(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The British Business Bank, a government enterprise that aims to make “finance markets work better for smaller businesses,” this week urged domestic pension funds to invest more of the savings they oversee in unlisted companies. While the report has merit, its timing leaves a lot to be desired.

Investors are still trapped in Neil Woodford’s flagship fund after his efforts to juice returns by buying illiquid securities backfired earlier this year, forcing the well-known U.K. money manager to halt withdrawals. So it’s unfortunate that the study, commissioned by the government a year ago and co-authored by consultancy firm Oliver Wyman, is published just when regulators are scrutinizing whether to tighten the rules governing hard-to-trade investments.

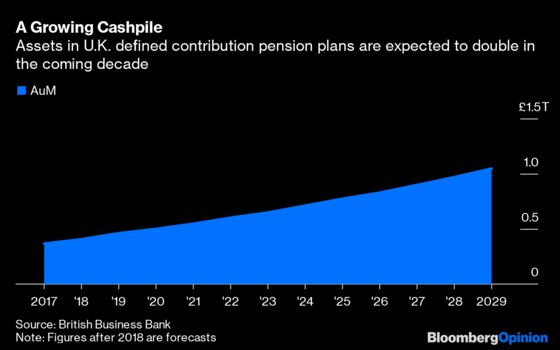

Small businesses in the U.K. raised 6.7 billion pounds ($8.2 billion) in equity finance in 2018, according to the BBB study. The plan aims to “unlock further investment” worth at least 20 billion pounds over a decade “for innovative firms.” To do that, the report proposes tapping a pool of U.K. assets called defined contribution pension schemes, which British employers have been obliged to offer to their workers since 2012. Those funds will more than double to surpass 1 trillion pounds in the coming decade.

The study, using data compiled by research firm Preqin, cites an average annualized net return for unlisted assets of 18% between 1970 and 2016, which beats the 11% delivered by MSCI World Index of global equities in that timeframe. Those superior returns, it argues, could mean someone starting work in their early 20s could end up boosting their retirement nest egg by as much as 12% by allocating just 5% of their savings to venture capital.

There are a couple of problems with that analysis. Past performance is no guide to future outcomes, as all fund managers are obliged to point out in their marketing literature. And as the study itself acknowledges, those investment return figures rely heavily on data from U.S. venture capital funds; “data is more limited for the U.K.”

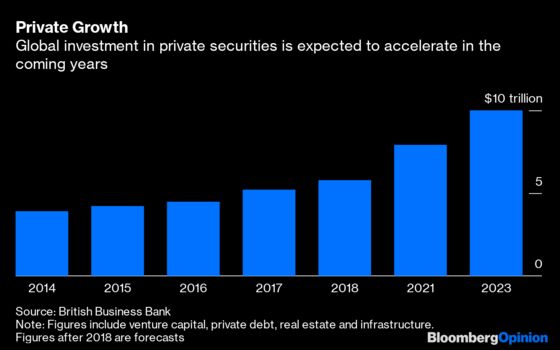

Moreover, there’s plenty of skepticism about how measurement snafus, such as benchmark issues, fee discrepancies and survivor bias, where performance measures exclude investments that were dropped along the way, inflate the alleged supremacy of private equity firms. And there are questions about how sustainable those returns are, given that the increase in funds allocated to private equities in recent years shows no signs of stopping.

The custodians of retirement savings certainly need to adapt to a world in which companies are increasingly shunning the public markets. The study says the number of publicly traded companies in the U.S. and U.K. has shrunk by 50% since 1996, with 500 British firms delisting in the decade to 2015. “Savers may miss out, while overseas institutions, family offices, and high net worth individuals profit,” the report cites the government as saying.

Woodford’s woes, though, illustrate the dangers involved in sacrificing liquidity to seek higher returns. I worry that U.K. savers are being invited to belatedly join a hoedown that’s already crowded with more sophisticated dancers, including sovereign wealth funds. The private equity party may be about to run out of punch.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Melissa Pozsgay at mpozsgay@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Mark Gilbert is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering asset management. He previously was the London bureau chief for Bloomberg News. He is also the author of "Complicit: How Greed and Collusion Made the Credit Crisis Unstoppable."

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.