Russia Oil Sanctions Don’t Have to Be a Blunt Instrument

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Ukraine’s prime minister, Denys Shmyhal, recently called payments for Russian energy “blood money,” underscoring the increasingly untenable moral position of the West. Leading global democracies express outrage over the atrocities committed by Russian forces in Ukraine but provide Moscow with hundreds of billions of dollars it can put toward its military efforts.

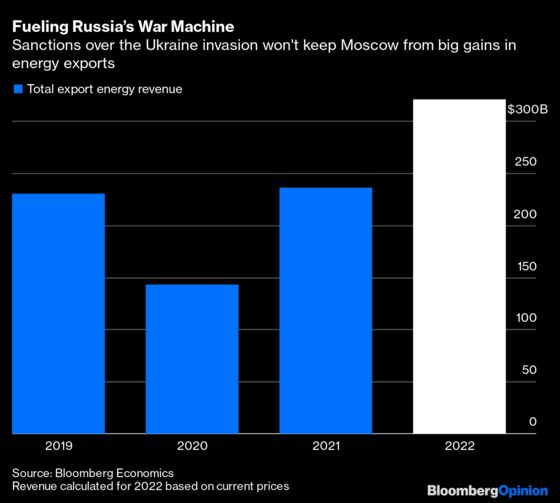

Bloomberg Economics estimates that, due to higher prices, Russia is on track to earn $320 billion from its energy sales in 2022, up more than a third from last year. This disconnect will become politically unsustainable, particularly given a prospective Russian offensive in eastern Ukraine likely to be jaw-dropping in its brutality.

Western policy makers are struggling with ways to punish Russia amid significant energy market uncertainty. For a way out of this dilemma, they should draw on policy innovations from a decade ago, designed largely in reaction to Iran’s nuclear pursuits.

The wave of sanctions against Moscow is still cresting. In response to Ukrainian entreaties, major oil-trading houses such as Vitol and Trafigura announced they will carry out existing contractual obligations, but not take on any new business related to Russian oil. Last week, the European Union and Japan agreed independently to ban the purchase of Russian coal.

The Debate Over Doing More

European officials have acknowledged they will continue to discuss further curtailment of Russian energy imports, although member states are divided about what costs to bear in their quest to increase pressure on President Vladimir Putin.

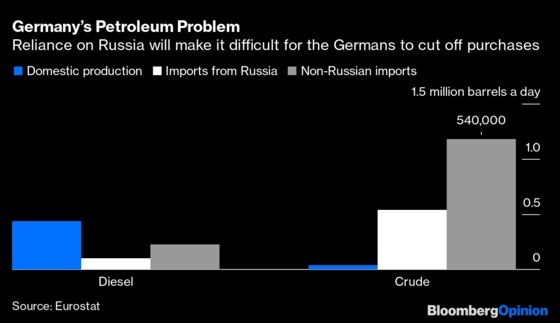

While most of the focus has been on European imports of natural gas, the purchase of Russian oil will be the next shoe to drop. Focusing on oil, while difficult, is easier and can have a greater impact than concentrating on gas.

Historically, Russia made $4 in oil export revenues for every $1 it made from selling natural gas abroad. (This ratio of oil/gas dollars dropped to 3-to-1 in 2021 because of extremely high natural gas prices.) Targeting oil sales is going for the Russian jugular.

Moreover, given that the market for oil is global and oil is a commodity easily shipped from one location to another, managing a European (but not global) ban on Russian oil sales should be less painful. At least in theory, Russian oil shunned by Europe could make its way to other markets, displacing that of non-Russian producers which would work its way to Europe, minimizing the pain at the pump.

For some, however, this fungibility of oil is a drawback rather than a virtue of a potential ban on European imports. India is aggressively purchasing Russian oil shunned by other buyers. In a virtual meeting this week, President Joe Biden reportedly counseled Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi not to increase India’s dependence on Russian energy.

In this view, the steep discounts offered by Russia to lubricate the sales mean that a European ban would somewhat reduce — but not staunch— revenue flows to Moscow. As a result, particularly if China were to buy more Russian oil, the main impact of a European ban would be to absolve EU countries from directly funding the war effort, rather than to cripple Russia financially.

For others, the main concern over a European ban on Moscow’s oil has to do with its consequences for the global economy, not with its impact on Russia. Europe now buys about half of Russia’s crude oil and petroleum products. An abrupt disruption of these flows could jolt energy markets, given uncertainty about how quickly, fully and seamlessly the oil market would rejigger oil-trade flows. Mohammed Barkindo, secretary general of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, told EU officials this week that “it would be nearly impossible to replace a loss of this magnitude” when speaking of a potential removal of Russian oil exports from the market.

The price of oil is now down from earlier spikes, mostly thanks to a huge release from the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve and from Covid-induced slowdowns in China’s economy, leading to revisions of China’s expected oil demand this year. But prices could shoot back up if more Russian oil comes off the market. The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies estimates that disrupting half of Russia’s oil exports, approximately the amount Europe purchases every day, could push oil prices to $160 per barrel by the summer.

Both these reservations about a future ban on Russian oil purchases are valid, but they will not annul a deep unease over continuing energy relationships with Russia as its forces assault eastern Ukraine.

Policy-Making in the Face of Uncertainty

Fortunately, there are more options than doing nothing or risking the state of the global economy. One, already embraced by Europe to some extent, is to declare a ban on imports of Russian energy that will phase in over the course of the coming months or the remainder of 2022. In addition to the new ban on coal, Germany says it may stop purchases of Russian oil by the end of the year.

Another option under consideration is creating an escrow account into which a portion of the proceeds of any sale of Russian oil will go, above some price viewed as sufficient to motivate continued Russian sales.

But such measures may seem insufficiently ambitious or too self-serving in the weeks ahead, putting pressure on political leaders to do more.

The U.S., too, will be urged to do more, even though the Biden administration already terminated American purchases of Russian energy. Members of Congress are speaking about “secondary sanctions” — penalties on third parties (such as corporations or banks) that continue transactions with Russia in a way that strengthens some specified element of the state. Energy purchases fall firmly into that category.

Uncertainty is always a challenge for policy makers, but in this instance the uncertainty is epic, particularly in the face of rising emotions over Russia’s atrocities and accusations of genocide.

When faced with future scenarios that are both plausible but widely divergent, good policy makers often ask whether there are tools or strategies that may prove useful if either situation materializes. This time should be no different.

Lessons From a Sanctions Superpower

American policy makers are fortunate that the U.S. is a sanctions superpower. This superlative applies not only in the sense that the U.S. uses sanctions more often and more aggressively than any other power. It has also experimented with sanctions, employing creative ideas in the past that serve as suggestions for the future.

Secondary sanctions have generally been associated with American overreach and allied outrage, as they are often seen as an example of the U.S. using its economic power when its diplomacy has failed to bring others on board. This need not be the case.

In fact, the secondary sanctions that have been used to dissuade non-American countries and companies from buying Iranian oil may offer some useful lessons for today. The sanctions incorporated into the National Defense Authorization Act in 2012 proposed a series of mechanisms that allowed policy makers to calibrate the pressure put on Iranian oil flows depending on the state of the market and political realities.

In 2012, Arab revolutions were sweeping the Middle East, and oil prices had been hovering near $100 for a couple of years. With the high prices and the world still moving out of the Great Recession, officials in President Barack Obama’s administration and elsewhere were reluctant to isolate Iran, one of the world’s largest suppliers of crude, from the global oil market without some significant safeguards.

The defense authorization law recognized this and required that the administration make periodic reports to Congress about the state of the oil market. And the president had to provide regular determinations whether oil markets were sufficiently supplied to continue with sanctions. (Given Saudi cooperation to stabilize oil markets and booming shale oil production in the U.S. at the time, the administration never needed to use the provision to pause sanctions.)

In addition, the NDAA created what became known as “significant reduction exemptions” from the sanctions. The Obama administration could employ these waivers for countries that had made progress in significantly reducing dependence on Iranian oil.

This package allowed the White House great discretion and led to exemptions for some of America’s treaty allies, such as Japan and South Korea, as well as for non-allies including China and India. The legislation also included the usual national-security waiver, which gives the executive branch the option to declare that suspending sanctions in a particular case would be in the national interest.

As pressure grows in Washington for more economic penalties on Russia, and for secondary sanctions in particular, Congress would be wise to consider these innovations from 2012. They could give the Biden administration the flexibility needed to diminish reliance on Russian energy.

Imagine, for instance, that Biden and Modi had discussed sanctions provisions like those used with Iran in the 2012 NDAA. Biden could have allayed any (legitimate) fears that tightening oil markets could spiral out of control, by assuring the prime minister that he had necessary tools to ratchet back any U.S. sanctions if oil markets seemed too tight.

Rather than giving Modi the stark choice between secondary sanctions or the full severing of India’s energy relationship with Russia, Biden could have elicited a more gradual and more realistic Indian move away from Russia.

Sanctions are often called a “blunt instrument.” They do not need to be.

More From Bloomberg Opinion:

-

Putin Has Fallen Victim to the Dictator’s Disease: Hal Brands

- Germany Must Wean Itself Off Russian Gas Sooner, Not Later: Chris Bryant

-

Ukraine War's Most Potent Weapon May Be a Cell Phone: James Stavridis

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Meghan L. O’Sullivan is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. She is a professor of international affairs at Harvard’s Kennedy School, the North American chair of the Trilateral Commission, and a member of the board of directors of the Council on Foreign Relations and the board of Raytheon Technologies Corp. She served on the National Security Council from 2004 to 2007.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.