(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Rishi Sunak, Britain’s chancellor of the exchequer, delivered another steroidal burst of government spending on Wednesday. As the man writing fat checks at a time of disruption and uncertainty, Sunak has become so popular that it’s now obligatory to include the words “potential future prime minister” whenever his name is mentioned. He enjoys a 92% approval rating among Conservative Party members, which is more what you’d expect in Belarus than in Britain’s rough-and-tumble political world.

He has a pedigree to rival any other front-rank Tory. His platinum-plated CV includes stops at Oxford University, Stanford and Goldman Sachs. The son of immigrants, he’s married to the daughter of a billionaire. A policy wonk in sharply tailored suits, he also has an encyclopaedic knowledge of Star Wars trivia and is considered a nice guy. He’s exhibited both the right temperament for the moment (unflappable, focused, collegial) and a flair for the fiscal splurge that is unconstrained by his previous hawkish orthodoxies.

“We entered this crisis unencumbered by dogma and we will continue in this spirit,” he said on Wednesday.

Yet winning acclaim for chucking cash at anyone who asks for it is the easy part. At some point, possibly around the time of the autumn budget, people will want to know how he means to pay for his largess. Boris Johnson’s Conservatives can sound almost identical to Keir Starmer’s Labour Party in their determination to protect working people’s interests, but will that remain the case if Sunak wants to hike taxes at some point?

His slew of spending pledges is a bet that the government can put a floor under the economic damage done by the coronavirus, without creating structural deficits that burden future generations or fostering a dependency culture that Conservatives deplore. Sunak is trying to soothe Tory fears by presenting his blowout as a series of time-limited targeted interventions.

Naturally enough, his immediate priority is jobs. Britain’s furlough scheme, which props up 9 million jobs, is due to do be wound down from August, when employers will have to shoulder more of the burden. That’s expected to result in a great shedding of jobs, particularly in sectors such as hospitality and travel.

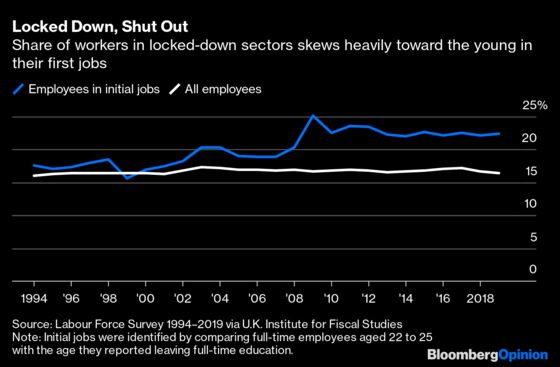

Wednesday’s “summer economic update” included as much as 30 billion pounds ($38 billion) of new spending, on top of the previous 160 billion pounds of direct support for the Covid-hit economy and 123 billion pounds of subsidized state loans and deferred taxes. It was directed especially at younger people, who are disproportionately affected by the shutdowns:

The beleaguered hospitality industry, which accounts for about 10% of total employment, gets special support. Value-added tax for the sector was cut to 5% from 20% and Brits have even been given government-funded discounts to dine out Monday through Wednesday. There was also a nod to the problem of getting furloughed staff back to work: Across the economy, employers who bring these workers back onto the payroll will receive a 1,000-pound bonus.

While Sunak says Britain has implemented one of the most generous pandemic responses in the world, its fiscal interventions were equivalent to about 4.8% of GDP before Wednesday’s announcement, according to the Bruegel think tank, putting it behind Germany and the U.S. and on a par with France.

Still, a different stripe of Tory government might have accepted the inevitability of widescale unemployment, as President Donald Trump has in the U.S., and used fiscal policy to provide welfare relief. Sunak insists that his policies are driven by values, not economics.

Sunakism — if indeed this is a pitch for future power — claims to have at its core the sanctity and nobility of work. “I will never accept unemployment as an unavoidable outcome,” he told Parliament on Wednesday. At the same time, the chancellor doesn’t want to “leave people trapped in a job that can only exist because of a government subsidy.” His policies are predicated on the idea that government can protect some jobs and stimulate the creation of others, while supporting those who fall through the cracks.

But these are largely blunt instruments. For example, many people are avoiding restaurants for safety reasons, and others may find it hard to get a table. A VAT cut doesn't solve either problem.

At each turn, Sunak has been careful to underscore the extraordinary nature of the circumstances. Like the furlough scheme, all of the other new measures are meant to be temporary and have an immediate effect. But few people who get a steroid injection stop after just one. When so many people are dependent on the state for their livelihoods, there is powerful pressure to maintain the flows of cash.

Given the blow to the economy, some of the forecasts on joblessness post-Covid are dire, and Johnson has promised to look after those former Labour voters who delivered him victory in December’s general election. It won’t be easy to turn off the taps.

The Sunak approach raises three important questions. First, will his carefully targeted measures limit the Covid damage and revive the British economy? Second, how will they be paid for? And third, what are the long-term consequences for Britain’s political landscape and the shape of its economy?

For now, only the first question matters. Sunak has put off the financing conundrum until the autumn budget. It’s hard to see how some tax increases can be avoided, although this is a government that has committed itself to reducing the tax burden where it thinks that might stimulate the economy.

As for the third question, a new doctrine of conservatism appears to be emerging that accepts the state as a prime actor during a crisis but tries to avoid the perils of chronic French-style interventionism. Sunak has called on the British people to have the “patience to lie with the uncertainty of the moment” so they could find “a new balance between safety and normality.” That balance may be more elusive than he thinks.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Therese Raphael is a columnist for Bloomberg Opinion. She was editorial page editor of the Wall Street Journal Europe.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.