(Bloomberg Opinion) -- If there’s a party happening in global finance, you can usually rely on Hong Kong to turn up late, just as the champagne is going flat and the last of the guests are straggling away. With the air having come out of the SPAC craze a while ago, the city is inevitably ready to get in on the act. It’s a bad idea.

A word about special purpose acquisition companies, to give them their full title. These are companies with no assets or operations, which raise money through an initial public offering with the objective of buying another business that will then take over the listing. Investors in such ventures are essentially betting on the skill of the SPAC promoter to identify and execute a profitable deal. To put it another way, shareholders don’t know what they’re getting into (though they have the option to redeem their investment if they don’t like the resulting transaction). It’s a blind bet.

If this sounds familiar, it should. Every history of financial manias worth its salt has a chapter on the South Sea Bubble, during which one company sought funds “for carrying out an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is.” For generations of finance students, this apocryphal tale has stood as a droll monument to the gullibility of investors caught up in the judgment-sapping enthusiasm of a stock frenzy. Three centuries later, the SPAC boom has institutionalized it as a routine element of the investing landscape. Who’s laughing now?

For Hong Kong, the hazards of introducing such an innovation are particularly salient. The city’s stock market has a long history of abuse involving shell companies and reverse takeovers, which regulators have spent years trying to control. That, you might think, hardly argues for the creation of a new, officially sanctioned class of shell company whose only purpose in life will be to carry out a reverse takeover (when a private company gains a listing by merging with a publicly traded one).

To get a taste of what a Hong Kong SPAC dawn may bring, cast your mind back to the first internet bubble. The entrepreneur class was relatively slow to wake up to what was happening on the other side of the Pacific, but jumped on the bandwagon with avidity once it realized the riches on offer. Notable cases included Richard Li’s Pacific Century CyberWorks, which listed in 1999 via a reverse takeover that saw the target’s shares rise 20-fold, and which then bought Hong Kong Telecom, a former monopoly that was a staple of mom-and-pop investors. Now known as PCCW Ltd., the stock’s cumulative return (including reinvested dividends) in the 21 years since its high is minus 87%, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Or there is New World Cyberbase, born from a reverse takeover of a small construction company. Now called Mongolia Energy Corp., this has the distinction of not one but two bubble incarnations, having pivoted to the resources boom in 2007. The stock’s total return since its December 1999 high is a cool minus 99.96%.

Bear in mind that there was nothing illegal in these cases, which involved companies started by a scion of Li Ka-shing, Hong Kong’s richest man for much of the past few decades, and the Cheng family’s New World Development Co. — both pillars of the city’s business establishment. There are many less salubrious examples from this frenetic period, when every day seemed to bring another dowdy widget maker or apartment seller discovering its inner dot-com and renaming itself for a future of tech glory (and dilutive share issues).

The point is that Hong Kong’s stock market is full of nimble corporate operators with an eye for the main chance. When the market is in effect saying, “Here, take some money, you can decide what to do with it later,” they are most likely to say: “Yes, please.” When and if things turn south, outside shareholders are usually the ones left nursing the losses. While shell manipulation can happen anywhere, Hong Kong lacks the class action lawsuits that enable investors to seek redress in markets such as the U.S., as the Asian Corporate Governance Association noted in opposing the SPAC proposal last week.

The city’s exchange operator, which ended its consultation on Oct. 31, is well aware of these risks, and is proposing multiple safeguards for its SPAC regime. That’s a little like installing a giant flamethrower in the middle of a wooden village, then surrounding it with protective screens and signs saying “Warning: Fire Risk.” It’s all well and good, but… why put it there in the first place?

That’s a rhetorical question, obviously. As long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance, as the former Citigroup Inc. Chief Executive Officer Chuck Prince once said. The U.S. has done it, the U.K. is doing it, and — most importantly — regional financial rival Singapore is doing it, too. In the past three years, 12 companies from greater China and Southeast Asia listed in the U.S. via SPAC transactions, the exchange’s consultation document notes. The Hong Kong government wants a piece of the action, so there’s little doubt it will happen.

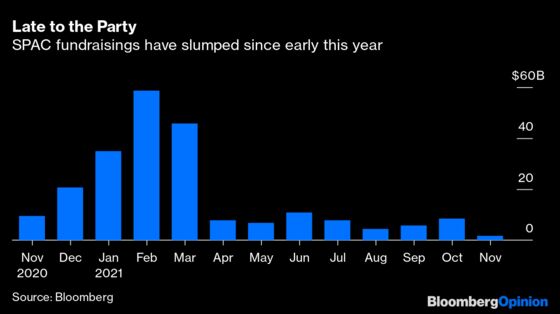

Whether the music really is still playing is debatable, though. SPAC fundraisings have slumped since April amid increased regulatory scrutiny in the U.S. (though the fervor aroused by a blank-check vehicle linked to Donald Trump suggests a revival is possible). The best hope for Hong Kong might be that this boom dies of its own accord.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Matthew Brooker is a columnist and editor with Bloomberg Opinion. He previously was a columnist, editor and bureau chief for Bloomberg News. Before joining Bloomberg, he worked for the South China Morning Post. He is a CFA charterholder.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.