Slovakia Shows That Hate Speech Is Bad, Banning It Is Worse

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Three months before Slovakia’s national election, Robert Fico, the nation’s former three-term prime minister and current leader of the ruling party, has been charged with hate speech, an offense that can potentially land him in prison for five years. Though what he said is certainly reprehensible, the case shows why censoring political speech, as many European countries routinely do, isn’t a great idea.

The story began in October 2016, when Milan Mazurek, a nationalist member of the Slovak parliament, said in a radio interview that the government shouldn’t be funding housing for the country’s Roma minority — “people who have never done anything for our nation or our state, but on the contrary, chose to live in an asocial way and suck on our social system.” Both Mazurek and the radio station later were fined, and the legislator lost his parliamentary mandate. Slovakia’s Supreme Court made the final decision in the case in September 2019.

Soon afterward, Fico posted a video on Facebook, in which he said: “Milan Mazurek only said what nearly the whole nation thinks. If you punish someone for telling the truth, you make him a national hero.” That’s what landed him in trouble with the National Criminal Agency, which charged him on Thursday with disparaging nation, race and belief and with inciting ethnic hatred.

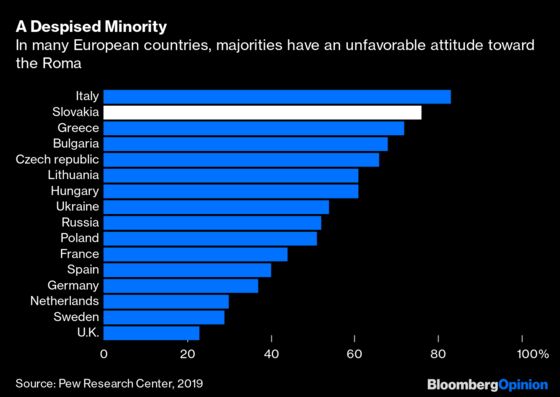

The Roma, often described as Europe’s largest ethnic minority, are highly visible in Slovakia. They make up just 2% of the country’s population, but they largely live in segregated, often miserable settlements on the edge of villages or towns. An attempt to map them in 2016 found 804 such settlements. Few serious attempts at desegregation have been made: They are politically unpopular. Slovakia has one of the most anti-Roma populations in Europe.

So in a way, what Fico said about Mazurek’s conviction making nationalist ideas even more popular makes sense — even if describing the ex-legislator’s word as “the truth” was unworthy of a mainstream European politician who has headed his country’s government for a total of 10 years. The Roma, after all, were an ethnic group the Nazis persecuted with an ardor matched only by that of the Holocaust.

Yet Fico, as is his wont, couldn’t resist making a populist statement as his party, Smer, battles to retain its lead ahead of the election, set for Feb. 29 of next year.

Though Fico is probably the most senior and high-profile political figure in Europe to be charged with inciting ethnic hate, European countries don’t shy away from using their hate speech laws against politicians. Far-right German politician Lutz Bachmann, founder of the anti-Islamic Pegida movement that staged huge demonstrations in eastern Germany, was fined 9,600 euros in 2016 for calling refugees from the Middle East “cattle,” “filth” and “scum.”

French far-right leader Marine Le Pen spent years fighting criminal charges after her 2010 comment comparing Muslims praying in the streets to Nazi occupiers; she was acquitted in 2015, but now another trial is pending for her for posting gruesome images of Islamic State victims on Twitter in 2015, after a series of terror attacks in Paris. Lesser activists are regularly charged and sometimes sentenced.

But Fico’s case, coming as it does in the heat of an election campaign, shows the potential for hate speech laws to be abused for political ends — something Fico himself, unsurprisingly, raised in a Facebook post on Friday. He claimed he was charged for “expressing an opinion” and accused the opposition of using the charges to attack his party, which stood firmly behind him.

Thanks in large part to Smer’s long rule, Slovakia’s democratic institutions are hardly a shining example to the rest of Europe. Last year, Fico was forced to resign as prime minister after the murder of an investigative journalist and his fiance sparked mass protests. A wealthy businessman has been charged with ordering the killings.

Corruption, even state capture, has emerged as a major problem, resulting in the election of anti-graft activist Zuzana Caputova to the country’s relatively weak presidency this year. The party behind the Caputova phenomenon, Progressive Slovakia, is the second most popular in the country behind Smer.

But if it’s time for a change of ruling party, it shouldn’t come thanks to the prosecution of Smer’s leader for something he said. The charges could even backfire, given the Slovak public’s distrust of the Roma and the growing popularity of nationalist parties.

It would be far better for the downtrodden minority and the country as a whole if the opposition could convincingly argue the case for a stronger and smarter integration effort and present a contrast to Fico’s rhetoric. Constructive moderate speech can win lots of votes, as Caputova proved earlier this year.

Given Europe’s history with extreme nationalism, banning politicians from saying whatever they want on matters of race and ethnicity may look like an effective insurance policy against the emergence of another Hitler. It could be argued, though, that letting them speak their minds and play openly to nationalist sentiment would also strengthen resistance to populism. In a way, that’s what has happened in the U.S. since the election of Donald Trump as president.

Speech, even disgusting speech, shouldn’t be a crime unless it calls directly for violence. Fico should be allowed to fight on free of harassment. If he loses, it’ll be a sign that European values are alive in Slovakia. If he wins, it’ll be as clear a sign of more nationalist trouble in Eastern Europe — and a signal for moderate forces to organize more effectively.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Tobin Harshaw at tharshaw@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.