(Bloomberg Opinion) -- To say it’s absurd that an electric-truck maker that hasn’t yet delivered any trucks to regular customers should seek an $80 billion valuation is to state the obvious.

That isn’t a knock on Rivian Automotive Inc., which announced Friday that it has filed for an IPO confidentially. From what we can tell, it seems like the real deal. It’s just a common-sense observation about cash flow and multiples and the inherent difficulty of building vehicles at scale. And yet, in 2021, it feels almost churlish to point this out.

A big reason for that is Tesla Inc. Like some giant celestial body, its $700 billion-plus market value has warped the fabric of market space-time, demonstrating that it’s possible to garner a mind-boggling valuation on the back of minimal profits and expectations of future businesses that are either barely there or simply don’t exist.

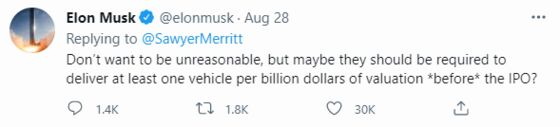

So when Tesla CEO Elon Musk tweets ...

… he’s not expecting that to actually be taken seriously, right?

In any case, the rumored Rivian number and Musk’s reaction to it says a lot about where the auto sector sits today. The potentially massive electric-vehicle market is still up for grabs and, rightly or not, clean-sheet upstarts are prized more highly by investors to win that fight than gasoline-based incumbents. However high a valuation venture capital is willing to buy in at, recent history suggests there’s a strong likelihood public market investors will be willing to pay more. Rivian, for example, raised private funds only a few months ago at a valuation of $27.6 billion — a lofty level then that seems quaint now.

For a fortunate few, then — Tesla, Lucid Group Inc. and Rivian among them — the car industry’s famously voracious appetite for capital consumption is no longer a significant barrier. The “capital junkies,” to use the late Sergio Marchionne’s barbed turn of phrase, have arrived at their bacchanal.

Even though there’s plenty of money available to start a car company, actually making money at it without a hiccup remains as difficult as ever. Rivian is coming to the public markets with almost impossibly high expectations and faces intensifying competition. An $80 billion valuation would be a ticket to raising yet more cheap funding but doesn’t provide much room for manufacturing or sales disappointments.

The IPO prospectus isn’t available yet, but Rivian’s current financials can’t be pretty. Ignoring conventional wisdom about learning to crawl before you walk, it’s trying to launch three vehicles almost simultaneously: a pickup, SUV and commercial delivery van. These are potentially lucrative segments, but the size of its ambition magnifies the potential for production setbacks and cash burn.

Customer pre-orders and a contract to supply 100,000 delivery vans to its investor Amazon.com Inc. ensures there will soon be some money coming in the door. However, rather than outsource production to save money, Rivian has acquired and retooled a former Mitsubishi plant in Illinois and is already scouting for further sites. It has also developed a lot of technology in house. This helps explain why Rivian has already raised $10.5 billion since 2019 from a cast of creditable investors such as Amazon, Ford Motor Co., T. Rowe Price and BlackRock, even before getting to the IPO.

Ford’s backing underscores the chasm that exists between incumbents and challengers. Earlier this year, the Detroit automaker outlined its own plans to electrify its core products — which overlap rather neatly with Rivian’s lineup. Yet for all its experience and relationships with customers and suppliers, not to mention more than 5 million in annual vehicle sales (in a normal year), Ford is valued at just $53 billion. At least on paper, Ford has already earned a stunning return on its Rivian investment — it booked a $900 million gain in the first quarter — but it has also helped seed a more richly valued competitor.

Sentiment toward the old-school automakers has improved lately even as some of the fizz has come off the neophyte EV developers. For example, electric pickup truck maker Lordstown Motors Corp. has warned it could run out of money trying to start commercial production. That’s one problem Rivian doesn’t face yet, but it has already had to push back first deliveries for truck and SUV customers by several months because of various teething troubles, including around component supply.

Musk has spoken vividly about his own “production hell” and probably feels he endured more than his share of hardships before Tesla earned its stratospheric valuation. Even so, all told, Tesla has delivered fewer than 2 million vehicles since the start of 2010, and it’s valued at 13 times Ford’s market cap. Analysts compete to justify these numbers with ever more expansive business models. In one notable recent example, this involved putting robots on Mars, inspired by Musk’s own claims of developing a Tesla-bot while a person dressed as a robot cavorted on stage. It’s a bit rich to pull a stunt like that and then suddenly get all Jim Chanos about Rivian’s truck ambitions.

The climate crisis requires the urgent deployment of vast sums to retool entire industries. At least in the auto world, investors seem happy to supply it, albeit mainly to companies that aren’t hauling combustion engines on the journey. Whether that’s fair is a valid question; certainly, the new crowd’s valuations don’t bear any relation to financial fundamentals. In any case, no one can blame Rivian for making the most of it — least of all the man who already has.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies. He previously worked for the Financial Times.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.