Rising Mortgage Rates Are Starting to Become a Problem

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- One of the pillars of the U.S. economic recovery during the Covid-19 pandemic is starting to crack.

The red-hot U.S. housing market, fueled by record-low interest rates, is one of the the most important stories of the past year when it comes to understanding the sharp rebound in financial markets and the relatively pristine condition of many household balance sheets. The Freddie Mac 30-year fixed mortgage rate started 2020 at 3.72%, just 40 basis points above its all-time low, and plunged to 2.65% by the start of this year. That drop in borrowing costs led to all sorts of astounding figures: The largest quarterly volume of mortgage originations in history; the most refinancing in a year since 2003; the most debt taken on by first-time buyers on record; and a collective $182 billion of home equity withdrawn during 2020, or an average of about $27,000 for each household.

These trends are quickly shifting just a few months into 2021. U.S. mortgage rates have increased for six consecutive weeks, to 3.17%, the highest level since June. The 50-day moving average was steady at 2.94% in the week through March 25, the first time it hasn’t moved lower since early 2019. Other longer-term averages have also plateaued. The message is clear: The absolute low for U.S. mortgage rates appears squarely in the rear-view mirror.

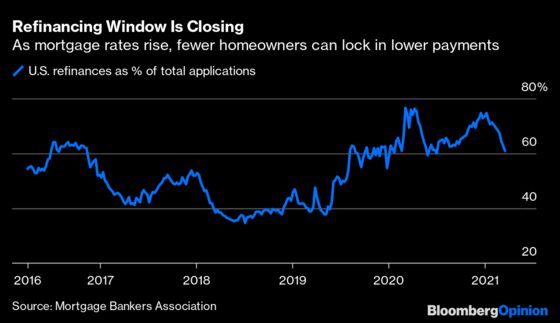

Not surprisingly, this trend has squashed the refinancing demand that prevailed throughout 2020. Refinances as a percentage of total mortgage applications have declined for seven consecutive weeks to 60.9%, the lowest since July, in a streak that rivals the longest of the past decade and will probably only continue. The days may also be numbered for cash-out refinancing, which is when someone not only cuts the interest rate on their loan but also increases the size of their new mortgage by borrowing against equity in the house. The $152.7 billion created through this practice last year was the most in dollar terms since 2007. My Bloomberg Opinion colleague Alexis Leondis recently argued that this carries much less risk than in the lead-up to the housing bubble 14 years ago, but that might not be enough reassurance to attract those who haven’t already sought a cash-out refi over the past several months.

If that were the end of the story, the outlook wouldn’t be so murky. After all, it was such an active 2020 in the mortgage market that a breather seems only natural. However, by all accounts U.S. housing demand still remains solid heading into what is historically a strong seasonal period. Even though new and existing home sales tumbled in February and missed estimates, both figures remain at levels that prior to the pandemic hadn’t been seen since the mid-2000s bubble. Meanwhile, housing starts have dropped from what was the fastest pace since September 2006.

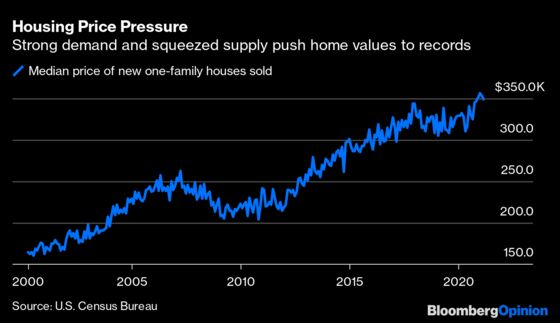

This creates all the necessary conditions for bidding wars. According to Redfin, only 645,000 residential homes are for sale in the U.S., down almost 50% from a year ago and the fewest in at least five years. As a result, 36.1% of homes have sold above their list price, again the largest share since at least early 2016. Only a sliver of houses have had to come down in price because on average buyers are happy to meet sellers right at their asking level, which is rare. It’s little wonder that the S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price Index reached a record high in December, increasing 10.4% from a year earlier. January’s data is officially released Tuesday — CoreLogic suggests another double-digit annual increase is in the cards.

Rock-bottom mortgage rates certainly helped take the sting out of surging home prices in recent months. An increase of 50 basis points from a record low might not seem like much, especially when the prevailing 30-year rate is still well below any historical average. But it’s bound to sting when layered on top of much higher house prices and when potential homeowners are increasingly expected to bid above the listing price, stretching the upper limits of their target range.

Here’s what the math looks like. The median price for a new one-family house sold in the U.S. reached a record high $356,600 at the end of last year, according to the Census Bureau. At the prevailing 30-year mortgage rate of 2.65%, that comes out to a $9,450 annual payment. In January 2019, when the median dropped to a two-year low of $305,400 but average mortgage rates were 4.46%, the yearly cost was about $13,620. Now, with home prices at $349,400 but rates jumping to 3.17%, annual payments total $11,076.

Of course, early 2019 marked the peak of the Federal Reserve’s monetary-policy tightening, and longer-term Treasury yields remain well below where they were two years ago. But Chair Jerome Powell and his colleagues are content to let the yield curve steepen. A 2% yield on benchmark 10-year Treasuries by the end of the year, from 1.6% currently, is increasingly becoming the consensus view on Wall Street. A parallel 40-basis-point increase in mortgage rates, with median home prices constant, would mean an extra $3,000 in annual payments compared with the end of 2020.

Perhaps a few thousand dollars in additional interest pales in comparison to Americans’ war chest of excess savings, estimated at $1.7 trillion from the start of the pandemic through January by Bloomberg Economics. It’s also certainly possible that homebuilders will rise to the occasion and increase housing supply, or that demand could cool as city centers reopen and renters no longer feel the need to pay up to own property in the suburbs.

Regardless, the housing market doesn’t look as if it will offer the same boost to the U.S. economy and financial assets as it did over the past year, when Americans locked in savings through refinancing or scored a record-low rate on their first home, or at least felt the “wealth effect” of their existing property increasing in value. After 12 months of living with a pandemic, the country might be ready to stand on its own without the support of record-low borrowing costs. But if it wobbles, look to mortgage rates as a likely culprit.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.