Saudi Arabia and Russia Just Killed Optimism in Shale

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Something died in the oil market this weekend: hope. Or a certain kind of hope exemplified in the U.S. exploration and production business. This will be one of the enduring outcomes of the latest crash, even if — as some, you know, hope — Saudi Arabia’s declaration of a price war spurs a quick truce with Russia .

Unlike the crash of 2014 (or 2008), falling oil prices aren’t likely to spur an immediate rebound in demand. People aren’t holding off traveling today because jet fuel is too expensive.

In the financial markets, fewer will rush in to mop up all that blood on the floor. Investors did that before and, like the actions of OPEC+ over the past three years, they effectively provided a put for the E&P sector’s high-spending habits. This was exemplified, most obviously, in surging production growth and negative free cash flow. More importantly, it was embedded in a mindset of optimism, backed up by c-suite incentives built on visions of sunlit uplands ahead rather than the troublesome present (see this). Now, with energy valuations through the floor even before Saudi Arabia opened the taps, the equity and bond market put is gone.

Think of the damage this will inflict in terms of concentric circles. At the center are those companies that had optimism woven into their financial fabric. Occidental Petroleum Corp. is a prime example, having piled on debt and alienated shareholders to buy Anadarko Petroleum Corp. last year. It needed oil prices to stay up for at least a year or two to fund its strategy (which still included some growth) and get good prices on disposals. Despite repeated commitment to the dividend, it looks untenable, which is why the yield is almost 12%. Pre-market prices on Monday morning imply Oxy’s market cap will drop to less than $15 billion — about $8 billion lower than where Anadarko traded before bidding got underway less than a year ago.

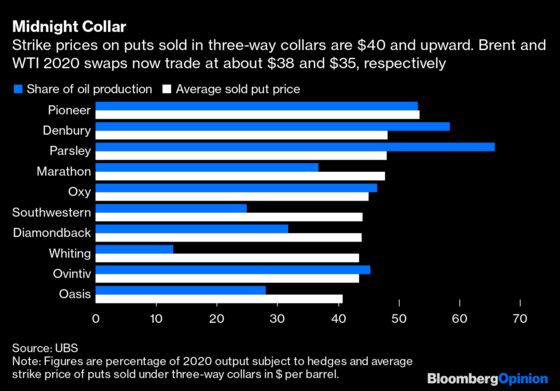

One way in which Oxy relied on the OPEC+ put to keep things humming was its hedging strategy. The company took advantage of oil’s brief rally at the end of 2019 to lock in hedges on almost half its expected production for this year. It looked like smart timing but came with a hope-tinged sting in the form of a three-way costless collar. The “costless” in there is the tell, like that subtle shift in the movie soundtrack when our hero opens the door to the cellar. In theory, by selling an out-of-the-money put on oil, the hedger’s premium reduces the cost of their calls and — cue the heavy bass notes — unless oil prices drop to a level nobody expects, it’s all good.

Oxy wasn’t alone in this regard, of course; the sector was conditioned to expect OPEC+ to do the decent thing. In a report published last week, UBS analysts laid out a list of large E&P firms that will now be grabbing at their collars frantically:

The impact doesn’t end there. Exxon Mobil Corp., usually a byword for stability, stuck to its guns on spending into oil-price weakness on Thursday — a day before OPEC+ redefined oil-price weakness. Rival Chevron Corp., having had the good fortune to take its licks a few years ago when hope still had currency, looks better positioned. But even its $60 oil-price planning deck is now in tatters.

The employees, and the towns and counties, that rely on drilling will also suffer. Direct oil-sector employment entered year-over-year decline already at the end of 2019, and that will now accelerate sharply. Similarly, the oilfield services sector, down already, will take another kick. Ditto for a midstream industry where, if anything, many companies had tried to out-do their E&P clients in terms of optimism, leverage and skewed incentives.

Radiating out further from ground zero in the shale patch, there are the financiers. Energy’s weighting in the S&P 500, having just slipped below that of utilities for the first time, may well drop lower than the real estate sector as soon as Monday.

Meanwhile, the energy high-yield bond market closed Friday at an average spread of almost 1,100 basis points above Treasuries. That is blowing out further Monday, meaning the door to new E&P financing, closed pretty firmly already, is now being welded shut. But like Vegas, what happens in energy high-yield doesn’t stay there, because earlier optimism allowed the sector to expand so much: Energy issuers constitute 14% of the face value of the broader high-yield index. You can’t detonate a part of the market that big and not expect a shock wave to hit the rest of it, especially with cross-currents from coronavirus rippling through, too.

At the same time, lending banks were already nervous about credit lines to E&P firms collateralized by the value of their oil and gas reserves. Mike Lister, who runs corporate banking for energy clients at J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. — one of the biggest reserves-based lenders on the street — said in an interview with World Oil published last week that banks wrote off more reserves-based shale loans last year than in any over the past three decades. On that front, the thing to keep in mind is that oil prices averaged about $60 a barrel in 2019, a level the industry would kill for right now.

The E&P sector’s relationship with the capital markets was shaky already, both because of prior excesses and a growing sense of dread related to climate change. That is precisely why some companies had embraced more shareholder-friendly measures such as governance reforms and bigger dividends. This sharp reminder that energy prices aren’t guaranteed at any level kicks away the last prop.

Shale isn’t dead, but with a swath of the industry about to go bankrupt or try to rationalize or consolidate its way through the crisis, its peculiarly robust brand of hope is. That is why, even if Moscow and Riyadh make up eventually, the effects will last. The financial ecosystem underpinning the shale boom will remember. Reluctant as I am to ever write these words, this time really is different.

On this, remember that Russia's oil companies pay their costs largely in a currency that floats, the ruble. The ruble crashed by 9% Monday morning. Moreover, Russia's system of oil taxation means its producers don't reap much from higher oil prices, as the state's take rises alongside them. As the Kremlin ponders its next step, one constituency whowon't be screaming for it to step back is the executives at its oil producers.See my colleague Julian Lee's take on the unlikelihood of a quick resolution here.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Mark Gongloff at mgongloff1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.