets down, it’s long sellers exiting their positions,” wrote one reader, who normally likes my columns.

Our savvy investor was right. Such a ban can hurt sentiments. Non-Korean long-short funds, for instance, need to hedge, or they can’t be in that country’s marketplace at all. But Covid-19 has thrown up all sorts of weird surprises. In fact, these days, it’s almost better not to be tempted with too many options. Sit tight or stay out; otherwise, you might just find yourself busy short covering.

All of a sudden, South Korea has become a shining star as we enter a world that is beginning to roll out Covid-19 vaccines. In November, foreigners poured over $4.4 billion into the Kospi Index, the highest monthly inflow in seven years and a sharp reversal from pessimism earlier in the year. They crowded into tech blue chips from Samsung Electronics Co. to SK Hynix. Last month, Korea’s semiconductor exports grew 16.4%, the highest in two years. In the last five days, the won jumped 2.3%, the most among major Asian currencies.

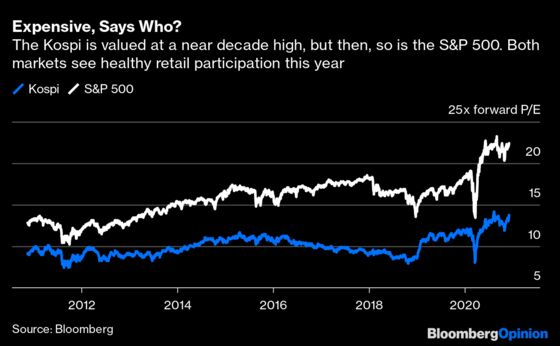

By now, short sellers are itching, because the Kospi has become expensive. It’s now trading at almost 14 times 12-month forward earnings, a near decade high, even as sell-side analysts pencil in an aggressive 45% earnings growth in 2021. Is the Kospi due for a correction? (CHART)

In normal times, earnings analysis and historical charts matter. But we live in the Covid-19 era, where day traders, who tend to use online brokerages such as Robinhood Markets Inc., are the price setters.

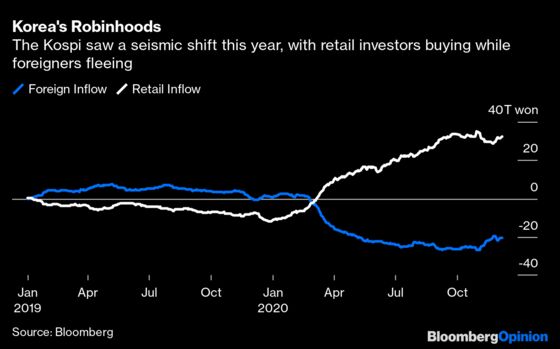

The Kospi has its own Robinhoods. Day trading Koreans, who dabbled in cryptocurrencies and all sorts of structured products in the past, are frantically buying domestic stocks this year. They single-handedly pulled the Kospi out of its March selloff, even as foreigners, who own over one-third of the market, fled. Sure, there was a bit of profit-taking in early November, but they came back. (CHART)

So who’s to say what the Kospi’s fair value is? Day traders are creating the market’s most seismic shift in a decade. They rescued the Kospi out of steep conglomerate discounts, and gave life to trading turnover. In three years, margin loan balance almost doubled to 8.7 trillion won, according to CLSA Ltd. That enthusiasm might just stay, especially if President Moon Jae-in continues to rein in residential property investments.

I get it. After dizzying rallies, what’s locally known as the seven princesses — two biotechs, two electric-vehicle battery makers, and three Internet companies — could be ripe for short selling, especially since their global peers, from the Big Tech to EV makers such as China’s NIO Inc. and XPeng Inc, are seeing a mini-correction. However, until we understand the new retail dynamics in a specific country, perhaps it’s better that short selling not be in our toolbox at all.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.