(Bloomberg Opinion) -- A wealth tax is a good idea. It attacks inequality directly while raising revenue for the government. It can be targeted toward the country’s wealthiest individuals while leaving the upper middle class alone. And by adding another layer of taxation, it can tax people who managed to avoid income taxes through clever accounting tricks or illegal evasion.

Democratic president candidate Senator Elizabeth Warren recently garnered attention for proposing a wealth tax of 2% a year on fortunes of more than $50 million, with an additional 1% surcharge for amounts over $1 billion. It was a bold, pioneering proposal — much larger than any of the similar taxes that European countries have experimented with (and mostly discarded) over the years.

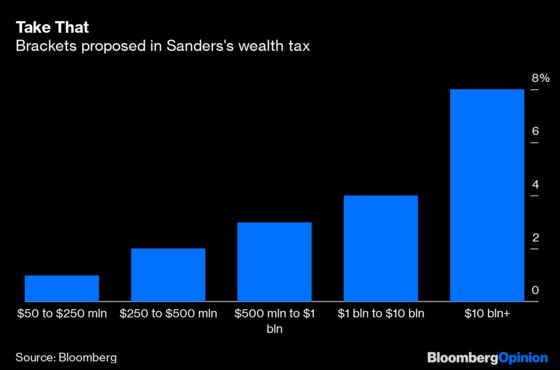

Now Senator Bernie Sanders, who also is seeking the Democratic nomination, has taken Warren’s proposal and simply dialed up the numbers. His tax would include five tiers:

If Warren’s proposal was unprecedented, Sanders’s is revolutionary. His top rate of 8% would be more than twice that of Spain’s wealth tax, which is the world’s highest, and many times that of Norway or Switzerland.

If the goal of wealth taxation is simply to shrink the number of very wealthy people in the U.S., then this is a good plan. Many rich people would move themselves or their fortunes out of the country — to Canada, Singapore, Switzerland, New Zealand or elsewhere — in order to avoid such a confiscatory level of taxation. Others would stay and pay the tax, and accept a much diminished level of affluence.

Sanders, true to populist form, obviously thinks that simply reducing the count of super-rich people in the U.S. is a worthy goal in and of itself:

But if the goal is raising revenue for government spending, the picture becomes a little more complicated. If rich people move themselves and their money out of the country, it deprives the government of the ability to tax their fortunes. Even if rich people stay, much of the reduction in their wealth will come not from actually paying the tax, but from decreases in the value of their assets, mainly financial holdings.

Wealth is measured by the value of assets — stocks, bonds, real estate and so on — that a person owns. But the value of those assets is determined in asset markets: If people are willing to pay $1,000 for a share of stock, that share of stock represents $1,000 of wealth. But if the owner paid $1,000 and price goes to $500, half of that wealth has simply vanished.

A wealth tax would substantially reduce how much people are willing to pay for stocks and other assets. Since a rich person who owns the asset would also have to pay the wealth tax, the value of the asset goes down, reducing the amount of money the government can raise. On top of that, owners of illiquid assets such as real estate will pay for those assets to be appraised at lower valuations to reduce their tax bills.

Another way to see this is to think of wealth in real terms rather than in terms of dollars. Wealth is represented by physical things that bring value to human life — houses people can live in, machinery that can be used to make things and so on. Unless Sanders manages to carry out a large-scale nationalization of land and industry — which could easily wreak havoc on the economy — most of that real physical wealth will remain in the hands of private individuals. Some will have to be sold to the non-super-rich at a discount in order to pay the wealth tax, and this would decrease inequality somewhat. But much would remain in the hands of the wealthy, who will hang onto their real assets and await the day that the tax is repealed or lowered, as happened in most of Europe.

In other words, wealth taxes are better at reducing inequality on paper than they are at redistributing real wealth. And this becomes more apparent as the taxes go from the modest levels that prevail in Switzerland or Norway to the confiscatory rates proposed by Sanders, and the wealthy resort to increasingly extreme tactics to preserve their fortunes. The difficulty of raising revenue via wealth taxation is the main reason most European countries abandoned the policy.

Very high wealth taxes could even hurt the broader economy. If wealthy people invest their money overseas, U.S. businesses could be starved of capital, creating an investment slowdown that would hurt American living standards. A Sanders administration might try to respond with large-scale nationalization of industry, but this would likely compound the problem.

Wealth taxes are a risky proposition. Even Warren’s tax, which is more than double Switzerland’s, was extremely ambitious; there was always the possibility that it would be too much and would have to be scaled back. Sanders’s tax, which is much higher than Warren’s, seems entirely outside the realm of prudent policy. Wealth taxes are good, but so are cake and ice cream. It’s easy to go overboard.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.