A Model Economy Stops Drinking Its Own Kool-Aid

Australia is moving closer to embracing what was once unthinkable: the crisis tool of quantitative easing.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Australia is edging closer to needing a dose of extra stimulus if it’s to retain its status as the magical land where recessions don’t happen.

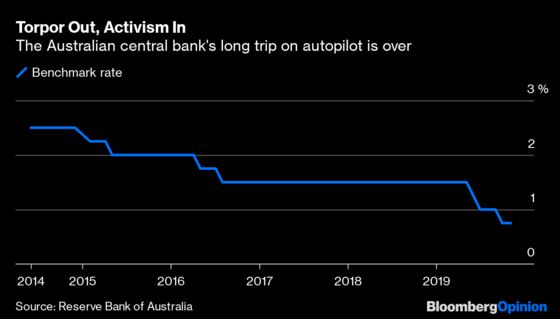

That juice may take the form of quantitative easing — a once-unthinkable step for a country with a historical preference for budget surpluses and an economy that’s expanded continuously for 28 years. After four quarters of slowing growth and three rate cuts since June, the central bank is signaling its openness to unconventional monetary measures.

Any doubt about the urgency of the economic situation ought to be banished by the publication this week of minutes from the Reserve Bank of Australia’s Nov. 5 meeting. Governor Philip Lowe considered cutting interest rates for a fourth time this year. That would have been a shock; none of the economists polled by Bloomberg predicted a reduction.

Such a move would have been even more jarring considering that the RBA met on the day of the Melbourne Cup, Australia’s equivalent of the Kentucky Derby. The event is dubbed the “race that stops a nation,” as many market participants decamp to bars or the track.

Absent an emergency, central banks are loath to surprise investors. That policymakers even considered this one indicates how seriously Lowe takes the substandard state of Australia’s economy, where growth cooled to 1.4% in the second quarter from a year earlier. The RBA deserves kudos for including the discussion in the minutes. Central banks consider closely what to include and what to leave out of such documents, so the contents become strategic decisions.

One reason the RBA refrained from another rate cut is that, with the benchmark at 0.75%, the central bank is already bumping up against the limits of effectiveness of conventional monetary easing. This passage points implicitly to the need to consider other options as the economy continues to weaken:

“While members judged that lower interest rates were supporting the economy through the usual transmission channels (including a lower exchange rate, higher asset prices and higher cash flows for borrowers), they recognised the negative effects of lower interest rates on savers and confidence. They also discussed the possibility that a further reduction in interest rates could have a different effect on confidence than in the past, when interest rates were at higher levels.”

QE involves the purchase of bonds by central banks to depress market interest rates when official benchmark rates are close to zero. It was deployed most famously by the U.S. Federal Reserve in the global financial crisis and its aftermath, and is alive and well in the euro zone and Japan. Australia is a very different kind of beast. This would be a deployment outside the northern hemisphere in a country without a significant manufacturing base.

In effect, the RBA has put the Kool-Aid away on Australia’s economic miracle. QE is contentious there because, for so long, people thought the place was special — possessed of a combination of luck, geography and policy that produced unending growth. QE is more commonly associated with economies in crisis. Yet the adoption of such tools is looking increasingly likely early in 2020.

Should he proceed, Lowe will at least have a reservoir of goodwill on his side. The RBA is almost revered in a way that applies to few local institutions. That's in large part due to Australia’s decades of prosperity.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison could help by administering a large jolt of debt-financed fiscal stimulus. Canberra can borrow for 10 years at little more than 1%, so money is cheap and a delayed return to surplus wouldn’t be the end of the world. In theory, such a move would also increase the supply of sovereign bonds available for the central bank to buy in any QE operation.

With rural Australia suffering from devastating drought and searing bushfires, the case for meaningful fiscal action has rarely been clearer. The RBA is signaling readiness to do its part. It shouldn’t have to act alone.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Daniel Moss is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian economies. Previously he was executive editor of Bloomberg News for global economics, and has led teams in Asia, Europe and North America.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.