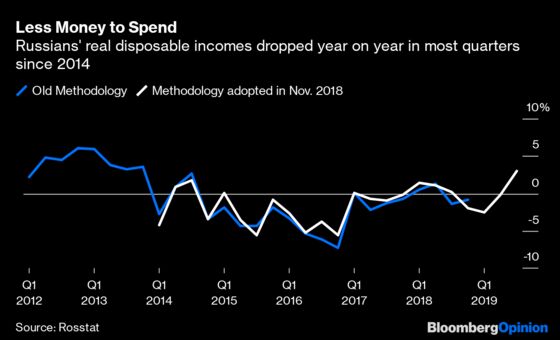

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Russian’s have reason to celebrate, at least according to data published by the national statistics office last week. Their real disposable incomes grew 3% year-on-year in the third quarter, the most since 2013.

The problem is, it’s unclear exactly where the improvement comes from.

Russian President Vladimir Putin appears to be obsessed with real incomes. It’s a statistic he mentions more frequently than economic growth. Sometimes he argues, as he did in June, that incomes are pulling out of their dive. Sometimes he expresses concern, as he did in August, that they’re not growing. Sometimes he tells the government, as he did last month, that economic growth is only desirable if citizens’ incomes also grow.

It’s understandable that Putin’s worried. Before 2014, his unspoken contract with Russians was more prosperity in exchange for less freedom. The patriotic fever following the Crimea annexation tided Putin over as falling oil prices and sanctions hit the Russian economy. But now that enthusiasm has faded, and Putin fears that popular dissatisfaction could lead to mass protests. When incomes decline, that probability grows.

That means last week’s report from the Rosstat statistics agency was particularly good news for Putin. It’s a headline number he can proudly cite as proof that his policy of boosting government spending on so-called “national projects” is already having a beneficial effect on ordinary Russians.

Independent economists, however, struggled to understand where the unexpectedly big increase might have come from. Central Bank data indicated that the value of loans issued to individuals had been increasing, which would imply downward pressure on disposable incomes from interest payments. Retail sales have been slowing down. And real wages weren’t growing fast enough for such an increase in July and August. Unfortunately, no one knows what wages did in September because Rosstat, contrary to previous practice, didn’t publish those data along with the real disposable income number. “But wages are a key component of incomes,” Kirill Tremasov, formerly head of the Economics Ministry’s forecasting department, wrote on his Telegram channel. “If Rosstat has no September estimate for wages, how did it calculate incomes? It seems to me Rosstat is continuing to undermine trust in statistics.”

That’s a shame because Pavel Malkov, Rosstat’s current chief who was appointed last December, has said his goal is to strengthen the quality of data collection and analysis. What’s been more noticeable so far are the stronger numbers.

To address the outstanding questions, Rosstat came out with an explanation: Apart from the “low 2018 base,” the other major reason for the recorded growth in incomes was an increase in “gray” wages — that is, those paid in cash to avoid taxation. In the first quarter of this year, such unofficial payments made up just 7.8% of Russians’ incomes, but they reached 14.1% in the third quarter, according to the statistics agency.

This explanation would imply that Russia’s shadow economy is growing. But Rosstat’s own data show that it has been declining steadily relative to Russia’s economic output in recent years, to 12.7% of gross domestic product in 2018 from 13.8% in 2014. There is no reason to expect that Russia’s ever-tightening tax controls have slackened considerably this year. In any case, data on shadow incomes are especially hard to check.

Such aggressive accounting is a potential headache for economists who use official Russian data for analysis and forecasts. And it doesn’t change the major challenges the government faces in improving standards of living.

Rosstat has just released fresh survey data showing how Russians estimate their living standards. In the second quarter of 2019, the share of households that report only having enough money for food and clothes increased to 49.4% from 48.8% a year earlier, though the share of even poorer people, who can only afford food, dropped to 14.1% from 16.1%.

Taken together, these numbers mean almost two thirds of Russians are barely making ends meet and have no way to save. According the edition of Credit Suisse’s Global Wealth Report, a Russian adult’s median wealth amounts to $3,683 compared with $65,904 in the U.S. Russia stands out as the major economy with the most inequality of all. There, the wealthiest accrue some 58% of the country’s wealth, compared to 35% in the U.S.

This is a reality that can hardly be glossed over with upbeat statistical reports. Putin’s chances of holding on to power beyond the end of his current term in 2024 or passing it to a chosen successor increasingly depend on his ability to suppress protest, as the Kremlin did last summer in the run up to the Moscow city council election in which opposition candidates weren’t allowed to run. A tangible improvement in living standards is proving more difficult to deliver than nicer statistics.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Melissa Pozsgay at mpozsgay@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.