When it comes to the energy transition, Russia is like Wile E. Coyote: suspended in mid-air. Reassured by today’s prices and all too aware that tinkering with hydrocarbon production carries political risk, Moscow has pushed back inevitable change. It has obfuscated climate conversations and dismissed the idea of a wholesale shift to a greener future as a Western conceit. Unfortunately, as the plunging Looney Tunes cartoon canine knows, it’s a strategy that can only work for so long.

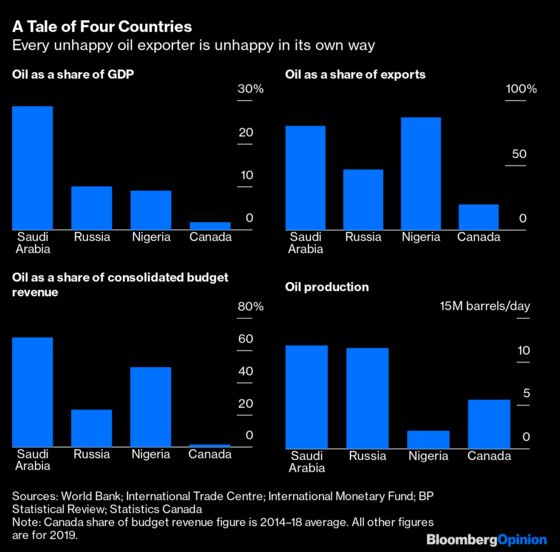

Our ability to manage the shift into a climate-friendly era will require hydrocarbon-dependent nations to get on board — and there is arguably no country on earth whose move away from carbon-spewing fuels matters more than Russia’s. Not just because the largest nation on the map is already suffering more than most from a warming climate, and doing far too little to help mitigate the damage. It is the world’s biggest exporter of the dirty stuff: Saudi Arabia may compete for the top spot in oil, but Moscow is also a leading gas exporter and No. 3 in coal sales. Failing to manage the shift brings political and economic risks, inside Russia’s borders and beyond.

There’s plenty of green promise, including in renewable energy: Yury Melnikov, senior analyst at the Skolkovo Energy Centre, estimates the technical potential for wind power alone could add up to 17,000 terawatt-hours, several orders of magnitude from today. Russia has the potential to become a major producer of blue hydrogen, if the world’s largest gas reserves are combined with investment in carbon capture technology, making the process cleaner. It already has plenty of low-carbon nuclear and hydropower generation.

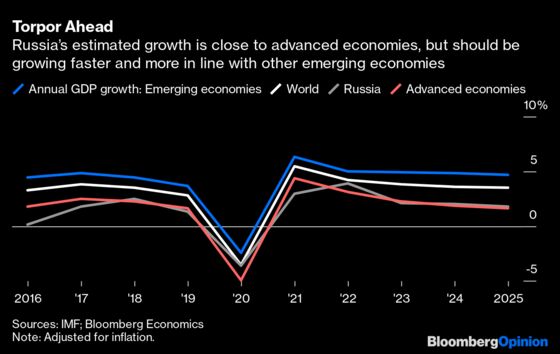

The problem is not a lack of opportunity. Rather, it is the rising opportunity cost of tinkering around the edges while trying to keep the system unaltered. Moscow is betting on sustained fossil fuel demand from emerging markets and what it sees as the competitive advantage of large oil and gas reserves, while ignoring increasingly loud alarm bells. Europe, a key export market, is pushing for a green-tinged recovery and implementing a carbon border tax, while China could see oil demand peak in 2025 and the U.S. will be very different under new management. The single-minded focus isn’t helping to shake the Russian economy from its torpor, ever more uncompetitive, while real disposable incomes and consumer confidence languish.

Russia may well be facing what Indra Overland at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs calls its Kodak moment, after the photography company that failed to see the importance of digital, underestimated change underway, and went bankrupt. Survival instincts should be kicking in. Instead, Moscow is making only token efforts to diversify, hanging on to hydrocarbon rents and overestimating the role of gas — which emits less carbon dioxide than oil or coal — as a transition fuel.

The Kremlin has been slow to recognize an impending shake-up before, as with the rise of U.S. shale. The problem today is that other factors are blurring the picture further.

First, good macroeconomic management and fiscal prudence, which have helped cushion the impact of sharp and swift oil drops, as in 2020, now mask the need for action — a “competence resource curse,” as Overland described it to me. Russia’s increasingly isolated position and confrontational diplomacy is also making matters worse. The siege mentality visible during the crisis over the poisoning and jailing of opposition leader Alexey Navalny is hardly conducive to self-examination, let alone a climate and energy rethink. Finally, crude prices holding around $60 a barrel thanks to supply cuts, well clear of the level Russia needs to balance its budget, are providing a false sense of security and an illusion of lasting demand.

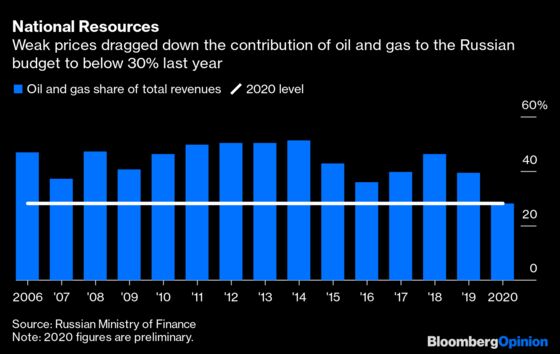

It’s true that oil and gas revenues accounted for just over a quarter of the total budget last year, down from an average of over 40% in the decade before. But that’s less a reflection of diversification, as the government argues, than it is about weaker oil prices, and a dependence that is increasingly hidden on the expenditure side of the ledger, in subsidies and indirect support.

In fact, it’s hard to overstate the addiction. This isn’t just a country that produces and exports fossil fuels. Oil, gas and coal are tied into the state at every level, employ and service towns, support elites, and define Russia’s view of itself, as well as its position in the world. It’s behind much of the inequality gap, too, as resources are sucked up by large firms and imperfectly redistributed.

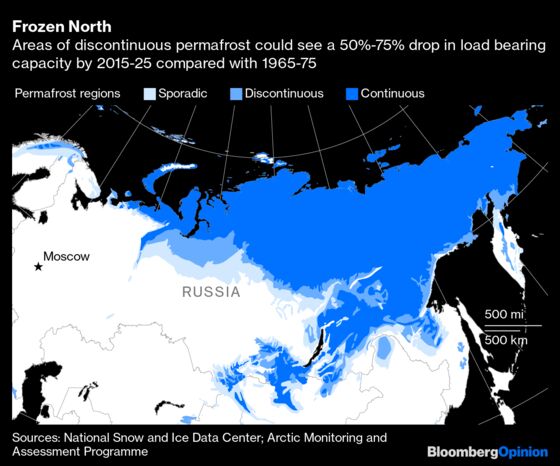

None of this is changing fast enough. In fact, the larger and more complex the projects required to keep Russia producing, the more significant the role of the largest state-owned enterprises, entrenching their dominance and that of hydrocarbons, as Richard Connolly at consultancy Eastern Advisory Group points out. The flagship Vostok Oil project, which is estimated to require an investment of more than 10 trillion rubles, or just over $130 billion, and includes 15 new industry towns, is run by heavyweight Rosneft Oil Co PJSC. It has also roped in shipyards, state nuclear company Rosatom and many more. A Bloomberg report last month found infrastructure projects linked to the venture were high on the list of candidates that could be supported by billions from the state wealth fund.

Frugal support for small businesses during the pandemic has done little to ease that grip.

Autocratic regimes are by nature inflexible. Yet even fewer officials will be incentivized to experiment at a time when a political transition is on the horizon: Vladimir Putin can stand again in 2024 when his fourth term as president ends, but has begun to put in place additional options for his future. It doesn’t help that inside oil and gas companies, executives are usually older, male and with little experience outside the country. There are no loud shareholders demanding a BP Plc-style overhaul, or press for policy action — not even BP itself, which owns 20% of Rosneft.

Russia’s Energy Strategy to 2035, published last year, is a good example of the challenges at hand. It talks up innovation and efficiency, but continues to prioritize the sale of hydrocarbons (albeit predicting a greater role for gas), and to put climate last. There is an effort to diversify target markets, but exports are expected to increase.

That’s despite rising oil extraction costs as fields age. It leaves Russia in a far more precarious position than, say, Saudi Arabia, if oil prices weaken and remain weak. In 2017, the energy minister put the cost of production in the Arctic offshore at between $70 to $100, levels oil is unlikely to stay at for long. Russia risks becoming the world’s “carbon haven,” as climate adviser Ruslan Edelgeriev put it earlier this year.

There’s one glimmer of hope, and that’s pressure from export markets. It’s the one factor that may just trigger an epiphany.

Indeed, it’s already prompting louder talk of the potential for clean hydrogen, particularly from Gazprom PJSC, independent gas producer Novatek PJSC and Rosatom. A development plan approved by the government last year is vague, but a helpful signal. For renewables, distant hamlets are beginning to turn to wind and solar to tackle the cost and security risk of diesel deliveries: Skolkovo’s Melnikov points to the Arctic settlement of Tiksi. Meanwhile, miners like MMC Norilsk Nickel PJSC, the largest producer of high-grade nickel, a key battery ingredient, are talking up appetite for their minerals. Russia has copper, rare earths and more, too.

There are even policy discussions on how to tackle the shift to low-carbon supply chains globally.

It’s all still too tentative. This year there are actually plans to cut back funding for renewable energy, to keep a lid on electricity prices.

Energy transitions will produce a more heterogenous world. Is Russia prepared for what happens when, if analyst Mikhail Krutikhin is correct, the country ceases to be a net oil exporter by 2035? It’s hard to answer anything but no.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Clara Ferreira Marques is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities and environmental, social and governance issues. Previously, she was an associate editor for Reuters Breakingviews, and editor and correspondent for Reuters in Singapore, India, the U.K., Italy and Russia.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.