Who’s Really Living in Oil’s La La Land?

Saudi Arabia calls IEA’s vision of the future unrealistic. It may want to reconsider its own vision first, writes Liam Denning.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Saudi Arabia’s energy minister, Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman, is a realist. This week, he compared the International Energy Agency’s recent net-zero emissions analysis to “La La Land.” Because a world in which the half-brother of an autocratic prince attempts to manipulate the price of a vital commodity in league with a clutch of other autocracies and struggling petrostates, even as that commodity stokes a climate disaster ... yes, that sounds totally normal and good.

The IEA’s “roadmap” is la-la land in the sense that it requires a “total transformation” of global energy. That is difficult precisely because, with the externalities of emissions largely unpriced, we rely heavily on an incumbent system predicated on “cheap” fossil fuels. But what then? The status quo means doubling down on climate change. That doesn’t sound particularly realistic; like “La La Land” except set in a noirish Los Angeles clouded by wildfire smoke.

Oil is incredibly useful, which is why it is deeply embedded in the modern economy and why its geopolitical compromises are tolerated. But now we know it also harbors dangerous externalities. To simply focus on the benefits and ignore the risks — especially for the emerging markets demanding more barrels — is irresponsible and ultimately self-defeating.

The IEA’s biggest bombshell was the contention that reaching net-zero emissions by 2050 meant no more investment in new fossil-fuel supply. That was never going to persuade the prince to treat it like a documentary. Remember, though, the IEA isn’t issuing orders; just making its best guess at what is needed to meet a modeled outcome.

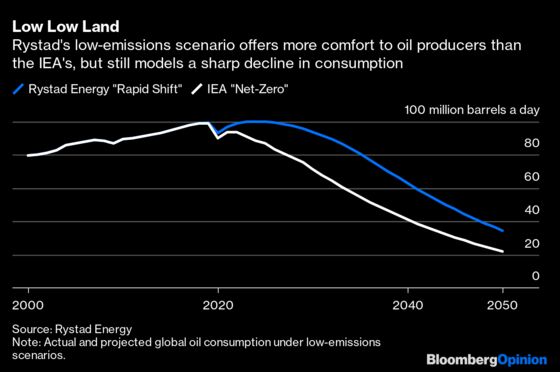

Oil demand is almost 23 million barrels a day higher in 2030 on Rystad’s projections compared with the IEA’s, a huge difference. However, it would still mean demand that year being roughly the same as in 2020 — not a great vintage. The oil market flips between fist-pumping and head-holding based on relatively tiny amounts. So Rystad’s scenario of consumption peaking in 2024 and then falling by 6 million barrels a day by the end of the decade — accelerating from there — still would represent epochal change.

Unlike the IEA, Rystad sees the need for an extra 10 million barrels a day from new fields. Even so, upstream investment drops below $300 billion by 2030, which isn’t too far from the IEA’s net-zero figures. Moreover, Rystad’s projection that annual investment in a transitioning energy system rises to levels last seen in the early 2010s suggests decarbonization is doable. It just means less of that spending goes into oil.

The point is that carbon constraints, across a range of scenarios, fundamentally alter the economics of the oil industry (and petrostates). The exact quantum aside, there is a world of difference between oil consumption that is actually growing versus being merely robust. Even if oil prices spike as restrained capex runs into resilient demand — a particular issue in the near term — that would also tend to reinforce the broader trend, as higher oil prices would encourage demand destruction.

This is why Saudi Arabia touts the low carbon intensity and cost of its oil. Besides being an implicit recognition that oil’s primacy is slipping, both claims are less compelling than advertised. Emissions from producing Saudi oil are indeed relatively low. But the vast majority of oil’s emissions result from using it, not pumping it. Factor that in, and the savings from swapping out even carbon-intensive Canadian barrels for Saudi ones are relatively small. This is why low-carbon scenarios lean heavily on changes in energy consumption, not just supply.

Similarly, Saudi oil is only low-cost if you ignore its role in supporting the country’s social contract. This explains OPEC+ efforts to maintain oil prices far above the marginal cost of supply. It’s also why the national oil company is reportedly ready to issue more bonds to fund its dividend even with Brent crude above $70.

If decarbonization is la-la land, what to call the idea of Saudi Arabia transitioning smoothly from a rentier model to a dynamic economy untethered to the oil price? Neom?

Rystad's projections imply global emissions falling to 7 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide-equivalent by 2050 (including carbon capture), not net-zero. Rystad characterizes this as being "closer to a 'Paris 1.6 degree'case", rather than 1.5 degrees Celsius.

For example, emissions per barrel of oil produced from Saudi Arabia's giant Ghawar field are estimated to be just one-sixth those of Canada’s Athabasca oil sands. TheCarnegie Oil-Climate Indexpegs Ghawar's upstream and full-cycle emissions at roughly 75 pounds and 1,085 pounds of carbon-dioxed equivalent per barrel and Athabasca's upgraded sweet synthetic crude oil at 454 pounds and 1,607 pounds. All told, burning a million barrels a day from Ghawar rather than Athabasca avoids about 0.25% of global annual emissions. All figures converted from metric equivalents. Comparison to global emissions as per 2019 data from BP's Statistical Review of World Energy.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.