Russia’s 30-Year Vision Is Realized With Nord Stream 2

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline linking Russia to Germany beneath the Baltic Sea is vilified in the U.S. and parts of Europe as a Russian plot to ensnare European gas buyers. It’s not. It’s the final link in a 30-year project to divert Russian oil and gas exports away from transit routes across former Soviet neighbors. From a Russian perspective, that’s a perfectly logical goal. If you don’t think so, just ask the Canadians about Keystone XL.

Ever since the Soviet Union broke apart in 1991, Russia has been faced with the problem of being dependent on pipelines running across countries that were suddenly independent, and not necessarily friendly, to transport almost all of its oil and gas to international markets.

It couldn’t even deliver crude to its major Black Sea port of Novorossiysk without pumping it across a corner of Ukraine, while its major Baltic Sea outlet was in Latvia. Gas deliveries to western Europe had to cross one or more of the former Soviet republics of Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova. They then had to pass through at least one of the former satellite states of Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Romania and Bulgaria.

Moscow’s relations with all of those countries were changing — and not for the better from Russia’s point of view.

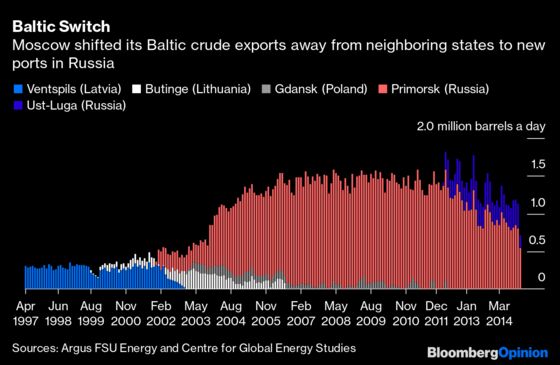

So Moscow began a series of projects to cut its reliance on transit across former Soviet states for hydrocarbon exports. New oil export terminals were built on its Baltic Sea coast. Once the first of those — at Primorsk — was completed, export flows through ports in Latvia, Lithuania and Poland dwindled to nothing. All of Russia’s rising overseas oil shipments were eventually sent through Russian ports.

The same thing happened in the south, with crude flows through the Ukrainian terminals at Odessa and nearby Pivdenne halted by the end of 2010.

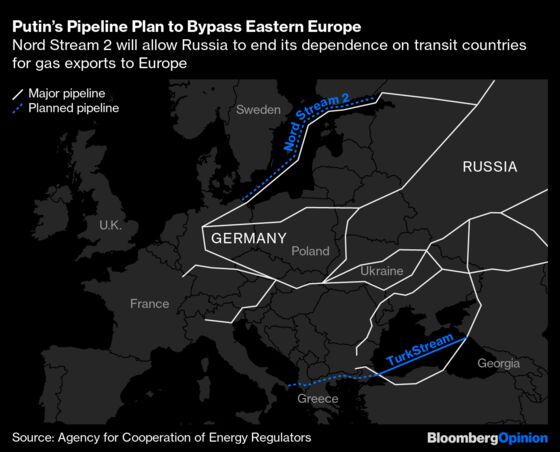

Russia undertook a similar process with gas. Big new export pipelines were built to link Russia directly to major customers — first Turkey and then Germany. The Blue Stream pipeline beneath the Black Sea reduced Russia’s dependence on transit across Ukraine to deliver gas to Turkey, while Nord Stream reduced the roles of Belarus and Poland in deliveries of Russian gas to Germany and other buyers in western Europe.

Those routes were followed later by Turk Stream and now Nord Stream 2.

Russia’s policy shouldn’t come as a surprise, nor is it unique.

The history of transit pipelines isn’t a happy one. The list of those that have fallen out of use includes the IPSA pipeline that linked oil fields in southern Iraq to Saudi Arabia’s East-West pipeline and the kingdom’s own Tapline, which carried its crude to an export terminal on Lebanon’s coast.

Others have been proposed, planned and even partly built, only to end up on the scrap heap. Construction of the TAPI pipeline, intended to carry gas from Turkmenistan across Afghanistan and Pakistan to India, has been discussed for at least 25 years, but looks even less likely to get built now than it did in 1996.

The fate of the Keystone XL pipeline, intended to deliver Canadian crude to refineries and export terminals in the U.S., should serve as a warning to all who consider relying on transit across a neighboring country to get their hydrocarbons to market.

Even the transit pipelines that have survived, and thrived, have often not served their initial owners as well as planned.

Russia used its own leverage as a transit country to change the management and taxation structures of Kazakhstan’s CPC pipeline to its advantage. Turkey has done similarly as the host of oil and gas pipelines from Iraq and Azerbaijan, extracting both higher transit fees and greater control.

It’s no surprise, then, that Russia has sought to end its reliance on similar links.

Russia’s gas export monopoly, Gazprom, has a deal to continue shipping its gas via Ukraine, but that only runs until 2024. Nord Stream 2 will soon displace, not supplement, existing gas flows through Belarus, Poland and Ukraine, finally bringing an end to Russia’s dependence on former Soviet and satellite states for transporting oil and gas to western export markets.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Julian Lee is an oil strategist for Bloomberg. Previously he worked as a senior analyst at the Centre for Global Energy Studies.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.