(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It takes chutzpah to list the company behind the British private members club Soho House when many of its trendy outposts were recently closed due to the pandemic and the debt-laden group has been bleeding cash.

Asking for money from new shareholders without granting equal voting rights takes particular gumption. The co-owners — billionaire Ron Burkle’s Yucaipa Companies LLC, entrepreneur Richard Caring and founder and Chief Executive Officer Nick Jones — plan to receive Class B stock that grants them ten votes per share, according to a prospectus published on Monday. This will allow them to continue to exercise majority voting power after the New York listing, meaning they retain a veto over key decisions and control board appointments.

Dual-class share structures have become common in the U.S., especially among tech startups (as well as more mature companies like Soho House that aspire to be valued like one).

Perhaps it’s to be expected that a company that prides itself on exclusivity and good taste doesn’t intend to become a bastion of shareholder democracy. Membership Collective Group Inc., as the hospitality company has been renamed, has attracted almost 120,000 members by being acutely responsive to its members’ wishes. Some of them are at least being invited to participate in the offering.

However, unlike the fashion-conscious creative types desperate to get on one of Soho House’s lengthy waiting lists, institutional investors can be far pickier in how they deploy their cash. They’re in a position to drive a hard bargain.

MCG will reportedly seek a $3 billion valuation when it lists on the New York Stock Exchange in the coming weeks.

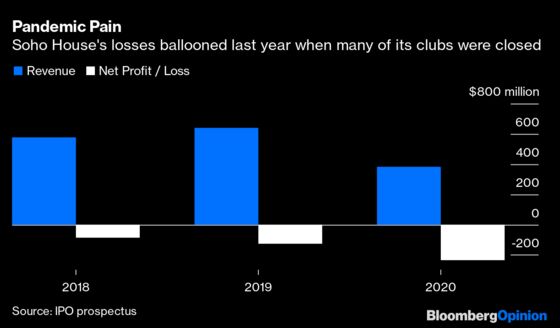

That’s punchy considering it has never made an annual profit in its 25-year history. It posted a $235 million loss last year when revenues collapsed 40% — members mostly kept paying their dues but restaurant takings fell sharply.

In the meme-stock era, it’s become unfashionable to discuss financial fundamentals. That’s not the only timing advantage Soho House gets by going public now.

Its clubs, hotel rooms, spas and restaurants should benefit from post-pandemic “revenge spending” and its co-working spaces from the shift to flexible working. Along with a slate of new club openings, Soho House believes its “SH.APP,” the cringe-inducing name for its revamped digital app, should drive further growth by helping new digital-only members access bespoke content and connect with each other.

The group also cut costs during the pandemic. It has switched to a capital-light expansion approach in which landlords shoulder many of the costs for refurbishing buildings in return for higher rent. By using part of the IPO proceeds to pay down debt, the bottom line and balance sheet should improve.

But beneath the glamorous veneer, the company has been reliant on lenders. A March refinancing replaced a big debt facility provided by Permira Credit with another one funded by Goldman Sachs Group Inc. (Goldman is among a slate of top-tier banks underwriting the offering.)

The company acknowledges that if lockdowns or pandemic restrictions were to return and impair its ability to reopen as planned, “we may need additional financing.”

Given these limitations and risks, new shareholders should be able to expect the red carpet treatment. Instead, by limiting their voting rights, they’re being asked to defer to the wisdom of the current owners. As ever, Soho House believes it’s a cut above.

This is a discounted figure. The undiscounted lease liability is more than $2 billion.

Mostly due to the settlement of Permira's accrued interest

The old Permira facility had a floating rate of Libor + 7%. As part of the refinancing, Goldman affiliates purchased $175 million of preference shares, which will convert to common equity following the IPO.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies. He previously worked for the Financial Times.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.