Dropping Cambo Oil Field Won’t Help U.K. Carbon Cuts

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Climate activists claiming victory after Royal Dutch Shell Plc’s decision to drop development of the Cambo oil field may want to think again. It won’t significantly cut U.K. carbon emissions. Until serious steps are taken to reduce demand for fossil fuels, attempts to stop their production will simply cause shortages and move supply to other parts of the world.

Shell announced Friday that it was pulling out of a project to develop the field that lies beneath 1,100 meters of water some 80 miles northwest of the Shetland Islands. It is estimated by majority owners Siccar Point Energy Ltd. that the fields holds 800 million barrels of oil, of which between 240 million and 280 million barrels can be recovered. That’s enough to meet total U.K. oil demand for almost six months, but a fraction of the 3 billion barrels of oil equivalent pumped from the U.K.’s Brent field between 1976 and 2008.

Shell’s decision doesn’t necessarily mark the end of plans to develop Cambo. It says it will retain the stake and review the development in the future, although it is difficult to see the potential for delays — cited alongside economic reasons for Shell’s decision — easing any time soon. The project has become a rallying point for environmental campaigners and will be so again if it is revived. Legal challenges would inevitably follow any development approval.

So what is the impact of halting Cambo?

Certainly the loss to the U.K. of the highly skilled, highly paid employment associated with its development. Siccar Point put the number at “over 1,000 direct jobs as well as thousands more in the supply chain.”

Add to that a further reduction in U.K. energy security, as supply that could have come from domestic sources is pushed overseas, lengthening supply chains — with the environmental cost that imposes — and increasing dependence on foreign governments that may not always wish us well.

Of course, the energy security argument isn’t quite that straightforward. The U.K. is an integral part of a worldwide web of oil trade. As much as 85% of the crude produced in the U.K. in 2019 was exported, according to government figures. An even greater volume was imported, with almost half coming from Norway and another quarter from North America. In addition to crude oil, the U.K. also imported more than half of the oil products it consumed in the year before the Covid-19 pandemic struck.

And it’s not just oil trade that is global, so too is the climate crisis.

The climate benefits claimed by campaigners from not developing Cambo will, sadly, prove illusory.

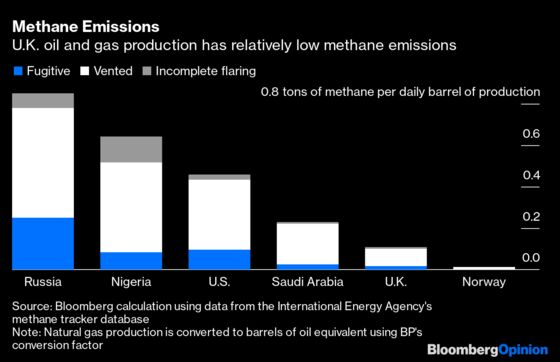

Shelving the project, as well as other potential oil and gas developments around Britain’s shores, will stop the direct emissions associated with their construction and operation. That may be good for U.K. emissions figures but will merely shift the problem overseas, very likely to countries where the greenhouse-gas footprint of oil production is much higher than it would have been for Cambo.

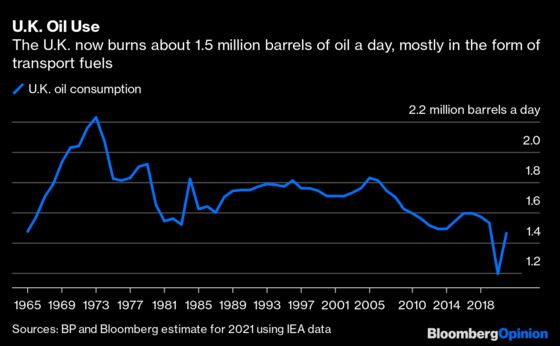

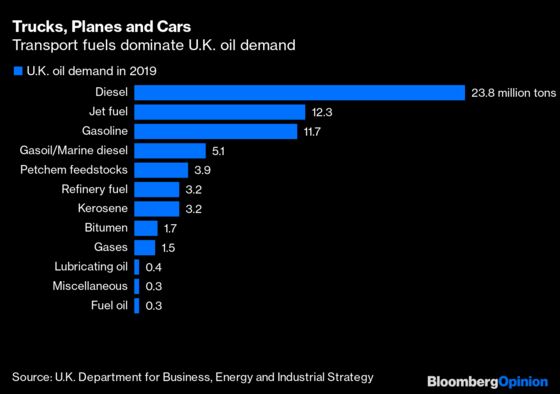

As long as Britons keep burning oil, with most of it used to power trucks, planes and private cars, somebody’s going to produce it.

I know oil companies make great, highly visible and very vulnerable, targets for campaigners — much less risky to mount a media campaign against Shell than to superglue yourself to a motorway — but the focus is wrong.

Tackling the climate crisis needs to start with the demand side of the energy balance. Until serious action is taken to address the concerns of would-be users of electric vehicles — range, cost, ease of charging — we will continue to consume vast quantities of gasoline and diesel. Without a concerted drive to insulate homes and switch heating away from natural gas, hydrocarbons will remain an integral part of the energy mix.

Shortage of gas supplies is already starting to bite, sending prices to record levels across Europe (including the U.K.) and triggering the collapse of more than 24 U.K. energy companies.

Oil shortages may follow. Analysts at JPMorgan forecast a doubling of oil prices over the next two years. Brent crude could hit $150 a barrel in 2025, as the world’s cushion of spare production capacity dwindles amid a lack of investment.

Environmental campaigners may relish a surge in oil prices — most of the population won’t.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Julian Lee is an oil strategist for Bloomberg. Previously he worked as a senior analyst at the Centre for Global Energy Studies.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.