(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Since opposition leader Alexey Navalny’s January arrest sparked anti-government demonstrations, the Kremlin has been ratcheting up efforts to silence disgruntled voices. A clampdown on social media, used to spread protest tips, news and footage, has ensued. Official rhetoric has become shrill, warning about Big Tech dominance and shrouding its tighter grip in moral terms, as a crusade to curtail the dangers of pornography and protect children.

On Wednesday, Moscow went one further, saying it would slow down Twitter, while threatening an outright ban over what it said was the U.S. firm’s failure to remove enough troublesome content.

What is arguably the most aggressive move to date has not, unfortunately for the Kremlin, been its most successful.

While some users reported that video and photo content was sluggish to load, some saw little difference. Other sites, including a handful of the government’s own, went down too. Officials blamed the outage on an unrelated equipment malfunction at top operator Rostelecom, but tech watchers and skeptical netizens suspect an embarrassing self-inflicted wound instead.

President Vladimir Putin has always had a tight grip on television — still a prime source of news for most of the country’s nearly 150 million residents — but until about a decade ago the Kremlin took a more laissez-faire attitude to the world wide web. That changed after mass protests in 2011 and 2012 over vote-rigging allegations and his return to the presidency for a third term.

New legislation quickly covered everything from mass digital surveillance to proxy services. Broad anti-extremism laws have been deployed liberally. A 2019 law set about creating a “sovereign” Russian internet, and forced service providers to install equipment that allows authorities to filter content and block it directly.

Yet so late in the tech revolution, silencing the digital version of Soviet samizdat is simpler in theory than in practice. By pushing opposition voices into the virtual space, Moscow inadvertently helped create internet stars like Navalny: Nearly 115 million viewers watched his film about an ostentatious seaside palace that Putin has denied having any link to. Russia has sued Google, Twitter Inc., Facebook Inc. and others, but activity continues.

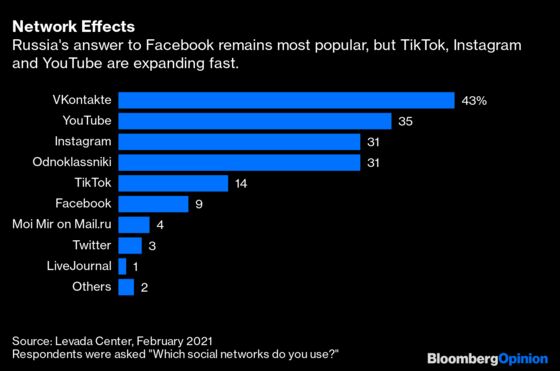

With more than 80% of the population online, it poses a real conundrum. Even hawks see potential in the digital economy, but of greater concern is the fact fewer Russians are listening to curated news broadcast by state channels, and more are shifting to foreign-owned social networks. While homegrown VKontakte remains a favorite, its slice of the market is becoming a little slimmer, according to pollsters Levada Center, and new arrivals are moving fast. Video app TikTok, a particular headache for the government, went from appealing to 2% of Russians in 2019 to 14% today, topping Facebook’s popularity.

Ever-tighter control is the new normal in a country going through the most repressive period in its post-Soviet history. Human Rights Watch has warned about the impact on freedom of expression and access to information.

Putting the brakes on Twitter has been both a test and a warning. Authorities picked an app used only by a fraction of Russians, and attempted to slow down only some content. But it’s no accident that they singled out a U.S. company for the first major test of whether mandated deep packet inspection technology really does amount to a kill-switch of sorts. Limited leverage with foreign companies — eager to be see defending online freedoms, as Twitter already has — means it’s crucial for censors to be able to act directly.

Russia has a poor record when it comes to muzzling individual platforms: It fought secure messaging app Telegram, but failed to curb it. The ultimate goal this time, says Irina Borogan, a fellow with the Center for European Policy Analysis and chronicler of security services activity, is less blanket silence or even to shut off Russia as a whole, but rather to use the technology to isolate problem cities, regions and to block specific content — especially the livestreaming of protests, which can go viral and incite more people to join. Hundreds of thousands participated virtually in recent anti-government marches.

But replicating in 2021 what China put in place in the 1990s with its Great Firewall is not just the technical challenge demonstrated on Wednesday. Beijing has fostered local social media alternatives that dominate at home. Russia has some, but is also reliant on outside favorites: The Foreign Ministry uses Facebook, and when the editor-in-chief of RT, formerly known as Russia Today, called for a ban of foreign social media companies, she did so on Twitter. RuTube has yet to catch up with its near-namesake.

That means curbs will be seen and felt, denting the image of a system that leans on perceived popular support. More go-slows and blockages will do little to help the economy.

In the run-up to legislative elections in September, crackdowns on specific critical content or livestreams of marches will increase. We also will see more officially approved YouTube and TikTok content, to rival videos by impudent anti-government teenagers and Navalny’s campaign.

Most worrying, heightened pressure means those efforts will be paired with low-tech methods of silencing virtual critics: Arrests for activists, bloggers — and even those simply retweeting their views.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Clara Ferreira Marques is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities and environmental, social and governance issues. Previously, she was an associate editor for Reuters Breakingviews, and editor and correspondent for Reuters in Singapore, India, the U.K., Italy and Russia.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.