Silver Won’t Fall So Easily to the Memelords’ Assault

Speculative investors have managed to drive up the metal’s price before. The market looks very different this time around.

That suggests the retail investors who drove silver up as much as 7.5% late Sunday may have a harder time achieving anything like the gains they’ve notched in stock of GameStop Corp., which is up 1,625% so far this year thanks to an epic short squeeze.

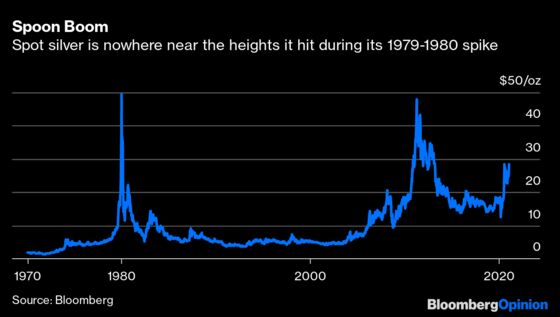

One reason for this is simply that short selling is a far more normal element of futures markets, as my Bloomberg News colleague Eddie van der Walt has argued. Still, that didn’t stop a notorious episode in 1979, when buccaneering Texan and Arab oilmen managed to cause a fivefold increase in the price of silver in a matter of months:

Indeed, in some ways, commodity markets have more appeal for people wanting to force prices to spike, as demonstrated by similar attempts over the years to corner markets in goods from copper and tin to rice, cocoa and onions. Pretty much the only people forced to buy shares at any price are short sellers attempting to cover their positions, but the ultimate consumers in commodity markets are all industrial users who have to continue buying to keep their businesses running.

Still, it’s the balance between those physical users and speculative players that determines the likelihood of a successful corner — and on that front, the silver market of 2021 couldn’t be more different than it was two generations ago.

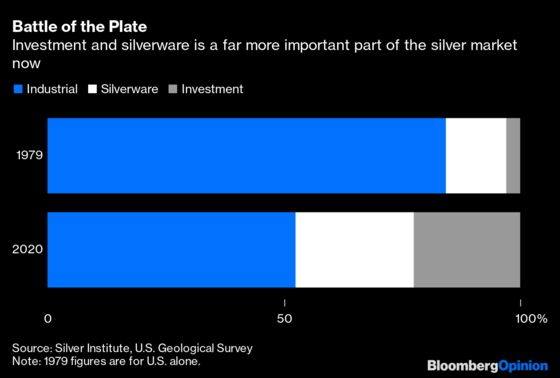

The most important factor is that industrial consumers are far less influential in terms of incremental demand. In 1979, about 84% of silver in the U.S. went into photographic emulsions, solders and electronics. Jewelry and cutlery accounted for about 13% and investment was a scanty 2.8% of the total.

That’s since changed drastically. Worldwide, those forced-buyer industrial users now account for barely more than half of the market, with the balance more or less equally split between silverware and investment bullion:

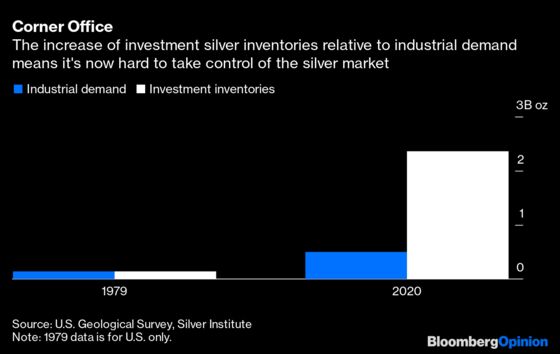

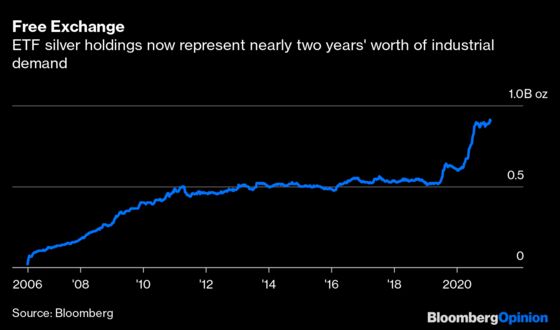

Next it’s worth considering how much silver is already stored away under lock and key. Thanks to the rise of financial products tied to commodities over the past decade, this is now a huge pile of metal — some 2.46 billion ounces, of which about 96% is investment-linked product. Only about 7.2% of that mountain is needed each year to meet the demand that's not being supplied by miners. As a result, there’s ample metal on hand in the world’s bank vaults that can be sold into any periodic price strength.

At the end of the 1970s, metal markets were still coming off the extended hangover of Alexander Hamilton’s 1792 decision to fix the dollar to the price of gold and silver. The selling down of the U.S. Treasury’s silver stocks in the 1960s depressed prices for the metal and discouraged mine production, so that much of the burgeoning demand for photographic film the following decade was met by recycling jewelry and coins rather than bringing new metal out of the ground.

That offered a tempting target for the sons of H.L. Hunt, a wildcat crude prospector who’d turned gambling winnings into one of the world’s biggest oil fortunes. (Members of the Hunt family have sometimes been suggested as the model for J.R. Ewing, the antihero of the 1980s soap opera “Dallas,” as well as the market-cornering Duke brothers in the 1983 film “Trading Places.”) By first purchasing more than 100 million ounces of silver and then buying exposure to at least the same amount again using futures, the Hunts and their associates made it almost impossible for industrial users to get hold of materials, driving the metal up to a still-record $49.50 in January 1980.

The balance of supply and demand these days won’t allow a repeat. U.S. inventories of investment silver in 1979 were unable to cover annual industrial demand. These days, global silver stocks could supply industrial use until 2026. Recycling of scrap silver, which accounted for more than a third of supply through much of the 1970s, these days amounts to about 17% of the total.

Exchange-traded funds alone now hold 905 million ounces, nearly double the 506 million ounces of annual industrial demand, and miners add another 800 million ounces or so every year.

That’s why you’re unlikely to see a sustained rise in the silver price. For all the market manipulation around the Hunt brothers’ 1979 silver market corner, that price run-up was driven by fundamental factors that are now absent. Memes won’t be enough to keep the current silver bubble inflated for long.

Better known by the acronym "YOLO,"one way of describing the devil-may-care attitude of posters on the WallStreetBets subreddit who've driven the surge in the price of GameStop Corp.

At least one smaller producer ended up doing just that: GAF Corp., a U.S. supplier of X-Ray paper, ended production of the film in 1980 and cut 500 jobs.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.