EV Batteries Won’t Be Enough to Save the Mining Industry

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Rio Tinto Group’s decision to push the button on a project in Serbia to produce lithium for electric vehicle batteries is a sign of how the mining industry is working to embrace the transition to net-zero emissions. It’s also emblematic of just how difficult that transition is going to be.

The company said Tuesday it will commit $2.4 billion to the Jadar project, which will produce lithium carbonate as well as boric acid, a material used in cockroach poison and high-strength magnets, with an aim to produce 58,000 metric tons of lithium a year starting in 2026.

Lithium is undoubtedly a boom market. Demand will increase from around 400,000 tons last year to around 2 million in 2030 as electric cars start to take over from gasoline, according to BloombergNEF. While right now the metal costs about half its 2017 peak, it’s likely that demand will start outstripping supply just as Jadar is getting up and running. That would pressure prices and drive up miners’ revenues even faster than the fivefold increase in volume.

The trouble is, that still represents a drop in the ocean. Even at 2017’s record prices, a 58,000 ton-a-year lithium business will struggle to crack $1.5 billion in revenue, and Rio Tinto turns over more than $45 billion every 12 months. Normal year-to-year fluctuations in the price of iron ore are more than enough to overwhelm whatever impact Jadar makes to the bottom line.

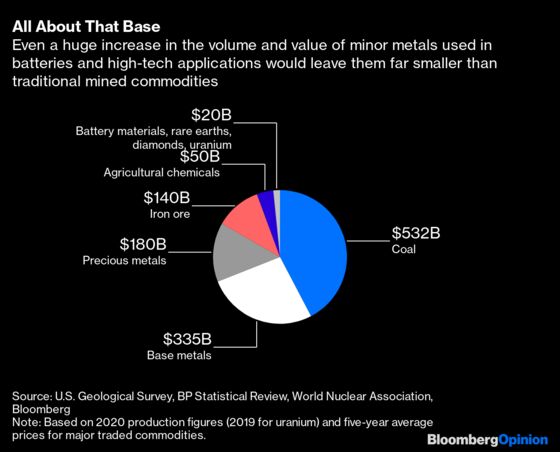

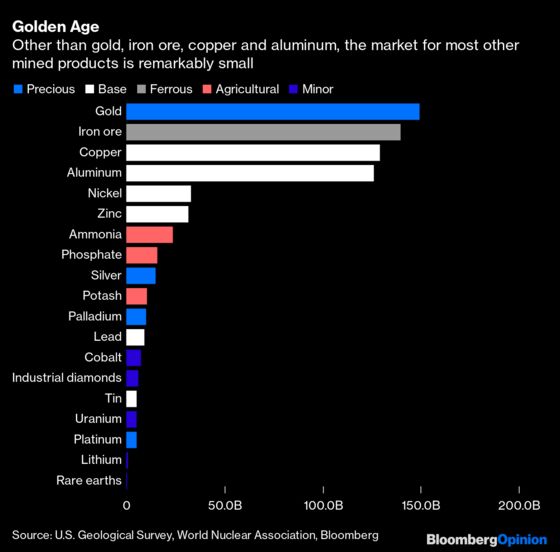

That’s the same across an array of materials. Crude oil alone accounts for more than half the value of mineral-resource extraction globally; add natural gas and you’re close to two-thirds, and coal takes you to nearly 80%. Gold, iron ore, copper and aluminum account for another 4% or so each. Everything else put together comprises the final 4% or 5%.

That represents the most serious challenge for the mining industry in the years ahead. For much of the past two decades, they’ve been running on so-called bulks — easily extracted, low-value, large-volume commodities such as iron ore and coal. While all the big miners except Glencore Plc have now pulled out or are in the process of pulling out of coal, they’re still deeply dependent on iron ore, with that commodity alone accounting for nearly 82% of Rio Tinto’s net earnings in the six months through June.

That party won’t go on forever. China’s voracious appetite for steel is close to being sated. Within five years or so, the amount in use will hit the levels seen in rich countries, where demand for fresh iron ore falls off as the industry turns to recycling scrap instead. Achieving such a transition is one major objective of its latest five-year plan, and recycling scrap would have the additional benefit of sharply reducing emissions. Unless India then produces an industrial boom on the scale of China’s, iron ore consumption may be close to its peak.

For all the excitement around the exotic cornucopia of minerals that will be needed to decarbonize our economy, hardly any of them account for enough volume and value to move the needle for major miners. All the world’s lithium, cobalt, rare earths, industrial diamonds and uranium put together earn less revenue than Rio Tinto gets from just its Australian iron ore mines.

No wonder that mining companies are spending such vast sums on copper and aluminum — the two nonferrous metals with the scale and price to measure up to iron ore, gold and fossil fuels. It's little surprise, either, that BHP Group and Anglo American Plc have been making forays into agricultural chemicals such as potash: Unlike metals, fertilizers can’t be recycled.

The risk of a shift toward steel recycling is a harbinger of those changes. A world that’s using energy more thriftily will also be more parsimonious with its mined commodities and recycle more of its scrap, because most of the energy consumed in making metals comes from physically grinding up ore and breaking chemical bonds in refineries.

Some parts of the mining industry already operate on this basis. The majority of the world’s lead isn’t dug out of the ground, but recovered from flat auto batteries and processed to be used again. Sales of gold and silver by central banks in excess of mine supply have caused some of the biggest disruptions those markets have seen over the past 50 years.

There’s always going to be a need to dig more metals out of the ground, thanks to the challenges of sourcing, sorting and separating scrap and refining it to the quality that industrial users need. Still, a world in which the majority of countries have industrialized and are moving toward a services economy is going to look very different than the one in which mining companies have grown rich.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.