Russian Billionaire Gets a SPAC Reality Check Over Electric Buses

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- After raising roughly $12 billion in an initial public offering, Rivian Automotive Inc. now has a gargantuan war-chest to develop and build electric vehicles. Among its pricey ideas for how to use the money is a second U.S. factory that might cost $5 billion.

As long as that capital earns a decent return, it isn’t necessarily a problem: the 30% automotive gross margins Tesla reported recently are very encouraging. But is there another way that avoids having to spend so much money up front?

British electric vehicle manufacture Arrival SA thinks it can make do with far less by using proprietary composite materials (instead of metals) and building its vans and buses in what it calls “microfactories”: smaller facilities that use mobile, multitasking robots and that don’t require expensive paint shops or metal stamping.

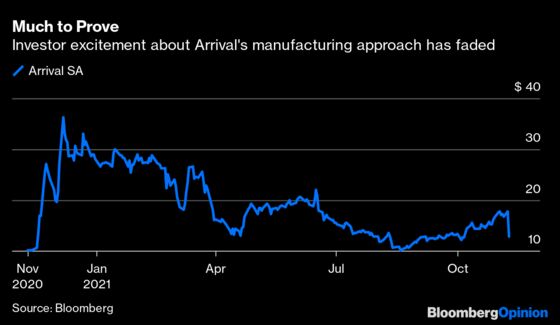

Its bid to demonstrate the auto industry’s capital-heavy approach is wrongheaded isn’t going entirely to plan, though. Arrival’s Nasdaq-listed shares tumbled more than 27% on Tuesday after it warned it will build fewer vehicles than planned when production commences next year; spending on things like tooling, logistics and raw materials will be higher than initially envisaged. Arrival is now valued at ‘just’ $8 billion.

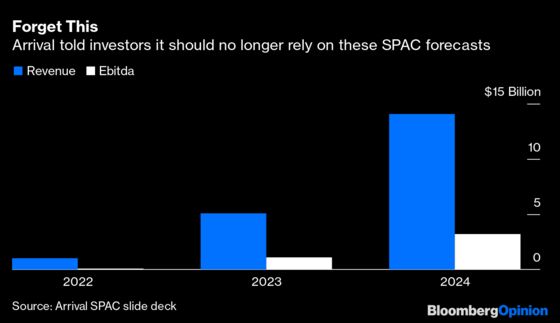

Arrival also scrapped the long term forecasts it published a year ago when it announced a merger with a blank-check firm CIIG Merger Corp, thereby joining a long list of SPAC-backed companies that have ditched their optimistic projections soon after going public.

In short: the promise of reforming the auto industry’s capital consumptive ways (Sergio Marchionne famously dubbed car giants “capital junkies”) remains just that — a promise.

Arrival isn’t alone among the recent crop of automotive startups taking a more capital-light approach. Fisker Inc. is also relatively thrifty, for example, because it plans to outsource production to partners Magna International Inc. and Foxconn Technology Group

But few manufacturers would dare argue the large-scale moving assembly lines pioneered by Henry Ford a century ago are old-hat. “We are doing things that have never been done before and expect our powerful technologies will change the fundamentals of the automotive industry,” Arrival’s billionaire Russian founder Denis Sverdlov told investors on this week’s call, somewhat immodestly.

Arrival plans to have three microfactories up and running next year — one in the U.K. and two in the U.S. — and from a financial perspective these have obvious appeal, at least in theory.

Costing around $50 million for 10,000 units of annual van capacity, microfactories should provide Arrival with much greater flexibility to quickly scale production to meet local demand. If one of its facilities has to halt or slow production for some reason, it will burn through much less cash compared to a stoppage in a large car factory.

Shareholders benefit, too, because less capital outlay means less potential dilution. Arrival’s SPAC deal generated a comparatively modest $610 million in net proceeds and hence Sverdlov still controls 75% of the shares.

However, investors won’t be sure the business model works until Arrival starts commercial production next year. As Tesla has discovered, an over-reliance on robots can cause more problems than it solves.

While it still has total faith in the approach, Arrival will now be more cautious in rolling it out: it will start out with only one work shift, rather than two, and construction of a fourth microfactory has been delayed until 2023. It’s also discovered there are some costs it can’t avoid. It’s had to spend more to secure battery supplies, for example.

The other unsettling bit of news was telling investors not to rely on the financial forecasts it published barely a year ago. In its SPAC merger prospectus, Arrival forecast $14 billion of annual sales by 2024 (it currently has zero) and Tesla-esque gross margins of 27%. I’ve written plenty on why the financial projections SPACs are allowed to publish (and companies going public the traditional way typically shy away from) are potentially hazardous.

If companies just abandon these goals soon after going public, that’s all the more reason for the U.S. to consider preventing them being disclosed in the first place.

Raising an enormous chunk of capital, as Rivian has done, is an easier way to accomplish what you promise. In contrast, Arrival’s microfactory approach remains untested. Besides revolutionizing manufacturing, it also now has to win back investors’ confidence.

VW's annual review of this budget is due in December

It expects to reach full capacity in 2023

Managmement added that any additional capital wouldn't necessarily have to come from the public markets.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies. He previously worked for the Financial Times.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.